The Log House

Like the broader project of Craftsman Farms itself, the Log House evolved over time with three documented concepts published in The Craftsman from 1908-11. If the siting and aesthetics changed throughout that period, the spiritual and symbolic significance of the building did not: it remains today–as it always has been–the very center of the campus from which all other endeavors radiated. When the family moved to the property in 1910, it was felt not through its presence, but its absence: a spate of land that was designated for the building and which throughout their initial months they probably witnessed the clearing and preparation of. From The Craftsman's House to the Club House to the Log House as we experience it today, the evolution of the building is intimately tied to Stickley's understanding and experience of the property, and of this broader project called "Craftsman Farms" that he was creating.

Renderings, plans, and sections of the Craftsman's House from the October 1908 issue of The Craftsman.

Published in the October 1908 issue of The Craftsman, the plans and drawings for "The Craftsman's House" read, in hindsight, as a kind of dream home Stickley had long been working on, but one not necessarily well suited to the goals of the broader campus. It was by far the largest of the three iterations of the central building, consisting of six bedrooms, two sun porches, a billiard room, a work room for Stickley, as well as indoor and outdoor dining areas. If the Log House today is marked by a sense of simplicity, then the Craftsman's House can only be described as extravagant, with custom-designed stained glass featuring his motto in the living room and two pergolas on the exterior. For the exterior of the house, Stickley planned large tinted plaster panels, set between the timbers that would announce to visitors the work undertaken at the property:

In each one of the large panels, picture tiles will be set, symbolizing the different farm and village industries ;-for example, one will show the blacksmith at his forge, another a woman spinning flax, others will depict the sower, the plowman and such typical figures of farm life. These tiles will be very dull and rough in finish, colored with dark reds, greens, blues, dull yellows and other colors that harmonize with the tints of wood and rocks. The figures will be simply done, so that the effect is impressionistic rather than definite.

The article featured renderings of the interiors, plans of all three floors, and even cross-sections of the walls that would demonstrate to readers the methods used in construction. It was, as the title noted, "a practical application of all the theories of home building advocated in this magazine." Despite these claims–and the enormous amount of expense and effort that must have gone into creating these plans and sections–this whole idea was quickly abandoned, and by December 1908 a different vision for the property's center had emerged.

Illustrations from "The Club House at Craftsman Farms: A Log House Planned Especially for the Entertainment of Guests," published in the December 1908 issue of The Craftsman.

There was a certain urgency in the December 1908 issue of The Craftsman as Stickley announced that "the first necessity at Craftsman Farms will be the club house, or general assembly house, planned in such a way that meals may be served either indoors or out... and where meetings, lectures, and entertainments of all kinds may be held by people staying at the Farms and accomodation provided for guests invited from the outside." Work on the building, readers were assured, "will be started early in spring." In reality, nothing was further from the truth. There were no visitors to the Farms, no places for people to stay, and it would be another 18 months before the the cottages that Stickley and his family lived in were habitable. One senses that once the idea had been planted, properties purchased, and lumber delivered, that Stickley was "all in." If his enthusiasm and naive optimism blinded him to the difficulties that lay ahead in the building of the structures, the setting up of a school, and the operation of a farm while running a furniture factory from a distance, starting a restaurant, and leasing a 12-story building in the heart of Manhattan (that was economically perilous from the start), his love of the property and belief that any day now it would become what he imagined, appear to have persisted almost to the end.

Formally, and even functionally, the designs for the Club House published in 1908 gave birth to the Log House as we experience it today. While there are differences–the dining room was extended the length of the house, a kitchen wing added to the rear, the second story was shingled, and the upstairs was reconfigured–the envelope of the building and the manner in which the spaces were to be used remained pretty consistent. One senses that instead of abandoning the Club House, as the Craftsman's House appears to have been, Stickley adapted it to better suit its new role as a family home. Rather than being scaled back into a structure that was more domestic in nature, it was reconfigured: the large built-in benches that defined the walls of the reception room were never installed, instead the fifty-foot long room used clustered furnishings and screens to create smaller seating areas that subdivided the space. In the upstairs, the repositioning of the staircase, the decision to reduce the large central sitting area in favor of an extra bedroom, removal of the ladies' dressing room, and the combining of the two south bedrooms into a single room meant that while the building would still work as the "Club House," it would better serve the needs of his family too. Even years after the family had moved into the Log House Stickley continued to refer to it as the "Club House," as though his dreams of a school and community were never dashed, but just deferred.

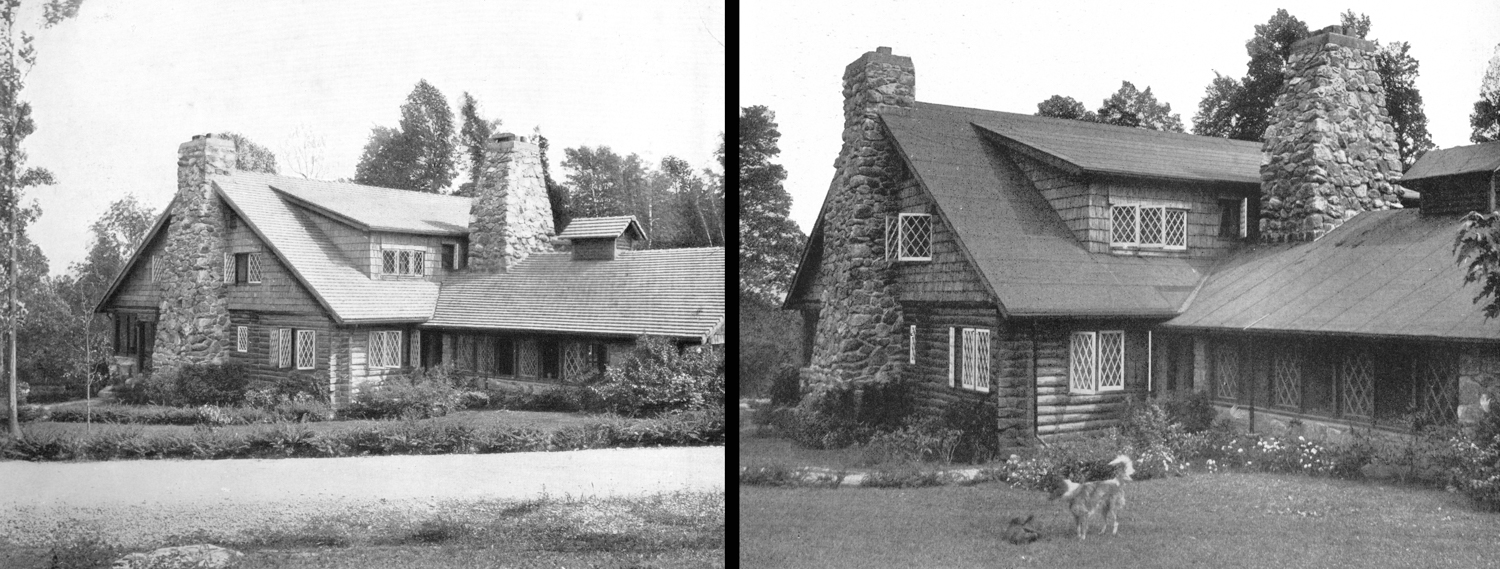

The Log House as it appeared in 1911, photographed for the November issue of The Craftsman.

The Log House today, curiously, differs from the plans published in The Craftsman, though not radically. In the upstairs hall, Stickley added a large closet on the long wall opposite the staircase, finishing the interior with tongue and groove gumwood paneling. We currently believe, based on the floor boards and evidence from the interior walls, that this change was made during the planning process, but it is also possible that the space was carefully adapted as the family lived in the home and new needs arose. In addition, Stickley showed a built in seat in what we call the Master Bedroom under the northern windows. We have found no evidence in the building of a missing built-in feature and now believe that the large cedar-lined chest probably had a cushion on top and was recorded in the 1917 inventory as a "seat."

At first glance, it would be easy to assume that the Log House was completed in the fall of 1911, that the family moved in, and that–with his attention focused on developing other parts of the property–the Log House remained essentially untouched through 1917. Pictures, however, published in the October 1913 issue of The Craftsman show that the green glazed Ludowici tiles had been installed, whereas the same view from the 1912 shows a roof covered with strips of what is likely Ruberoid. First used on roofs in 1892, the product was developed by the Standard Paint Company (from Bound Brook, New Jersey) in 1889 from proprietary mixture of infusorial earth and maltha, according to the patent application. This could then "be used directly upon a suitable sheathing or foundation, or may be applied to a suitable base or sheet of textile or fibrous material and used in the ordinary way as roofing fabric." By 1909, advertisements show that this was available in a number of colors, and archaeological evidence from in front of the Log House porch suggests that Stickley used a red coating, which would have harmonized with the Twin Cottage roofs visible to the north.

Seen on the left from the October 1913 issue of The Craftsman, the roof tiles have been installed. On the right, a similar view from 1912 still shows tar paper or Ruberoid on the roof.

Seen on the left from the October 1913 issue of The Craftsman, the roof tiles have been installed. On the right, a similar view from 1912 still shows tar paper or Ruberoid on the roof.

By 1917, and perhaps earlier in the home's history, a supplementary heating system had been installed in the Log House, no trace of which is visible in the extant photographs of the interior. Mentioned only in the advertising copy for prospective buyers of the estate prepared by George Howe, the document provides a number of glimpses into the property with a candor and exactitude that is often lacking in Stickley's own descriptions. "One of the notable features in the house," Howe wrote, "are the large beautiful rough stone fireplaces, each provided with Mr. Stickley's patent interior air heater, which makes it unnecessary except in very cold weather to operate the splendid heating sysytem which is installed in the house. This heating system is known as the steam vapor system, one of the latest and best systems of heating at present available."

The text of this notice conveys some of the desperation Stickley must have felt as he attempted to maintain solvency against ever-increasing odds. Estimating that Stickley spent approximately $250,000 developing the property, the asking price was $100,000 though Howe noted that "any reasonable bid will have careful consideration, and, if preferred, a proportion of the acreage could be left out." Eventually, the property sold to George and Sylvia Weinberg (later Farny) for a fraction of that: $60,000.