A view of the sunken garden, ca. 1913

Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Farms unfolded over time; it was never a moment fixed in amber. Craftsman Farms was an experience, or series of experiences, the result of a process of transformation and revision that happened by chance and by purpose. It was in Stickley’s time, much as it remains today, a series of ever-changing vignettes, choices, and circumstances that alternated between the accumulative and the destructive, reminding us that the fixed ideas we have about the property and its residents are but poor surrogates, shallow stand-ins for the richness of life that transpired during the Stickley family’s residence. Unfortunately, we cannot go back. Their lives here are something we will never fully recapture, never really revisit, and stories that remain unavailable to us, cloaked in a past that is largely inaccessible except for the fragmentary record that remains. On its own, that record–with all of its interesting objects, its snapshots of life, and snippets of text–is not enough. Things, in and of themselves, are mute witnesses to the lives that transpire around them. Recollections and texts are lovely to look at but hardly objective; like the humans who write them they are full of contradictions, inconsistencies, and aspirations, they are–like memory–a story we tell ourselves while unaware that we are spinning a yarn. Rediscovery, then, requires us to have a certain amount of empathy, imagination, and bit of courage. The choice, as I see it, is whether we cede these pasts as something condemned to the dustbin of history (because our understanding must by definition be imperfect) or whether we push forward with empathy and imagination in the hope that our imperfect fictions and stories we tell will contain some essential kernels of truth. In many ways, this notion is central to the exhibition; it is the shape to which these fluid ideas will conform.

Begun in 1908 with the initial purchases of land, Craftsman Farms took shape even before the family began living on the property, and in many ways is best thought of as Gustav Stickley's most ambitious project. But what did he intend it to be? Early on, he envisioned a school there, one in which the curriculum would be guided by the knowledge needed to complete real-world problems, and that freed boys from the stale environment of the classroom and kept them in touch with nature, where he believed they belonged. Although that dream never really died, it was put on hold and Craftsman Farms main role was that of a farm, supplying food to the restaurant atop his 12-story Craftsman Building in Manhattan. Then too, there was the thought, as the precarious nature of his financial position became more evident, that some of the land could be sold and–presumably so he could continue the dream of a community and turn an extra profit–Craftsman Houses could be built upon these plots. Regardless of what he intended the property to become, it became (and remains) a statement of his ambitions, his beliefs, his triumphs and his failings. Thus conceived, the property reads as an autobiography, a map onto which we can plot the points of his life, witness the manner in which he thought of his legacy, and see writ large the thoughts, tastes, ideas, and vision that drove him. It was, in essence, a laboratory for the fulfillment of his dreams. And though his time here was short, the memoir that was left–a text that unfolds over 650 acres and 9 years–is more powerful and insightful than anything he ever put into The Craftsman.

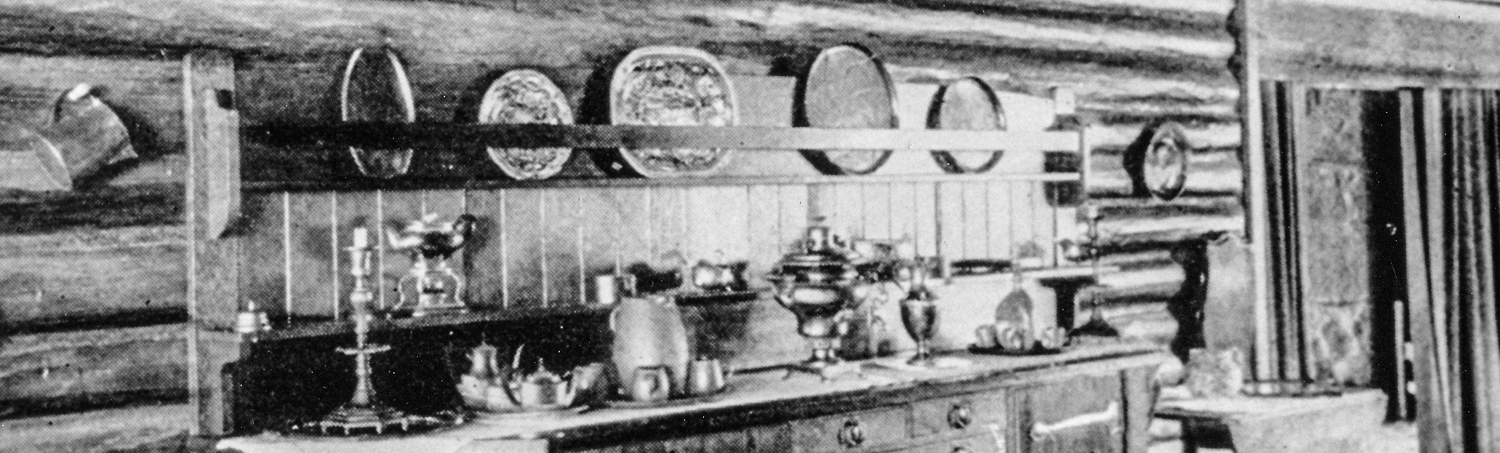

This exhibtion focuses mainly on the period that Stickley and his family lived at Craftsman Farms–from the completion of the cottages in the summer of 1910 to the sale of the property to George and Sylvia Farny in August of 1917. The title of this exhibition, Circa 1917, reflects my desire to capture that sense of evolution, indecision, and alteration that occurred throughout their time here. What interests me is the world that Stickley inhabited and what light that can shed upon his character. The things with which we surround ourselves become a kind of visual ecosystem through which we move; it is often more complex than we think. Mapping this system–looking carefully at the accumulation of "stuff" that inhabits our visual world–reveals layers of personal histories and choices that broadly define what we call “taste” or “style.” Often, the gulf between what we say we like and what we ultimately choose to surround ourselves with, forms little frictions that are illuminating. Stickley, for all his seeming forthrightness and the single-mindedness of much of what appeared in The Craftsman, was more complicated and opaque than we believe. There is, throughout his presentation of Craftsman Farms and himself, a kind of hide and reveal that hints at a remarkably private person whose personality, and even humanity, was suppressed to the point of obfuscation at times. As the objects in this exhibition demonstrate, his taste–something we take for granted because of his prominence in the Arts and Crafts movement–was complex and his interest in objects knew few boundaries. In the Log House–the best documented of the interiors on the property–the furniture he designed sat comfortably amongst an array of objects that included 19th century Staffordshire transferware, Art Nouveau, Wedgwood, Delft pottery, and Victorian silver and brass. To rediscover Craftsman Farms, then, is to rediscover Stickley, to look more closely at the choices he made and the things with which he surrounded himself. It is a chance to reimagine what we think we know of him, and how we conceive of the property and what it represents to us as caretakers and visitors.

Sideboard as pictured in the November 1911 issue of The Craftsman

The format that the exhibition takes, like the property itself, is the result of circumstances and choices that happened by chance and on purpose. I like that in a digital exhibition one can show details and comparisons that are often impossible in a physical exhibition. I am often frustrated by the fact that digital exhibitions come across as poor substitutes for expensive catalogs and do not take fuller advantage of the possibilities the medium offers. Knowing that between the uncertainty the pandemic posed during the planning process and then the destruction of the Annex in a freak tropical storm in the summer of 2020, we would be unable to mount a physical exhibition, the question became how to leverage the medium to make something impossible to do physically. The first revelation was that we could assemble a much larger amount of material than we could possibly host on site and bring together pieces from different institutions, descendants, and collectors to get a richer documentation of Stickley’s visual world than had been previously been done. I am grateful to Drs. Cynthia and Timothy McGinn, Barbara Fuldner, Nancy Calderwood, Lou Glessman, David and Susan Cathers, Peter Cook, The Gustav Stickley House Foundation, and Crab Tree Farms for access to and photographs of their collections. The second was realizing that we could leverage the technology that Northwestern University’s Knight Lab developed for journalists to make our historic photographs more interactive and show a level of detail that would be impossible in a printed catalog. Unlike a catalog which brings the audience along a prescribed path, the photographs allow you to explore the room more fully, taking the guideposts we have placed along the way in any order you wish, or ignoring them completely. My hope is that you will spend some time looking and questioning and add to the body of knowledge.

Lastly, physical catalogs are problematic for all museums, but most especially for smaller museums. They are expensive to write, expensive to layout and print, take space to store, and rarely are updated as a result. While they begin their lives as repositories of the latest knowledge, they soon age into moments locked in time. A digital exhibition has the potential to eliminate the burdensome upfront costs, have a much-reduced carbon footprint, and–unlike a book–can be nimble and respond to changing knowledge, even if this practice has not been widely adopted in the museum world. For that potential to be realized, we have to not only archive the exhibition, but revisit it from time to time, to make corrections and clarifications as the need arises. My belief is that all museums, but especially smaller ones, will benefit from leveraging tools–many of which are freely available–that expand access to their collections, present them in a new way, and allow audiences to rediscover, connect with, and explore our material culture. I hope you enjoy these efforts.

Jonathan Clancy

Director of Collections and Preservation