"AN EXPRESSION OF MODERN LIFE"

It is difficult, looking back, to conceive of The Arts and Crafts movement in 1900 as an expression of modern life: it has the look and feel of something quaint and old-fashioned. It has become a permanent past preserved in amber. Histories of the period–following the lead of historian T. J. Jackson Lears–have mostly framed it as an “anti-modern” movement, comprised mainly of idealists who rejected modern society and sought refuge in a comforting, if imaginary, past. At the same time, and often without any hint of irony, historians condemn the American movement because it relied too heavily upon the modern industrial system and was too capitalist–in essence, it was too modern and inconsistent. This exhibition makes a different argument: that the work of The United Crafts was fundamentally modern in that it addressed what Stickley called “the problems of daily existence.”

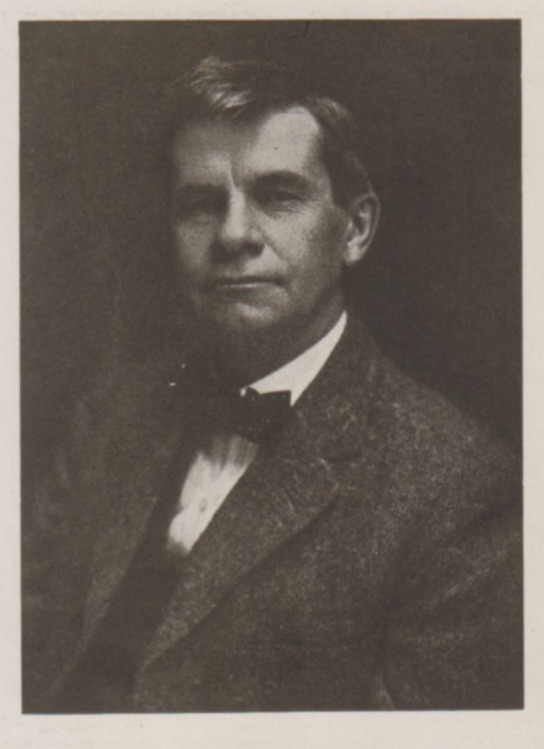

Lost in the discussion of anti-modernism and the Arts and Crafts are some crucial details of Stickley’s life which demonstrate an embrace and experience of modernity firsthand. Born in 1858, in Wisconsin, the arc of his subsequent decisions might be summarized as a constant move towards more densely populated areas, an increasing realization of the potential of technology, and drive towards a thoroughly modern integrated business model. He was born into a state that in 1860 had 776,000 people; by the time he published Things Wrought by The United Crafts in Syracuse, New York in 1902, that state’s population was in excess of 7.2 million people. Shortly thereafter, he moved his headquarters to New York City, the hub of modern commercial activity and the most populous city in the nation. Craftsman Farms, the home he built in Morris Plains was electrified, his children drove automobiles, and he purchased a 13-story building in Manhattan as a flagship retail store with restaurant on the top floor. Throughout this time, he continued to make furniture in a factory setting, using machinery to cut costs and–if we are to believe the movement’s philosophy–to reduce the mind-numbing drudgery of simple tasks for his employees. He marketed his wares nationally. He was, in essence, a thoroughly modern businessman.

And yet modernity for Stickley, like for many others, was a complicated blend of exhilaration, of possibility, and most certainly of fear. “Modern Life,” Irene Sargent told readers of The Craftsman in 1902, “is restless, pulsating and fretful, like the streaming rays of the aurora borealis." Most of these fears were centered around the effects of industrialism upon the individual, and while each generation described them as urgent matters in need of attention, they had persisted–with no viable solutions–since the birth of the industrial system in the eighteenth century. It emerged, and continued to be framed, as a binary between industrial and agricultural work that was expressed in fears about the moral worth of “city” versus “country” people. As early as 1776, political economist Adam Smith stated in Wealth of Nations that everyone acknowledged that the “lower ranks of people in the country are really superior to those of the town.” Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, a diverse group of authors including Thomas Carlyle, Karl Marx, and Ralph Waldo Emerson each fretted about the negative influences of what Carlyle dubbed “A Mechanical Age” upon the individual. This long nineteenth century–as it is sometimes called–was marked not only by the material advances of a progressive, industrial society, but concerns that the spiritual nourishment of mankind would lead to a splintered, fractured self who would awaken to a world in which the very progress that should give rise to celebration was mired in a sense of dissatisfaction and dislocation that made life unbearable. Although the Arts and Crafts movement was especially concerned with these problems, it had no monopoly on identifying, let alone solving, these issues. Rather, these were persistent concerns increasingly raised over a long period marked by increasing industrialization and urbanization.

Although very few of Stickley’s personal writings survive from this period, the articles that appeared The Craftsman are useful to understanding how the United Crafts wrestled with these issues, and what solutions the firm could provide to the broader audience. In hindsight, Stickley’s initial impulse for the magazine was not simply to sell people furniture–which, as a furniture manufacturer might be expected–but to sell them upon the ideas and philosophies that would make his furniture appealing. While he kept readers abreast on his firm’s work and illustrated a handful of pieces in each issue, the larger issues being addressed were often: how does one navigate modern life in a manner that preserves the integrity of the self, but is able to enjoy the full range of life’s offerings? And: Can one learn to love and embrace the best things about modernity without losing one’s self?

The solution proposed by Stickley was not to flee modernity but to adapt the most sacred of spaces–the home–to provide relief from the “pulsating and fretful” aspects of modernity that were thought to be especially pernicious. If the vocabulary he used–his Arts and Crafts aesthetic–was different, the notion of the home as refuge was remarkably traditional. Even his insistence that the natural world served a soothing, spiritual balm for humanity was, as he described in The Craftsman, derived from “a course of reading, largely of Ruskin and Emerson, which I followed in my youth.” The home, and especially the furnishings within the home, were treated both as functional and metaphorical objects designed–as Stickley noted–to add to “the ease and convenience of life; or… furthering the equally important object of providing agreeable, restful and invigorating effects of form and color, upon which the eye shall habitually fall, as the problems of daily existence present themselves for solution.”

THE UNITED CRAFTS AND THEIR MARKET

"Certain colors were created to rest and restore the tired visual organ, and chief among them is green."

Things Wrought by The United Crafts at Eastwood New York

While we cannot know with certainty the motivations that drove the original buyer of this furniture to make the purchase, we can gain some sense of the metaphoric meaning behind the furniture in this group, as well as Stickley’s aesthetic in general through the firm’s writings. The color green, he informed readers, was restful and restorative; in this sense the choice is consonant with the use of it in a family seating area, as opposed to the brown oak of the office furniture in this order. Read through this lens, the different woods and finishes chosen for the different spaces of this house were not arbitrarily different, but used to signify and differentiate spaces with very distinct functions. While quite faded today, it is useful to remember that there was, initially, a far greater gulf between the solemnity and warmth of the oak pieces in the order and the vibrancy of the bright, green ash pieces.

The precise date the original order was placed has been lost to history, but the extant pieces from the cache are able to tell a broader story about the purchasing process and the use of catalogs than has previously been undertaken. Although it was initially suggested that these pieces were ordered from one of Stickley’s catalogs–perhaps his 1901 Chips from the Workshops of the United Crafts–that cannot be possible because no known catalog contains all of the pieces that comprise this order. Indeed, the diminutive Table (no. 415) does not appear in any extant catalog, but did appear later as a line drawing in advertisements. This suggests a number of things: first, the purchase was probably made by visiting a retailer and selecting furniture from either a number of catalogs or an as yet undiscovered set of retail plates, which would explain the line drawing for table (no. 415). Second, because the pieces are only found in a number of catalogs–and because the Inventories and Sales Journals demonstrate a longer duration for production of pieces than typically presumed–it means that we need to think of these early catalogs not as representing the whole of the company’s productions, but rather as new offerings that were added to the existing line of furniture. Lastly, because retailers had displays of United Crafts furniture which were set up to entice customers, it is possible that one or more pieces of this furniture was selected result of existing stock, not something newly made. While individual pieces could have been produced from as early as 1900 to as late as 1904, the whole cache of furniture–as documented in the factory inventories and sales ledgers–could only have been produced and purchased between 1901 and 1902.

The cost of Stickley’s furniture made it generally available only to the middle upper and upper classes, although individual pieces were sometimes be affordable to a truly middle-class audience. Although oak was the predominate material throughout Stickley’s career in the Arts and Crafts movement, ash furniture was made from about 1901-03, and mahogany was available generally from 1898-1915, though there was often a premium charged for it. The catalogs often spoke of a middle-class audience, but there is little evidence to suggest that furnishing a home in furniture from the firm would have been within the reach of many middle-class families.

Calculated in today’s dollars, this order of furniture–which cost the client $487.25–is equivalent to $14,796. If this is useful to give some sense of the value, it is a blunt tool that divorces the idea of labor from the monetary cost of the furniture. To put this in perspective, it is useful to consider that a laborer in Stickley’s factory made $1.25 per day for a weekly paycheck of $7.50. for that laborer then, the furniture cost almost sixty-five weeks of work. For the higher paid workers in the factory, those craftsmen who made $20 per week, this order represented an investment of nearly twenty-five weeks of work to buy. Even Stickley, who paid himself $100 per week, would have had to devote over a month of his labor to afford an order of this size. Even these calculations fail to paint an accurate picture of the cost of this furniture that an audience today is able to relate to for, unlike today, the average work week at Stickley’s factory was sixty hours. That means that for one of the higher paid craftsmen in the factory, in today’s terms the cost is closer to thirty-six weeks of labor, or a total of nine months’ labor. Simply put, if the dream was for a more democratic art that could help shape the middle-class home, then it would be realized not through manufacturers like the United Crafts. It was only as this aesthetic influence was adopted by firms who could affordably produce furniture for the mass-market that these aspirations would be realized.

MODERN ART AND THE UNITED CRAFTS: A REASSESSMENT

The essential function of art, Irene Sargent wrote in The Craftsman, “is to hold the mirror up to nature,” something that the United Crafts achieved both literally–by looking to nature for inspiration–and metaphorically by seeking to imbue the home with a sense of stability and restfulness that was a necessary relief from the chaos of modernity. Today, as in the past, it is easy to think of the movement as out of touch, to view its reverence for the Gothic and heroic adoration of the guild system as fundamentally anti-modern, but to do so misses the point. Modern art has always drawn upon the past, and it is in precisely this period that Picasso was looking back at Iberian sculpture, that Paul Gaugin was exploring Breton culture, or that Mikhail Larionov was mining the language of traditional folk painting to help shape their distinctive modernisms. None of these artists sought a return to times past, but instead wanted to inject a sense of vitality and freedom into a modern culture that seemed stiff and mechanized. If we accept these artists as modernists–in spite of their extensive use of the past to shape their visions–why would we treat the furniture made by The United Crafts any differently?

Modern life was, as it continues to be, a messy affair for most of us. Pulled by the contradictory impulses of discovering the new potentials that technology offers us, we may still cling to older ideas of ourselves and of our past that we would like to preserve. Modern life, as I understand it, is not the fantastic futurism of fantasy but that messy and often contradictory process by which we navigate, choose to discard, embrace, shun, celebrate, and are ashamed of our decisions. It is inherently inconsistent, but not because of any flawed frailty that we need be troubled by. It is contradictory because of our perfect humanity, not in spite of it. As Walt Whitman wrote in “Song of Myself, 51”: “Do I contradict myself? Very well then I contradict myself, (I am large, I contain multitudes.)” Writing in The Craftsman in 1909, Ernest Batchelder cogently defended the movement as an expression of modern life, and blunted the criticisms that still persist today:

To criticize the movement as being out of touch with modern thought is to misinterpret its best ideals. It seeks to bring a better standard to industrial work, establish a permanent demand for better things, and furnish an adequate livelihood for those who are competent to give beauty to hand work. It does not necessarily antagonize machinery, nor does it hope to achieve its ends through a reversion to primitive methods.

Sources:

For the quote "the problems of daily existence," see: "Forward," The Craftsman 1 (October 1901): unpaginated.

Sargent's "restless, pulsating, and fretful" comes from: Irene Sargent, “Color: An Expression of Modern Life,” The Craftsman (September 1902): 264.

For Ernest Batchelder's quote see: Ernest A. Batchelder, “The Arts and Crafts Movement in America: Work or Play?” The Craftsman 16 (August 1909): 547.