Closer Looking: Art & Design

Online Course for Winter-Spring 2023

COURSE DESCRIPTION

Closer Looking: Art and Design is an online course that explores great objects. Rather than confine our gaze to a single moment or a location, this series picks from the broad range of human achievement and seeks to expose you to new ideas and forms, to cultivate the sense of wonder and awe inherent in learning, and to equip participants with the tools to better understand the rewards of closer looking in their own lives. It is, inherently, an argument against the temptation for “distractions,” for “multi-tasking,” and the frenetic pace with which information comes at us and a reminder that the act of looking at–and truly seeing–an object is itself a reward. Slow and close looking quiets the mind and allows for those transcendent experiences that Joseph Campbell called “a radiance” that holds you in “aesthetic arrest.” It is a reminder that Art and Design are not just pretty things, but necessary things that allow us to move beyond our own thoughts and experiences and connect more fully with each other and the world around us.

By dividing the sessions into categories (like lighting or sculpture) as opposed to chronologies we move beyond the shallow notion that history progresses linearly and think more deeply about the objects’ aesthetics as a series of choices and negotiations. Caught between the competing realities of the maker, the era, the patron, and the audience, objects can both reflect and transcend the limitations of these histories, but only if we take the time to experience them. Each hour-long session features a maximum of ten objects to explore, to think through, and to see in a new way.

In truth, there is no absolute canon that we will look towards to guide us along this path; instead, the objects are selected for their aesthetic qualities, their novel approach to problem solving, or because of the compelling lives of those associated with it. Some choices may be familiar–even obvious–but many, I hope, will be a revelation. The goal is to slow down, to cultivate your inherent curiosity, and to see some great art and design in the hope that–with practice–you’re able to regularly experience those moments of awe and radiance in your own life.

ABOUT THE INSTRUCTOR

Dr. Jonathan Clancy is the Director of Collections and Preservation at the Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms. An author, educator, and curator Clancy received his doctorate in art history in 2008 from the Graduate Center. Formerly Director of the MA in American Fine and Decorative Arts program at Sotheby’s, he left in 2017 to form an advisory group. As an independent consultant, he has worked with private clients and institutions on collection management, exhibition planning, label writing and research, and valuation.

Registration is required. Once registered and paid, you will receive an email prior to each session with a link to join.

Do you have a scheduling conflict for the live session? You can still enjoy the program. Register and we’ll send you the recording! All paid attendees will be emailed a private link to the session recording when it is available, typically 4-5 days after the live program.

Missed us? You can also register retroactively. If you register for a session that has passed, you’ll receive access to the recording when it is ready.

Haven’t tried a session yet? Each session is planned as a “stand-alone” lecture, so you can take them all or attend the topics that interest you most.

SCHEDULE

Series 1: Prints and Works on Paper

| 1 | Sat., Jan. 28, 2023 | Prints and the Spread of Visual Culture Printed works–from Hokusai’s woodblocks to Rembrandt’s etchings to Jasper Johns’ graphic work–have both reflected and shaped their cultures. Produced in greater number than singular works of art, prints move more quickly and widely and through societies, transmitting ideas and iconography in ways that most singular works cannot. Prints, in many ways, made artists more widely-known and their art more accessible by reducing the cost of owning examples and placing examples in the hands of the many rather than restricting it to the few. Through original pieces as well as copies of works in other media prints helped form and expand a common visual language that continues to persist today. |  Albrecht Durer, Melancholia I, 1514. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

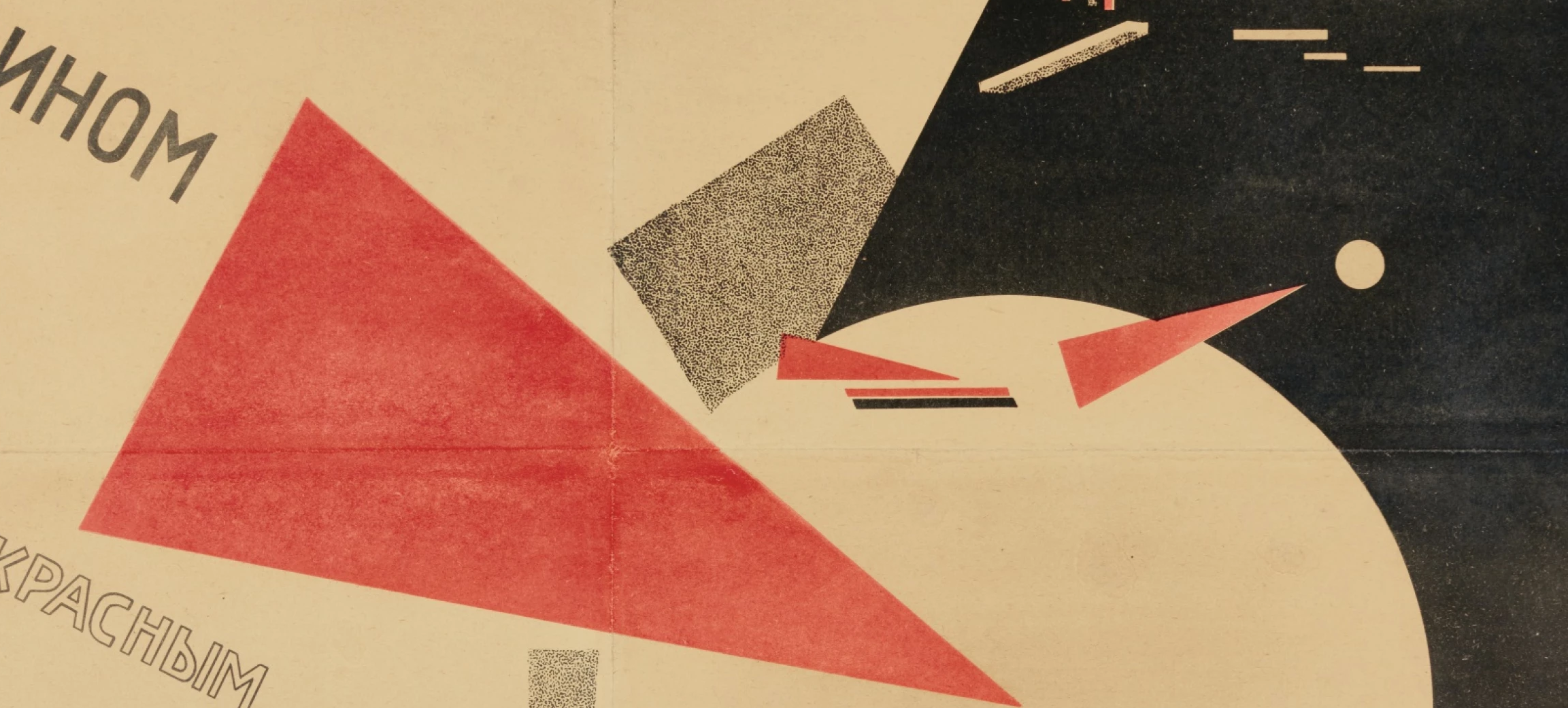

| 2 | Sat., Feb. 4, 2023 | The Print as Propaganda The wider distribution of prints made them extraordinarily useful as message carriers, exposing audiences to constant streams of propaganda both noble and nefarious. No sector was immune to the potential of the printed medium as a commercial tool for either goods or ideas as the examples in this session–whether sacred or profane–demonstrate. From the oldest know printed works in the ninth century to works by artists hired by the WPA during the Great Depression to punk rock fliers of the 1980s through today, the medium has enabled the dissemination of messages that unite, divide, confirm, and question the established orders. The ubiquity with which various propagandas populate our visual and aural worlds can make them particularly difficult to identify which–when those messages enable violence or hatred–can be particularly dangerous for the society. |  El Lissitzky, Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge, 1919-20. Sotheby’s. |

| 3 | Sat., Feb. 11, 2023 | Woodblocks and Graphic Arts in the Arts and Crafts Movement Print culture in the Arts and Crafts movement reflected the many influences that combines to help define the era, from medievalism, to Japonisme, to Art Nouveau, and an appreciation of the natural world. In many ways, the use of prints and the colors they provided help shape the Arts and Crafts interior and served as a reflection of the values that audiences associated with the movement. From well-known figures like Arthur Wesley Dow and Dard Hunter, to less familiar figures like Swedish-born B. J. O. Nordfelt, this session looks closely at great examples of prints for the Arts and Crafts home. |  Arthur Wesley Dow, Rain in May, ca. 1907. Sotheby’s |

Series 2: Lighting

| 4 | Sat., Feb. 25, 2023 | Lighting 1 Accessories for lighting–from candlesticks, to oil lamps, to electric fixtures–have shaped the way we live while reflecting the artistic abilities of their makers and the aesthetics of their time and place. In addition to the practical and functional benefits of lighting, there is an emotional quality to it because it helps to shape and define the “feel” of the spaces it illuminates. In this session, we’ll look at examples that span more than 2000 years of innovation and look closely at artistic examples of lighting from Indonesia to England to China and beyond. |  Hanging Lamp in the form of a Kinnari, ca. 850-900. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 5 | Sat., March 4, 2023 | Lighting of the Arts and Crafts Movement Rising to prominence just as electric lighting was become more popular, the Arts and Crafts movement–in the United States and abroad–often reveled in historicism while at the same time embracing the artistic potential of this new technology. While some exploited this sense of newness with enthusiasm and wrapped it in a thoroughly modern aesthetic, others sought the comfort of history or nature as a means to temper the shock of the new and soften the incorporation of this emerging technology in the home. This session dives deeply into 10 great examples of lighting from the Arts and Crafts movement as a means to explore the tension between modernity and the lure of history. |  Charles Robert Ashbee (des.) for the Guild of Handicraft, Chandelier, 1895 |

Series 3: The Minor Arts

| 6 | Sat., March 18, 2023 | The Minor Arts Part 1 In spite of (or perhaps because of) the specificity with which we classify and sort the decorative arts–furniture, textiles, metals, and ceramics etc.–there are a number of works that hover around the edges and never fit comfortably into the slots we have created. With no clear category to assign them to, the works are thus minimized, if not altogether ignored. In the course of these two sessions, we’ll explore the artistry of these overlooked disciplines, sometimes referred to in the 18th century as “the minor arts.” From paper filigree, to sand art, to scrimshaw and hair- and shellwork, these works–often the purview of marginalized communities outside of mainstream craft industries–reveal an exceptional level of talent and creative vision that testify to the breadth with which art and design ideals spread throughout the larger world. |  Bridget Noyes, Detail of a Sconce, ca. 1720. Wadsworth Atheneum. |

| 7 | Sat., April 1, 2023 | The Minor Arts Part 2 In spite of (or perhaps because of) the specificity with which we classify and sort the decorative arts–furniture, textiles, metals, and ceramics etc.–there are a number of works that hover around the edges and never fit comfortably into the slots we have created. With no clear category to assign them to, the works are thus minimized, if not altogether ignored. In the course of these two sessions, we’ll explore the artistry of these overlooked disciplines, sometimes referred to in the 18th century as “the minor arts.” From paper filigree, to sand art, to scrimshaw and hair- and shellwork, these works–often the purview of marginalized communities outside of mainstream craft industries–reveal an exceptional level of talent and creative vision that testify to the breadth with which art and design ideals spread throughout the larger world. |  M. Kunst, Hairwork picture, 1856. Lanyon Homestead, Tharwa Australia. |

Series 4: Painting and the Fine Arts

| 8 | Sat., April 15, 2023 | Painting and the Fine Arts Part 1 Paintings–from the Fayum mummy portraits to works of contemporary artists–have been given a privileged place among the arts that continues to dominate the way art is taught and consumed by audiences. Time-consuming to make, expensive to acquire, and often few in number, the history of painting often reads like a history of elitism in which the importance of patrons and the individual genius of these artists dominate the discussion. In this session, we look more closely at the craft of painting, seeing the objects not only as narrative or ideological vehicles but as an accumulation of choices (both taken and ignored) that helped to produce the effect of the finished work. As we have throughout this series, we will ignore chronological progressions and focus instead on quality works made in disparate times and places. The goal is to introduce you to new objects, new artists, and new ways of looking at and thinking about art. |  Jean-Michel Basquiat, Do Not Revenge (detail), 1982. Christie’s. |

| 9 | Sat., April 22, 2023 | Painting and the Fine Arts Part 2 In 1982, a curious thing happened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: there was a sudden drop in audiences’ interest in one of the museum’s beloved Rembrandt’s because of two words added to the label. That shift–from Rembrandt to “Follower of” Rembrandt–is remarkable because it tells us a lot about how we look at art. As then Director Phillipe de Montebello noted, nothing about the painting itself had changed, what had shifted was audiences’ attitudes towards the painting. Oftentimes, it turns out, we prioritize the label over the object and (whether intentionally or not) this hampers our ability to really “see” the object. In this session, we will try to look beyond the labels, to think about form and technique, and to see new and familiar works with fresh eyes and open minds. |  Follower of Rembrandt, Portrait of A Man (detail), ca. 1658-62. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 10 | Sat., April 29, 2023 | Painting and the Fine Arts Part 3 Continuing our romp through the broad history of painting without regard for chronology or stylistic succession, our final week in this series continues to avoid the works everyone knows–I’m thinking of you Mona Lisa–in favor of thinking through choices, execution, and aesthetics. In sidestepping some of the most canonical works (and indeed some of the most canonical artists) we gain the opportunity to look at art without the burden of history and the expectations that creates within us. In so doing, I would argue, we can recapture the essence of what makes an object powerful: an emotional resonance that is more lasting than any intellectual appreciation. |  George Bellows, The Lone Tenement (detail), 1909. National Gallery of Art. |

Series 5: Copper

| 11 | Sat., May 6, 2023 | Development of Artistic Copper in the US Coinciding with the opening of The First Metal: Arts & Crafts Copper at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon on May 06, 2023, this is the first of three classes devoted to Artistic Copper in the Arts and Crafts Period. In this first session, we look at the unlikely rise of copper as an art form, considering the impact of design manuals, Industrial Arts education, and the previously overlooked role that amateur women played in transforming the medium into a vibrant and economically viable pursuit. The exhibition runs until November 03, 2024, and a catalog is available. |  Urn (English), ca. 1750. Image courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum. |

| 12 | Sat., May 13, 2023 | English Copper and the American Arts and Crafts In this session we explore the development of artistic coppersmithing during the English Arts and Crafts movement and the impact this had on American practitioners. Featuring works in the exhibition by Harry C. Hall, John Pearson, The Birmingham Guild of Handicraft, Albert Edward Jones and others, we’ll look at the development of the English aesthetic and the impact this had on Americans during the end of the nineteenth century. The breadth of design possibility for copper is evident not only in the diverse work of these artists but in the many unsigned examples that circulated in the period as well. |  John Pearson, Detail of a Dish, 1890. Image courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum. |

13 | Sat., May 20, 2023 | Artistic Copper in America comes of age. Once the groundwork of a market had been laid by talented amateurs and Americans realized the success that some of their English counterparts were enjoying, the professionalization of artistic copper in the United States happened rapidly. In this session, we’ll explore some works by artists and firms we’ve looked at before–Stickley’s Craftsman Workshops and Roycroft for example–as well as look more closely at artists we’ve previously passed over or only touched upon briefly like Otto Heinz, Albert Berry, and Hans Jauchens. We will examine both the continuity and divergence from English precedents and see the speed at which an artistic medium that was virtually unknown in 1900 came to be widely practiced at the height of the Arts and Crafts movement. |  Heintz Art Metal, pen tray, ca. 1905-12. Courtesy of the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art. |

MORE INFORMATION:

Craftsman Farms, the former home of noted designer Gustav Stickley, is owned by the Township of Parsippany-Troy Hills and is operated by The Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms, Inc., (“SMCF”) (formerly known as The Craftsman Farms Foundation, Inc.). SMCF is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization incorporated in the State of New Jersey. Restoration of the National Historic Landmark, Craftsman Farms, is made possible, in part, by a Save America’s Treasures Grant administered by the National Parks Service, Department of the Interior, and by support from the Morris County Historic Preservation Trust, The New Jersey Historic Trust, and individual donors. SMCF received an operating support grant from the New Jersey Historical Commission, a division of the Department of State and a grant from the New Jersey Arts & Culture Recovery Fund of the Princeton Area Community Foundation. Educational programs are funded, in part, by grants from the Arts & Crafts Research Fund.