*PLEASE NOTE: The live, online sessions of these classes have passed. Register here to receive a private link to the recording of the live sessions when they are available to view online.

Haven’t tried a session yet? Each session is planned as a “stand-alone” lecture, so you can take them all or select the topics that interest you most.

Jump to 2020 Online Class Archive

2023 Online Class Archive:

Closer Looking: Art and Design: 13 sessions; Recorded Jan. 28 – May 20, 2023.

Closer Looking: Sculpture and the Plastic Arts: 3 sessions; Recorded Sep. 9 – Sep. 23, 2023

Becoming Stickley: 5 sessions; Recorded Oct. 21 – Dec. 2, 2023

2023

Closer Looking: Art and Design

Closer Looking: Art and Design is an online course that explores great objects. Rather than confine our gaze to a single moment or a location, this series picks from the broad range of human achievement and seeks to expose you to new ideas and forms, to cultivate the sense of wonder and awe inherent in learning, and to equip participants with the tools to better understand the rewards of closer looking in their own lives. It is, inherently, an argument against the temptation for “distractions,” for “multi-tasking,” and the frenetic pace with which information comes at us and a reminder that the act of looking at–and truly seeing–an object is itself a reward. Slow and close looking quiets the mind and allows for those transcendent experiences that Joseph Campbell called “a radiance” that holds you in “aesthetic arrest.” It is a reminder that Art and Design are not just pretty things, but necessary things that allow us to move beyond our own thoughts and experiences and connect more fully with each other and the world around us.

By dividing the sessions into categories (like lighting or sculpture) as opposed to chronologies we move beyond the shallow notion that history progresses linearly and think more deeply about the objects’ aesthetics as a series of choices and negotiations. Caught between the competing realities of the maker, the era, the patron, and the audience, objects can both reflect and transcend the limitations of these histories, but only if we take the time to experience them. Each hour-long session features a maximum of ten objects to explore, to think through, and to see in a new way.

In truth, there is no absolute canon that we will look towards to guide us along this path; instead, the objects are selected for their aesthetic qualities, their novel approach to problem solving, or because of the compelling lives of those associated with it. Some choices may be familiar–even obvious–but many, I hope, will be a revelation. The goal is to slow down, to cultivate your inherent curiosity, and to see some great art and design in the hope that–with practice–you’re able to regularly experience those moments of awe and radiance in your own life.

| 1 | Sat., Jan. 28, 2023 | Prints and the Spread of Visual Culture Printed works–from Hokusai’s woodblocks to Rembrandt’s etchings to Jasper Johns’ graphic work–have both reflected and shaped their cultures. Produced in greater number than singular works of art, prints move more quickly and widely and through societies, transmitting ideas and iconography in ways that most singular works cannot. Prints, in many ways, made artists more widely-known and their art more accessible by reducing the cost of owning examples and placing examples in the hands of the many rather than restricting it to the few. Through original pieces as well as copies of works in other media prints helped form and expand a common visual language that continues to persist today. |  Albrecht Durer, Melancholia I, 1514. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 2 | Sat., Feb. 4, 2023 | The Print as Propaganda The wider distribution of prints made them extraordinarily useful as message carriers, exposing audiences to constant streams of propaganda both noble and nefarious. No sector was immune to the potential of the printed medium as a commercial tool for either goods or ideas as the examples in this session–whether sacred or profane–demonstrate. From the oldest know printed works in the ninth century to works by artists hired by the WPA during the Great Depression to punk rock fliers of the 1980s through today, the medium has enabled the dissemination of messages that unite, divide, confirm, and question the established orders. The ubiquity with which various propagandas populate our visual and aural worlds can make them particularly difficult to identify which–when those messages enable violence or hatred–can be particularly dangerous for the society. |  El Lissitzky, Beat the Whites with the Red Wedge, 1919-20. Sotheby’s. |

| 3 | Sat., Feb. 11, 2023 | Woodblocks and Graphic Arts in the Arts and Crafts Movement Print culture in the Arts and Crafts movement reflected the many influences that combines to help define the era, from medievalism, to Japonisme, to Art Nouveau, and an appreciation of the natural world. In many ways, the use of prints and the colors they provided help shape the Arts and Crafts interior and served as a reflection of the values that audiences associated with the movement. From well-known figures like Arthur Wesley Dow and Dard Hunter, to less familiar figures like Swedish-born B. J. O. Nordfelt, this session looks closely at great examples of prints for the Arts and Crafts home. |  Arthur Wesley Dow, Rain in May, ca. 1907. Sotheby’s |

| 4 | Sat., Feb. 25, 2023 | Lighting 1 Accessories for lighting–from candlesticks, to oil lamps, to electric fixtures–have shaped the way we live while reflecting the artistic abilities of their makers and the aesthetics of their time and place. In addition to the practical and functional benefits of lighting, there is an emotional quality to it because it helps to shape and define the “feel” of the spaces it illuminates. In this session, we’ll look at examples that span more than 2000 years of innovation and look closely at artistic examples of lighting from Indonesia to England to China and beyond. |  Hanging Lamp in the form of a Kinnari, ca. 850-900. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 5 | Sat., March 4, 2023 | Lighting of the Arts and Crafts Movement Rising to prominence just as electric lighting was become more popular, the Arts and Crafts movement–in the United States and abroad–often reveled in historicism while at the same time embracing the artistic potential of this new technology. While some exploited this sense of newness with enthusiasm and wrapped it in a thoroughly modern aesthetic, others sought the comfort of history or nature as a means to temper the shock of the new and soften the incorporation of this emerging technology in the home. This session dives deeply into 10 great examples of lighting from the Arts and Crafts movement as a means to explore the tension between modernity and the lure of history. |  Charles Robert Ashbee (des.) for the Guild of Handicraft, Chandelier, 1895 |

| 6 | Sat., March 18, 2023 | The Minor Arts Part 1 In spite of (or perhaps because of) the specificity with which we classify and sort the decorative arts–furniture, textiles, metals, and ceramics etc.–there are a number of works that hover around the edges and never fit comfortably into the slots we have created. With no clear category to assign them to, the works are thus minimized, if not altogether ignored. In the course of these two sessions, we’ll explore the artistry of these overlooked disciplines, sometimes referred to in the 18th century as “the minor arts.” From paper filigree, to sand art, to scrimshaw and hair- and shellwork, these works–often the purview of marginalized communities outside of mainstream craft industries–reveal an exceptional level of talent and creative vision that testify to the breadth with which art and design ideals spread throughout the larger world. |  Bridget Noyes, Detail of a Sconce, ca. 1720. Wadsworth Atheneum. |

| 7 | Sat., April 1, 2023 | The Minor Arts Part 2 In spite of (or perhaps because of) the specificity with which we classify and sort the decorative arts–furniture, textiles, metals, and ceramics etc.–there are a number of works that hover around the edges and never fit comfortably into the slots we have created. With no clear category to assign them to, the works are thus minimized, if not altogether ignored. In the course of these two sessions, we’ll explore the artistry of these overlooked disciplines, sometimes referred to in the 18th century as “the minor arts.” From paper filigree, to sand art, to scrimshaw and hair- and shellwork, these works–often the purview of marginalized communities outside of mainstream craft industries–reveal an exceptional level of talent and creative vision that testify to the breadth with which art and design ideals spread throughout the larger world. |  M. Kunst, Hairwork picture, 1856. Lanyon Homestead, Tharwa Australia. |

| 8 | Sat., April 15, 2023 | Painting and the Fine Arts Part 1 Paintings–from the Fayum mummy portraits to works of contemporary artists–have been given a privileged place among the arts that continues to dominate the way art is taught and consumed by audiences. Time-consuming to make, expensive to acquire, and often few in number, the history of painting often reads like a history of elitism in which the importance of patrons and the individual genius of these artists dominate the discussion. In this session, we look more closely at the craft of painting, seeing the objects not only as narrative or ideological vehicles but as an accumulation of choices (both taken and ignored) that helped to produce the effect of the finished work. As we have throughout this series, we will ignore chronological progressions and focus instead on quality works made in disparate times and places. The goal is to introduce you to new objects, new artists, and new ways of looking at and thinking about art. |  Jean-Michel Basquiat, Do Not Revenge (detail), 1982. Christie’s. |

| 9 | Sat., April 22, 2023 | Painting and the Fine Arts Part 2 In 1982, a curious thing happened at the Metropolitan Museum of Art: there was a sudden drop in audiences’ interest in one of the museum’s beloved Rembrandt’s because of two words added to the label. That shift–from Rembrandt to “Follower of” Rembrandt–is remarkable because it tells us a lot about how we look at art. As then Director Phillipe de Montebello noted, nothing about the painting itself had changed, what had shifted was audiences’ attitudes towards the painting. Oftentimes, it turns out, we prioritize the label over the object and (whether intentionally or not) this hampers our ability to really “see” the object. In this session, we will try to look beyond the labels, to think about form and technique, and to see new and familiar works with fresh eyes and open minds. |  Follower of Rembrandt, Portrait of A Man (detail), ca. 1658-62. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 10 | Sat., April 29, 2023 | Painting and the Fine Arts Part 3 Continuing our romp through the broad history of painting without regard for chronology or stylistic succession, our final week in this series continues to avoid the works everyone knows–I’m thinking of you Mona Lisa–in favor of thinking through choices, execution, and aesthetics. In sidestepping some of the most canonical works (and indeed some of the most canonical artists) we gain the opportunity to look at art without the burden of history and the expectations that creates within us. In so doing, I would argue, we can recapture the essence of what makes an object powerful: an emotional resonance that is more lasting than any intellectual appreciation. |  George Bellows, The Lone Tenement (detail), 1909. National Gallery of Art. |

| 11 | Sat., May 6, 2023 | Development of Artistic Copper in the US Coinciding with the opening of The First Metal: Arts & Crafts Copper at the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art at the University of Oregon on May 06, 2023, this is the first of three classes devoted to Artistic Copper in the Arts and Crafts Period. In this first session, we look at the unlikely rise of copper as an art form, considering the impact of design manuals, Industrial Arts education, and the previously overlooked role that amateur women played in transforming the medium into a vibrant and economically viable pursuit. The exhibition runs until November 03, 2024, and a catalog is available. |  Urn (English), ca. 1750. Image courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum. |

| 12 | Sat., May 13, 2023 | English Copper and the American Arts and Crafts In this session we explore the development of artistic coppersmithing during the English Arts and Crafts movement and the impact this had on American practitioners. Featuring works in the exhibition by Harry C. Hall, John Pearson, The Birmingham Guild of Handicraft, Albert Edward Jones and others, we’ll look at the development of the English aesthetic and the impact this had on Americans during the end of the nineteenth century. The breadth of design possibility for copper is evident not only in the diverse work of these artists but in the many unsigned examples that circulated in the period as well. |  John Pearson, Detail of a Dish, 1890. Image courtesy of the Victoria & Albert Museum. |

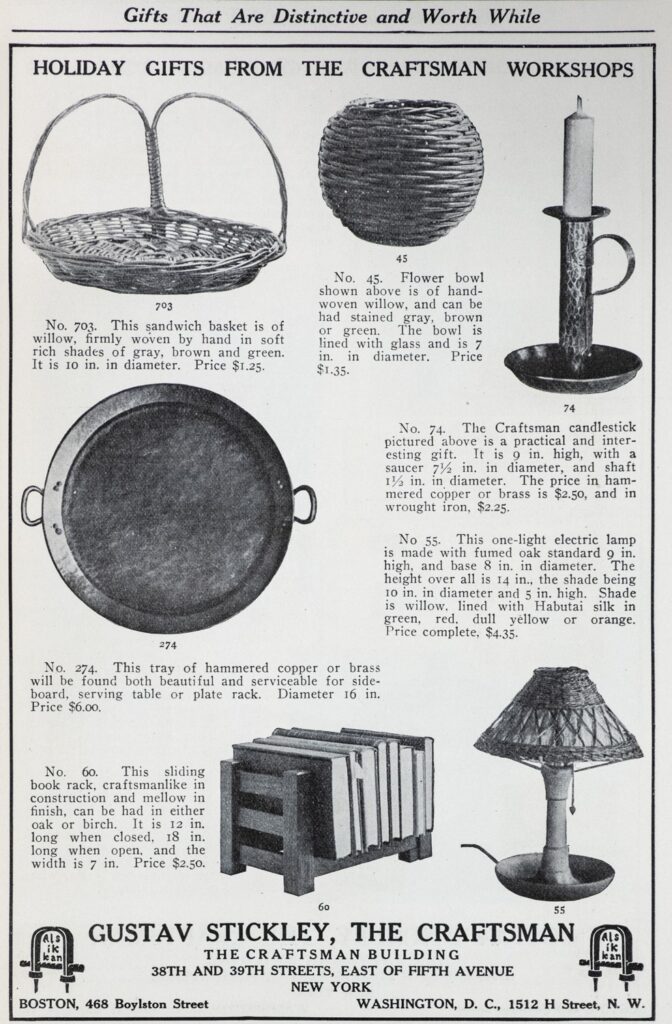

| 13 | Sat., May 20, 2023 | Artistic Copper in America comes of age. Once the groundwork of a market had been laid by talented amateurs and Americans realized the success that some of their English counterparts were enjoying, the professionalization of artistic copper in the United States happened rapidly. In this session, we’ll explore some works by artists and firms we’ve looked at before–Stickley’s Craftsman Workshops and Roycroft for example–as well as look more closely at artists we’ve previously passed over or only touched upon briefly like Otto Heinz, Albert Berry, and Hans Jauchens. We will examine both the continuity and divergence from English precedents and see the speed at which an artistic medium that was virtually unknown in 1900 came to be widely practiced at the height of the Arts and Crafts movement. |  Heintz Art Metal, pen tray, ca. 1905-12. Courtesy of the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art. |

2023

Closer Looking: Sculpture and the Plastic Arts

Closer Looking: Sculpture and the Plastic Arts is an online course that explores great objects and serves as an addendum to our Closer Looking Series. The premise remains simple: rather than confine our gaze to a single moment or a location, this series picks from the broad range of human achievement and seeks to expose you to new ideas and forms, to cultivate the sense of wonder and awe inherent in learning, and to equip participants with the tools to better understand the rewards of closer looking in their own lives. It is, inherently, an argument against the temptation for “distractions,” for “multi-tasking,” and the frenetic pace with which information comes at us and a reminder that the act of looking at–and truly seeing–an object is itself a reward. Slow and close looking quiets the mind and allows for those transcendent experiences that Joseph Campbell called “a radiance” that holds you in “aesthetic arrest.” It is a reminder that Art and Design are not just pretty things, but necessary things that allow us to move beyond our own thoughts and experiences and connect more fully with each other and the world around us.

In truth, there is no absolute canon that we will look towards to guide us along this path; instead, the objects are selected for their aesthetic qualities, their novel approach to problem solving, or because of the compelling lives of those associated with it. Some choices may be familiar–even obvious–but many, I hope, will be a revelation. The goal is to slow down, to cultivate your inherent curiosity, and to see some great art and design in the hope that–with practice–you’re able to regularly experience those moments of awe and radiance in your own life..

| 1 | Sat., Sep. 9, 2023 | Closer Looking: Sculpture and the Plastic Arts Part One, Power and Ritual Despite their vast aesthetic and material differences, Houdon’s George Washington (ca. 1792), an Assyrian Lamassu, and an exceptional headcrest by the Ejagham people (ca. 1900) each function in very similar ways. All share a common language of power and ritual that makes the experience of viewing them transcend conventions of location or era. This session looks closely at ten objects of different times and places to explore the rhetoric of power that sculpture traffics in. |  Asikpo Edet Okun of Ibonda (attr.), headcrest, ca. 1875-1925. Dallas Museum of Art. Asikpo Edet Okun of Ibonda (attr.), headcrest, ca. 1875-1925. Dallas Museum of Art. |

| 2 | Sat., Sep. 16, 2023 | Closer Looking: Sculpture and the Plastic Arts Part Two, Small Things Considered Eschewing the notion that size is necessary to captivate an audience, small sculptural works encourage a sense of intimacy and connection that sculptors have used to illustrate all aspects of life–both sacred and profane–from the earliest times until today. Their very portability made them easier to transport, which in turn made them far more likely to spread ideas and knowledge than their larger, stationary counterparts. From the Woman of Willendorf to an 18th century nativity scene made in Manilla and Ecuador, we’ll explore the intimate space of small sculpture throughout time. |  Adam Lenckhardt, Descent from the Cross, 1653. The Cleveland Museum of Art. Adam Lenckhardt, Descent from the Cross, 1653. The Cleveland Museum of Art. |

| 3 | Sat., Sep. 23, 2023 | Closer Looking: Sculpture and the Plastic Arts Part Three, A World of Pure Form Formalism–the idea that aesthetics matter more than content–is a peculiarly 20th century notion that gives formal analysis of works a bad name. This session explores works through the lens of form, not to avoid or deny content–which is frankly impossible if not highly problematic–but to look at how throughout history sculptors exploited the three-dimensionality of their medium and often maximized the visual impact for the viewer as a result. As is typical, we will wander across space and time with little concern for conventional boundaries exploring ten objects by diverse artists like Louise Nevelson, to an anonymous Angkor period Cambodian artist, to Constantin Brancusi. |  Louise Nevelson, Sky Cathedral, 1958. Buffalo AKG Art Museum Louise Nevelson, Sky Cathedral, 1958. Buffalo AKG Art Museum |

2023

Becoming Stickley

These five sessions take a deep dive into the formative period in Gustav Stickley’s career and explore the choices and decisions that marked his transformation as a designer over his early Arts and Crafts period. Starting in 1900, when he issued the catalog New Furniture from the Workshop of Gustave Stickley and ending with the standardized aesthetic of 1904’s Cabinet Work from the Craftsman Workshops: Catalogue D, we will move year by year through this early work to better understand the how he resolved the competing impulses of historicism and innovation to make him a leading American producer of this new style. Like Stickley, we will navigate the ideals of pure design–unfettered by economic realities–against the realities of running a factory, securing the necessary labor, and making objects that balanced the movement’s idealism with modern consumer preferences. By looking at the paths he chose–as well as those avenues he abandoned–we will arrive at a better understanding of Stickley’s history, his aesthetic, and how the movement flourished in the early twentieth century.

| 1 | Sat., Oct. 21, 2023 | While many point to 1900’s New Furniture from the Workshop of Gustave Stickley as heralding a new commitment to the aesthetic and ideals of the Arts and Crafts movement, this is a notion that relies exclusively on hindsight rather than careful consideration of the forms he made. In many ways, this session argues, the catalog is a perfect illustration of a man conflicted, torn as it were between the thrill of the new and the comfort and security of the past. Moments of radical innovation in the catalog sit along side the Jacobean revival, Japoniste, historicist, and floral forms he created. This catalog–rather than showing he leapt into the Arts and Crafts fully formed–demonstrates a kind of restless curiosity indicative of a man searching for his own aesthetic. |  Workshop of Gustave Stickley, Damascus Plant Stand (no. 9), designed 1900. The Robert Kaplan Collection. |

| 2 | Sat., Oct. 28, 2023 | 1901 was a critical year in Stickley’s development that saw him rename his from “The United Crafts,” exhibit at the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo, begin publication of The Craftsman, and issue at least two additional catalogs and a set of retail plates. While the absence of floral tables and historicizing designs that filled much of the New Furniture catalog indicate a real change in aesthetic, this is largely rhetorical. For while Stickley no longer promoted them, customers continued to order them (and the factory continued making them) through at least 1904. The picture of Stickley that emerges is not one of a radical making a clean break with his past, but instead of a practical businessman who promotes his new designs without alienating the customer base that preferred his older ideas. This year also signaled the earliest iterations of some of his most enduring forms that were gradually refined in later periods. |  United Crafts, Small Rocker (no. 2609), designed 1901. The Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms. |

| 3 | Sat., Nov. 11, 2023 | One of the themes inherent in the broad arc of Stickley’s development is a move away from eccentric experimentation towards a standard, recognizable aesthetic. Especially evident in the forms photographed for The Craftsman and 1902 retail plates, there is an emphasis on solidity, massiveness, and heft that is seen across the forms. While we often think of this as essentially an aesthetic unity, we can be somewhat blind to the efficiencies this created within in the factory and the potential for cost-savings this engendered. That Stickley, ever mindful of both, chose this year to invest in a dovetailing machine is indicative of precisely how he sought to navigate the tensions inherent in creative work in a factory setting. This session explores these forms and ideas and takes a broad view of standardization that encompasses the aesthetic choices and the practice of making furniture to form a richer history of how Stickley’s aesthetic emerged. |  United Crafts, Paper Rack (no. 551), designed 1902. Sotheby’s. |

| 4 | Sat., Nov. 18, 2023 | Stickley’s transformation from a chairmaker to tastemaker is both remarkable and unexpected, since there is little in his history that previously pointed this direction. Yet, by 1903, he seems to have realized that while The Craftsman may not have been the vehicle for social and political change that Irene Sargent dreamed of, it could become a source for ideas about interior design, accessories, and even architecture. Freshly back from his trip to Europe, he mounted an Arts and Crafts exhibition in Syracuse and Rochester that explored these new potentials, and signaled a shift away from simply furniture and embraced the home as a work of art. It is during this year too that major developments in his textiles, metalwork, and furniture take hold and embrace a more graceful, less severe line. This session is a deep dive into 1903, beginning with his Arts and Crafts exhibition and ending with the emergence of inlaid furniture. |  Craftsman Workshops, Five Light Electrolier (no. 223), designed 1904. Rago Arts and Auction. |

| 5 | Sat., Dec. 2, 2023 | By 1904, Stickley had come into his own and issued Cabinet Work from the Craftsman Workshops: Catalogue D, his largest catalog to date that featured over 170 forms. In addition, that year’s What is Wrought in the Craftsman Workshops–published under the auspices of the “homebuilders club”–emphasized his desire to succeed as a tastemaker, the head of a firm capable of designing and building your home and supplying the interior furnishings and accessories. Here too, we witness the result of the fervent experimentation that marked the previous years into a refined style that preserved some earlier forms and made them more efficient to make and market. This year marked the beginning of a decade remarkable for its aesthetic and financial stability, something that had previously eluded Stickley as a chairmaker. |  Craftsman Workshops, Magazine Stand (no. 72), designed 1904. Toomey & Co. |

2022 Online Class Archive:

Close Looking: Design is 2-part, 24 session, online course with Instructor, Dr. Jonathan Clancy, Director of Collections and Preservation.

Part 1: 15 sessions; Recorded Jan. 22 – May 21, 2022.

Part 2: 9 sessions; Recorded Sept. 10 – Nov 19, 2022.

“Close Looking: Design” is an exploration of great design and the process of looking by thinking through those moments in human history when different leaps–whether aesthetic or technological or historical–helped define our built environment. Great design, it turns out, is not confined to a moment or a location. It is found in the subtle arrangement of forms that causes what James Joyce described in his Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man as an aesthetic arrest, a moment in which “the mind… is raised above desire and loathing.” The second cluster of topics in this series aims to explore those moments.

Divided into either forms (like case furniture or tables) or materials (like textiles) these sessions provide a deeper look into the aesthetics of objects, which in turn sheds light on the history of design. In each hour-long session we will look closely at ten objects and think through them to see and understand the pieces in a new way. The goal of the series is twofold: first, to understand the process of choices designers make and the impact these have on the audience, and secondly, to witness the broader sweep of history and the manner in which it continues to shape design.

In truth, there is no absolute canon that we will look towards to guide us along this path; instead, the objects are selected for either their aesthetic qualities or their novel approach to problem solving. You may find some choices familiar (or even obvious) while others will be a revelation. The goal is to get you to look more closely and think more carefully about function and aesthetics, while expanding your knowledge of design history from the distant past to the present day.

2022 – 1.

Close Looking: Design — PART 1

| 22.1.01 | Sat., Jan. 22, 2022 | Chairs and Seating (Part One) |  Cobra chairs by Carlo Bugatti, 1902. Courtesy Sotheby’s. |

| 22.1.02 | Sat., Jan. 29, 2022 | Chairs and Seating (Part Two) |  Joris Laarman, Bone Chair, ca. 2007, courtesy of Sotheby’s. |

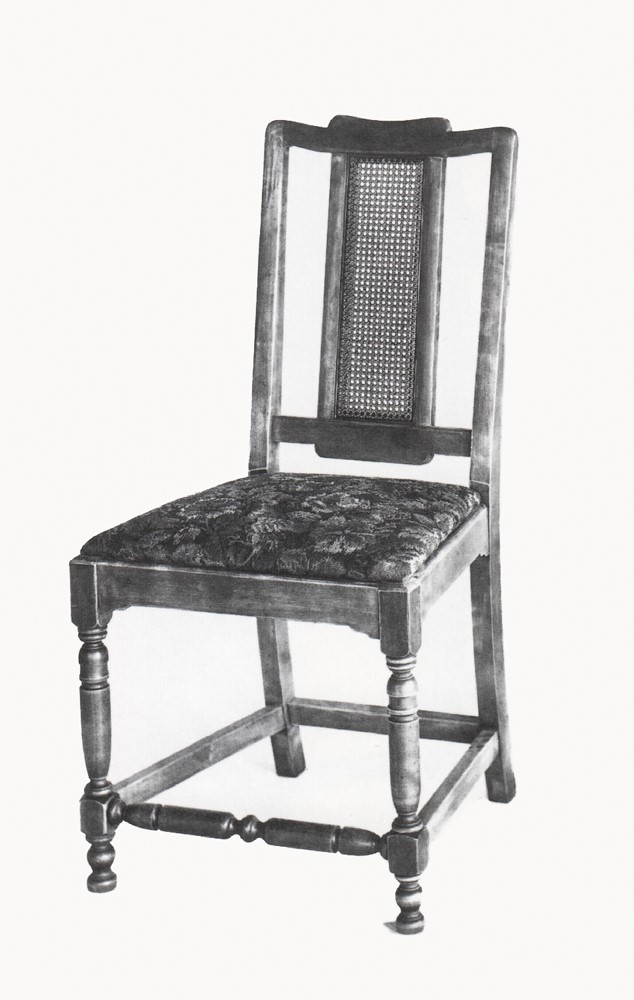

| 22.1.03 | Sat., Feb. 5, 2022 | Great Seating of the Arts and Crafts Movement |  The Craftsman, December 1913 |

| 22.1.04 | Sat., Feb. 12, 2022 | Pottery, the Gift of the Earth (Part One) |  Detail, Cooking Vessel (japanesse, Jomon period), ca. 2,500 BCE. Earthenware, 24 inches. Courtesy Cleveland Museum of Art. |

| 22.1.05 | Sat., Feb. 26, 2022 | Pottery, the Gift of the Earth (Part Two) |  Detail, Judy Chicago, Study for Virginia Woolf from “The Dinner Party,” 1978. National Museum of Women in the Arts. |

| 22.1.06 | Sat., Mar. 5, 2022 | Masterworks of American Art Pottery |  View of Newcomb College workshop, undated. |

| 22.1.07 | Sat., Mar. 19, 2022 | Glass, Clearly and Otherwise (Part One) |  Detail of Dragon-Stem Goblet or Wineglass (Venice), ca. 1630-70. Corning Museum of Glass. |

| 22.1.08 | Sat., Mar. 26, 2022 | Glass, Clearly and Otherwise (Part Two) |  Beaker with Apes (detail), ca. 1425-50. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 22.1.09 | Sat., Apr. 2, 2022 | American Glass from Caspar Wistar to Toots Zynsky |  American Flint Glass Manufactory (attr.), pocket bottle, ca. 1764-70. Yale University Art Gallery |

| 22.1.10 | Sat., Apr. 9, 2022 | Metal Masterpieces (Part One) |  Detail, Adam and Eve reproached by the Lord, 1015. Bronze. St. Michael’s Church, Hildesheim, Germany. |

| 22.1.11 | Sat., Apr. 23, 2022 | Metal Masterpieces (Part Two) |  Art Smith, Necklace, ca. 1958. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. |

| 22.1.12 | Sat., Apr. 30, 2022 | Heavy Metal from the Arts and Crafts Movement |  Karl Kipp, Fern Dish, ca. 1914. Private Collection. |

| 22.1.13 | Sat., May 7, 2022 | Important Rooms and Spaces (Part One) |  The Amber Room, ca. 1701-07. Destroyed in World War II. |

| 22.1.14 | Sat., May 14, 2022 | Important Rooms and Spaces (Part Two) |  The Alhambra, ca. 1238-1358. Granada, Andalusia, Spain. |

| 22.1.15 | Sat., May 21, 2022 | Great Rooms of the Arts and Crafts Movement |  Mackay Hugh Baillie Scott, Main Hall of Blackwell, designed 1898-1900. Bowness-on-Windmere, Cumbria, England. |

2022 – 2.

Close Looking: Design — PART 2

| 22.2.16 | Sat., Sept. 10, 2022 | Case Furniture (Part One) |  John Makepeace, “Flow” Cabinet, ca. 2010. Courtesy of the artist. |

| 22.2.17 | Sat., Sept. 17, 2022 | Case Furniture (Part Two) |  Cabinet (Peru), Late 18th or early 19th century. Museum of Fine Arts Boston. |

| 22.2.18 | Sat., Sept. 24, 2022 | Case Furniture Part Three: Design in American Life |  United Crafts / John Siedemann, Linen Press, ca. 1903. Dallas Museum of Art. |

| 22.2.19 | Sat., Oct. 1, 2022 | Textiles and the Fiber Arts (Part One) |  Tunic with Confronting Catfish (Peru, Nasca-Wari), ca. 800-850. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 22.2.20 | Sat., Oct. 15, 2022 | Textiles and the Fiber Arts (Part Two) |  Annie Mae Young, Work-clothes quilt, 1976. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 22.2.21 | Sat., Oct. 22, 2022 | Textiles, Fiber Arts, and the Arts and Crafts in America |  Harriet Joor for Craftsman Workshops, table runner, ca. 1905. Rago Arts and Auction. |

| 22.2.22 | Sat., Oct. 29, 2022 | Tables and Stands (Part One) |  Table (Italian, Rome), ca. 1775-80. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 22.2.23 | Sat., Nov. 12, 2022 | Tables and Stands (Part Two) |  Joris Laarman, prototype for “Bridge” table, ca. 2015. |

| 22.2.24 | Sat., Nov. 19, 2022 | Tables and Stands Part Three: American Design |  Craftsman Workshops, custom Director’s Table, ca. 1905. Sotheby’s. |

2021 Online Class Archive:

2021 Online Class Archive includes two series:

“Design & History” Online Class Archive (23 sessions in 3 parts, Jan 23 – Aug 28, 2021)

“Circa 1917″ Online Class Archive (5 sessions, Oct. 9 – Nov. 6, 2021)

Design & History: The Past is Always Present

is a 3-Part, 23-session, Online Course with Instructor, Dr. Jonathan Clancy, Director of Collections and Preservation.

Part 1: 6 Sessions; Recorded Jan 23 – Feb. 27, 2021

Part 2: 9 Sessions; Recorded March 27 – May 22, 2021

Part 3: 8 Sessions; Recorded July 10 – August 28, 2021

Design & History: Overview

Writing in 1841, Ralph Waldo Emerson recorded one of the immutable laws of the creative process: “the new in art is always formed out of the old.” So while the Arts and Crafts movement appeared to be a new direction in design, it was indebted to the precedents of our collective past, the shared history of design that was understood amongst its manufacturers, designers, and fiercest advocates. This series seeks to recapture those precedents, not to dilute the importance of the movement, but to better understand it, to wrap it properly in the context of the histories from which it emerged so that its contributions – and the meanings which these objects held to contemporaries – become clearer. Explored in this manner, design is not only practical, but metaphorical, lyrical, and poetic. It speaks to us in the hushed and reverent tones of our shared experiences if we can learn to listen to and discern those muted murmurs.

As author L. P. Hartley cogently noted in his novel The Go-Between: “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” In the final part of the Design & History series we visit those foreign countries, diving deeply into the modern era, examining the pasts that continue to shape our world, and exploring the legacy of, and reaction to, the Arts and Crafts Movement. Starting with Peter Behrens and the birth of industrial modernism, we move through the major movements and figures of the first half of the twentieth century–The Bauhaus, Le Corbusier, Art Deco, and Mid-Century Modernism–before ending at Black Mountain College and the avant-garde.

2021 – 1.

Design & History: The Past is Always Present — PART 1

| 21.1.01 | Sat., Jan. 23, 2021 | Reimagining the Gothic: Roots of a Revolution There is no period more appropriate to begin the historical precedents of the Arts and Crafts movement than the Gothic, a new expression of religious sentiment that flourished in Europe during the 12th to 15th centuries. It provided – for the Pre-Raphaelites, English reformers, and American exponents – a perfect metaphor for their renewed commitment to craft and came to stand as the last moment of pure sincerity in a world that became increasingly illusionistic and insincere since the Renaissance. From the rise of the movement’s broader acceptance in the 12th century to its height in the 14th century, we explore the meaning of the Gothic, review the forms and terms you’re likely to encounter, and discuss its impact in the late 19th century. |  Rose Valley, Library Table, 1904. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 21.1.02 | Sat., Jan. 30, 2021 | East Meets West: The Birth of Global Design Western fascination with the Asian aesthetic exploded in the 17th century, as the formation of the Dutch East India Company in 1602 expanded commercial activity and brought sustained contact with Asian objects to increasing numbers of consumers. Throughout the 17th century, this radically changed the course of design history as the Chinese taste forced European manufacturers to adapt their own wares to these latest styles. The chinoiserie, japonisme, and orientalism that flourished from the 17th to 19th centuries (and which many in the Arts and Crafts movement were indebted to) began here. The dialog between the East and West was amongst the earliest manifestations of globalism that continues to shape our aesthetic in the modern era. |  Chelsea Keramic Art Works, Vase, ca 1885-89. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 21.1.03 | Sat., Feb. 6, 2021 | Drama, Design, and Deposed Rulers: William and Mary as Tastemakers From the late 17th century to the 18th century, Europe was spellbound by the rise of William and Mary, the son-in-law and daughter of James III who deposed the English King and ruled as joint sovereigns until her death from smallpox at age 32. Cosmopolitan and wealthy, the couple’s reign marked a period of aesthetic innovation that saw the rise of Japanning (a technique by European furniture makers to imitate Asian lacquerware) and increased dispersion of skills between continental craftsmen and their English counterparts. Following William’s death in 1702, his sister-in-law, Queen Anne ascended to power and continued the transformation of the Western aesthetic, overseeing a period that became more graceful and less rectilinear. These styles were ones that Stickley returned to early (and later) in his career, hoping to capitalize on the rising tide of the Colonial Revival aesthetic and the associations of honesty, craftsmanship, and good design with which Americans imbued these movements. |  Gustav Stickley, The Craftsman, Side Chair, ca. 1915-17. |

| 21.1.04 | Sat., Feb. 13, 2021 | Somewhat Naughty, Frequently Haughty, and Occasionally Bawdy: The Rise of the Rococo If you listen closely, you might here the indignant question: “What does the Rococo have to do with Stickley, in particular, or the Arts and Crafts, in general?” The answer is really twofold. First, Stickley’s revival furniture of the 1890s and later 1910s relied heavily upon the “Chippendale,” the English manifestation of the movement named for the celebrated cabinet-maker. Second, as Emerson reminded us in “Art,” “the very avoidance betrays the usage he avoids.” For Stickley–like many in the Arts and Crafts–the Rococo served as inspiration and foil, it was powerful, almost talismanic; it simply could not be avoided. Beginning with career of Watteau (ca. 1710), the Rococo was everything the Baroque could never be: light, playful, sin-filled, and curvaceous. It was an era of increased trade with colonies in the Americas, which gave rise to the increasing use of mahogany and other exotic materials. It was so popular in fact, that after going out of style by 1800, it was revived by the 1840s, and formed the foundation for much of the Colonial Revival aesthetic. |  Gustave Stckley Co., Arm Chair (no. 263-A), ca. 1898-1903 |

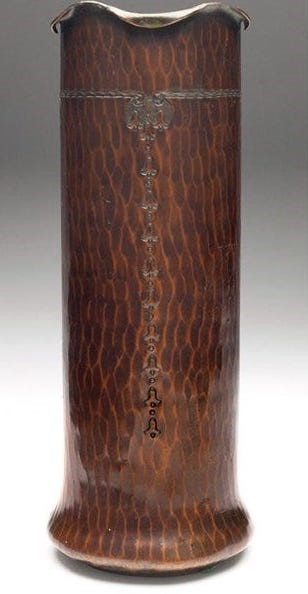

21.1.05 | Sat., Feb. 20, 2021 | The Apotheosis of Neoclassicism (or How the West got Serious Again) Since the rediscovery of Pompei and Herculaneum in the early 18th century, Europe was enthralled with classicism, a sensation that finally became full-blown in the late 18th century. From the paintings of Jacques-Louis David to the ceramics of Wedgwood to the furniture of Sheraton, there was a flourishing neoclassicism that swept across Europe and became the dominant style at the beginning of the 18th century. Eschewing the frivolity and playful fun of Rococo excess, this was a serious style whose gravitas was conveyed by restrained lines, gentle curves, and the return of symmetry. Gone were the nude maidens of Boucher frolicking in the waves, replaced instead by the imagined past of classical times–urns, garlands, myths, and bellflowers, rigid and unwavering in their precision, became the preferred decorative scheme. |  Roycroft Shops, Vase (no. 213), ca. 1918. Treadway Toomey Auctions. |

| 21.1.06 | Sat., Feb. 27, 2021 | You Are What You Eat: Food, Globalism, and the Transformation of Design It is difficult to fully appreciate that the simple pleasures we take for granted today–coffee, tea, and chocolate–were extravagant novelties that transformed the world of material culture (and culture in general) by their introduction. Simply put: new foods called for new forms. The consumption of these goods engendered new rituals that changed how we interacted, what we needed to interact, and the very spaces in which we interacted. Globalism, and in particular the new commodities it brought into the western palate, meant the introduction of forms–from spice mills to sugar boxes to tea pots and tea tables–that were previously unimaginable as a part of daily life. This session explores the transformation of design–not as an aesthetic phenomenon–as a need-based reaction to a world struggling with how to make sense of globalism and to domesticate its benefits into the rituals of consumption. |  Charles Rohlfs, The Rohlfing Dish, 1904. Toomey & Co. Auctioneers. |

2021 – 2.

Design & History: The Past is Always Present — Part 2

| 21.2.01 | Sat., March 27, 2021 | A More Muscular Classicism: The Western World in the Early 19th Century At the end of the 18th century, when Europe was consumed by a delicate neoclassicism that presented an austere sense of order in contrast to the sinewy, riotous curves of the Rococo, new ideas were afoot. Gradually, the delicacy of the late-eighteenth century gave way to a classicism that was bold, muscular, and imposing. Known by different names throughout Europe and the United States, the Empire or Biedermeier style took the vocabulary–the building blocks–of classicism and reconfigured them into a distinctly different approach to design that shaped design over the following decades. |  Fall Front Desk (Vienna), ca. 1810. Various woods and gilt bronze. Art Institute of Chicago. |

| 21.2.02 | Sat., April 3, 2021 | Egypt and Egyptomania Following Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt at the turn of the nineteenth century, Western decorative arts experienced their first profound wave of Egypto-mania, relishing in the exoticism of a distant past and mystical land. Pyramids, sphinxes, and papyrus leaves began to appear on designs on furniture, ceramics, and architecture across Europe and the United States, fueled by scientific exploration and the publication of findings. By the 1820s, scholars had begun to decipher the Rosetta Stone, which made a past that had been previously lost to time suddenly decipherable. This session explores the aesthetics of Egyptian art and architecture that Europeans encountered, and examines how these impacted design and decoration in the 19th century, from Wedgwood to the Herter Brothers. |  Pottier and Stymus (attr.), table, 1870-75. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 21.2.03 | Sat., April 10, 2021 | Greek Arts and The Greek Revival While the discoveries of Pompeii and Herculaneum captured the imagination of 18th century designers, a quiet revolution was brewing, one that would look back further in antiquity to prize the quiet grandeur of all things Greek to the excessive exuberance of Roman design. In this session, we move again in two directions: back to the Greeks to understand the essential aesthetics that shaped their particular contributions to Western art history, and into the 19th century where a revival of these ideas spurred advancements in architecture and design in Europe and the Americas. By looking closely at Greek art and architecture, we’ll see another side of the many classicisms that were available to 19th century designers and witness how these masterpieces of antiquity were updated for modern life. |  Duncan Phyfe, Couch, ca. 1837. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

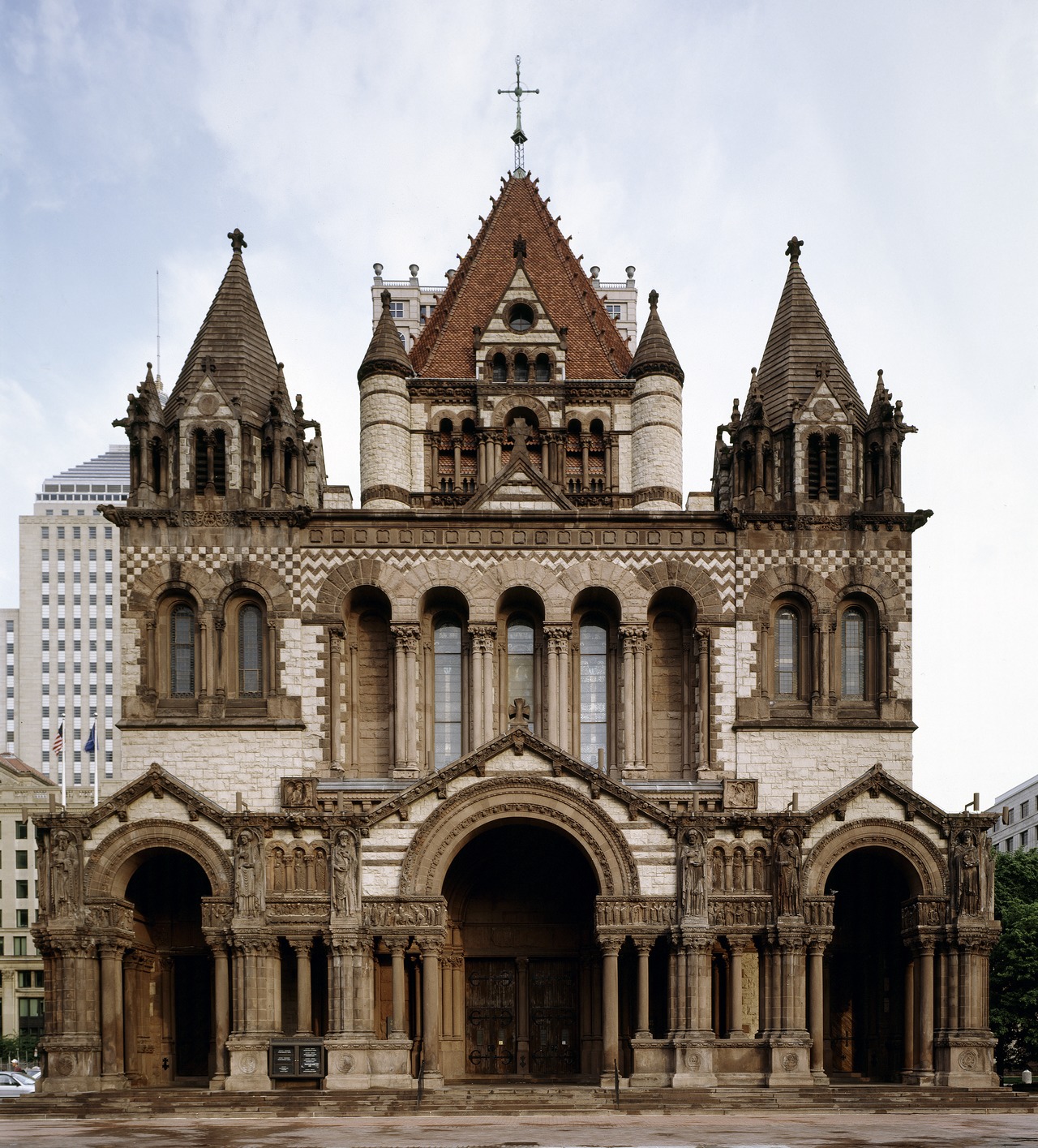

| 21.2.04 | Sat., April 17, 2021 | Romanesque, the Romanesque Revival and Henry Hobson Richardson Eschewing the fancy marbles and high-style of the Greek Revival and other classicisms, Henry Hobson Richardson created an alternate type of historicism in the late 19th century that preserved the grand scale of those other styles but spoke to the rustic handwork that was increasingly prevalent. Known today as Richardson Romanesque–and perfectly illustrated by his masterwork Trinity Church in Boston–Richardson drew upon European architecture of the pre-Gothic period to create his bold vision. This session will explore not only the major works of this style in depth, but look too at the origins of this movement–the Romanesque period–to better understand the aesthetic Richardson helped shape by looking at what he preserved and ignored from our collective past. |  Henry Hobson Richardson, Trinity Church, 1872-77. Boston. |

| 21.2.05 | Sat., April 24, 2021 | Pugin and the 1851 Crystal Palace Exposition While the 19th century was marked by an exuberance for technological advancements, there was still more than enough anxiety about the changing world to go around. As the first World’s Fair celebrated humanity’s progress, it was marked too by the desire to return to the simplicity of the middle ages most forcibly stated by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin’s Medieval court exhibited in the Crystal Palace. This session explores the critique of modernity that flourished in the wake of this exhibition covering such well-known names as John Ruskin and William Morris, but giving proper credit to Pugin whose 1836 publication of Contrasts in 1836 would set the stage for the medievalizing fantasies of subsequent design reformers and critics of modernity. |  View of the Crystal Palace, ca. 1854. |

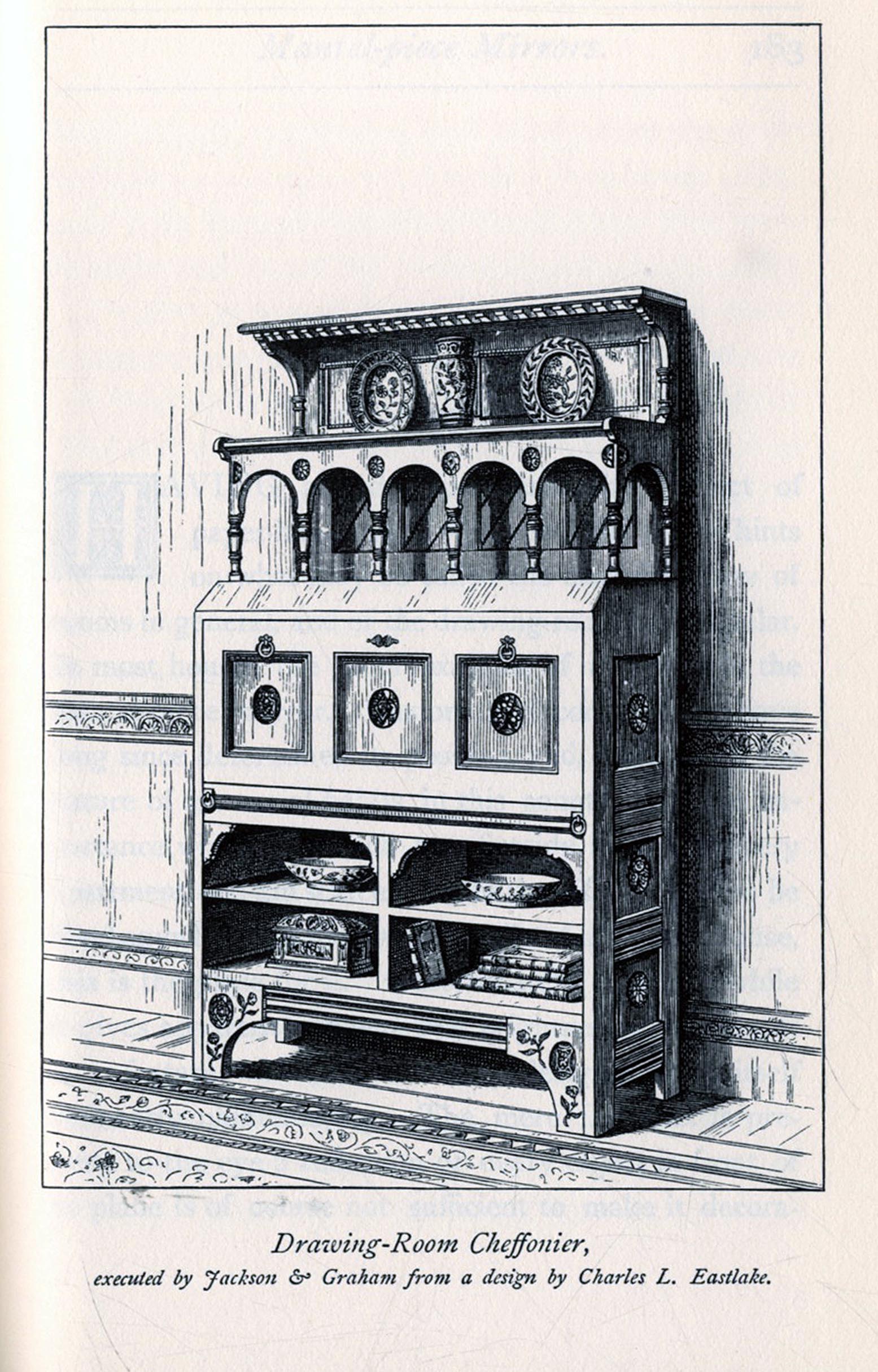

21.2.06 | Sat., May 1, 2021 | Charles Eastlake and Design Reform in the Late 19th Century It is difficult to underestimate the impact of Charles Eastlake’s Hints on Household Taste in Furniture, Upholstery and Other Details published in England in 1868, then in the United Sates in 1872. With a focus on the middle class as opposed to the monied elite, Eastlake’s influence was immediately felt through attractive furniture that he claimed could be mass-produced “as cheap as that [furniture] which is ugly.” In the United States, where his book underwent six printings, his ideas impacted furniture design, architecture, and came to epitomize what we think of as “Victorian” today. And yet, a close reading of Eastlake reveals not the polar opposite of the Arts and Crafts movements as we sometimes think, but surprising through lines and connections. |  Drawing Room Chiffonier, designed by C. L. Eastlake. |

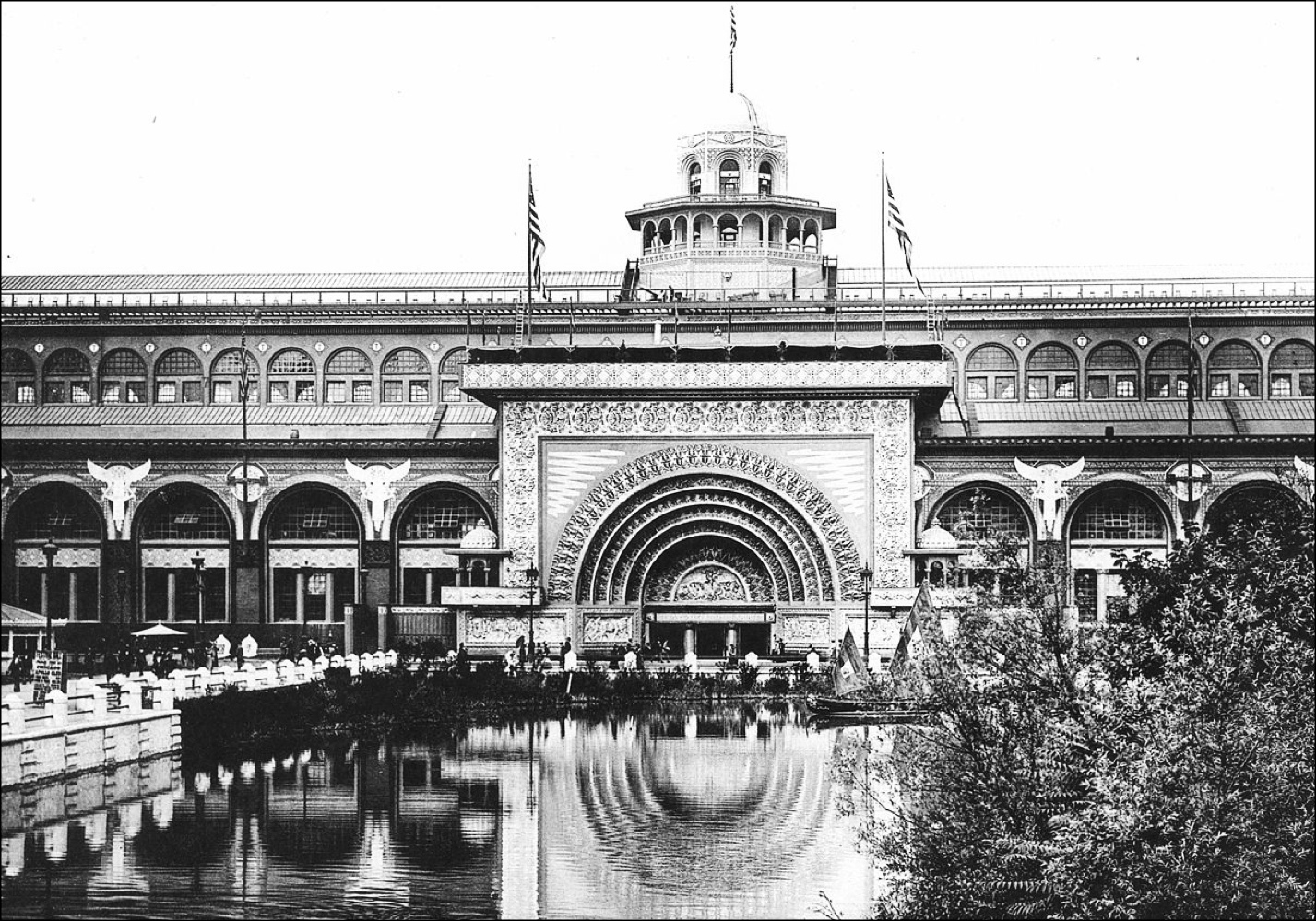

| 21.2.07 | Sat., May 8, 2021 | Classical Splendor in the Modern World: The White City and the Columbian Exposition In the same decade we witnessed the rise of the Arts and Crafts, the Prairie School, Colonial Revival, and Art Nouveau movements, Chicago’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 saw “the White City” emerge from the shores of Lake Michigan to transform American civic design and help spur the City Beautiful movement. If the late 19th century saw an increase in the speed with which change occurred and styles changed, Classicism provided a sense of stability and permanence. Bringing together luminaries like Frederick Law Olmsted, Lorado Taft, and Daniel Burnham the Exposition’s aesthetic–with the notable exception of Louis Sullivan’s Transportation building–relied upon the precedents taught at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris in the late 19th century. |  Louis Sullivan, The Transportation Building for the Columbian Exposition, 1893. |

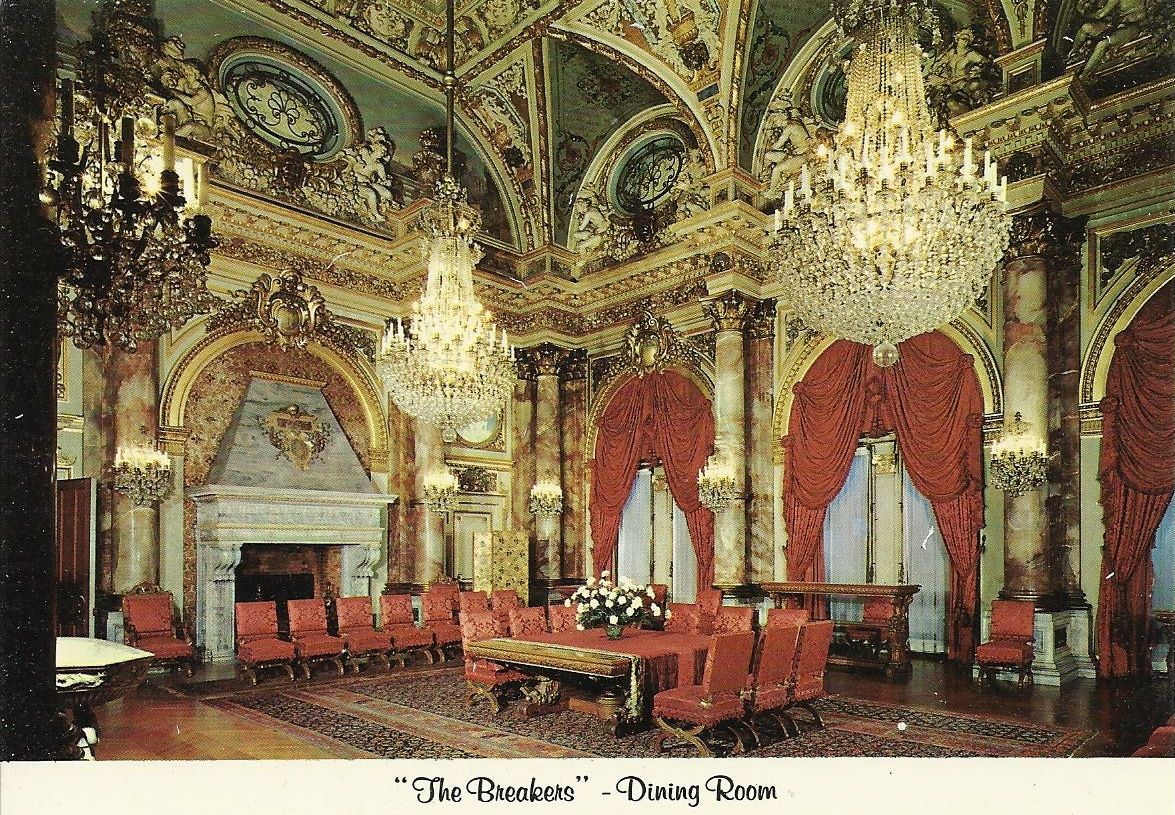

| 21.2.08 | Sat., May 15, 2021 | American Excess: Wealth and Taste in the Late 19th Century At the end of the 19th century, a few citizens of the United States saw a rise in wealth that had previously been the exclusive purview of the nobility. If it was the peculiar circumstances of the American experiment that gave rise to their wealth, it is clear–in hindsight–that their notions of taste were rooted in old world ideas of class, culture, and wealth. This session examines the homes and collections of Isabella Stewart Gardner, Andrew Carnegie, the Vanderbilts, and others to explore how their aesthetics developed and how they continue to impact our understanding of art and architecture today. |  Richard Morris Hunt, Dining Room of the Breakers, 1893. |

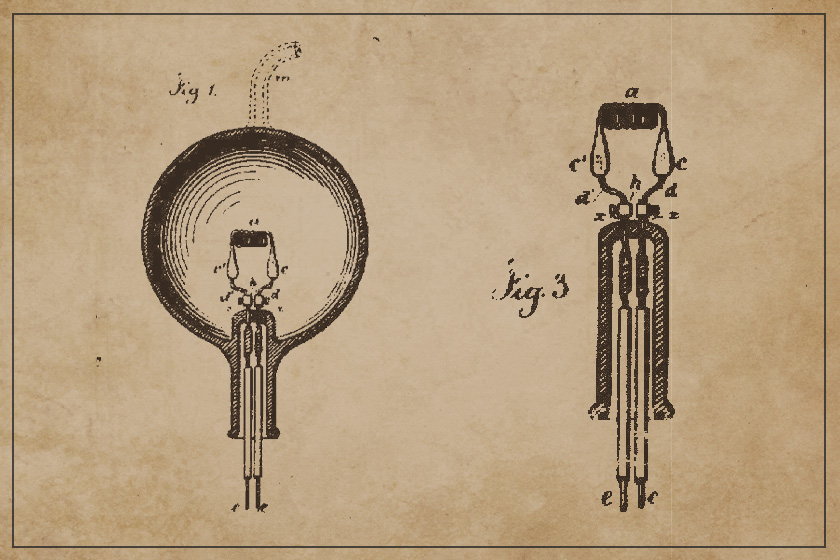

| 21.2.09 | Sat., May 22, 2021 | Technology and the Transformation of the Home In the same way we witnessed how new foods transformed culture in the last series, technology transformed the social structure of the home throughout the 19th century. Advances in lighting, heating, mechanical inventions, and refrigeration throughout this period changed the way we ate, socialized, and used the home. Rather than something fixed, culture–it turns out–is a curious arrangement of pre-existing conditions that is continuously reshaped by the manner in which we assimilate new ideas, new people, and new inventions. It is a reminder too that there is no “American” culture, but rather a series of cultures that simultaneously exist broadly, locally, and always in a constant state of flux. |  Thomas Edison, drawings for an electric lamp, 1880. |

2021 – 3.

Design & History: The Past is Always Present — Part 3

| 21.3.01 | Sat., July 10, 2021 | Peter Behrens and the Birth of Modern Design As we move into the 20th century, my argument for the first session is quite simple: Peter Behrens was a brilliant designer who should be more of a household name. Competent in a number of different styles from Art Nouveau to Industrial design to Classicism and Expressionism, his work as a designer, architect, and teacher / mentor heralds the birth of modernism as a style. Without the pioneering work of Behrens, there is no International Style, no Dieter Rams of Braun, no Mies or Corbusier or Gropius as we know them, since they all worked as assistants in his office. From his AEG Turbine Hall (1909, Berlin) to industrial clock designs, to his Expressionist masterpiece the Technical Administration building for Hoescht, Behrens proved himself able to change with the demands of the times and the mandate he was given, and ranks amongst the most important designers of the twentieth century. |  Thomas Edison, drawings for an electric lamp, 1880. |

| 21.3.02 | Sat., July 17, 2021 | Cubism: The Rise of Geometric Modernism In the first decades of the twentieth century, certain unrelated strains of modernism sprang forth that embraced a fractured, geometric approach to composition best exemplified by the analytical Cubism of Braque or Picasso. And yet, as the Wiener Werkstätte reminds us, these movements predated the very invention of Cubism and certainly its wider distribution. This session explores these trends, looking at varied movements from the Wiener Werkstätte to De Stijl, to Soviet Constructivism and Suprematism, and considers the impulses that were common to that approach, inklings of which were evident in Cezanne’s work by the 1890s. |  Gerrit Rietveld, Red Blue Chair, ca. 1918-23. Museum of Modern Art. |

| 21.3.03 | Sat., July 24, 2021 | Mysticism, Modernism, and Often Misunderstood: The Bauhaus Often thought of as a pinnacle of European modern design, this session explores the Bauhaus from its roots in Henry Van de Velde’s Weimar School for the Applied Arts to its growth under Walter Gropius to what essentially became an architectural laboratory under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe before it was closed in 1933 by mounting pressure from the Nazis. Often overlooked in the Bauhaus history is the persistent influence of Expressionism, mysticism, and the role that handicraft played in the development of the school’s aesthetics. Johannes Itten, a neo-Zoroatrianism, vegetarian, painter, and mystic developed the Basic course of study at the Bauhaus and forms an important counterpoint to the international style that continues to dominate our impression of the movement. Hand weaving, timber structures, pottery making, and embrace of exoticism were essential factors in the development of the Bauhaus. |  Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer, Sommerfeld House, 1920-22. Berlin |

| 21.3.04 | Sat., July 31, 2021 | The International Style Amongst the most recognizable styles of modern architecture and design, the International Style also established the canon of luminaries we continue to revere: Le Corbusier, Mies Van Der Rohe, Marcel Breuer, and Alvar Aalto. Practitioners favored modern materials, balance (as opposed to symmetry), and emphasized the volume of space rather than the mass of the façade. Generally devoid of ornament, part of the appeal of the movement, and indeed its supremacy from about 1930 to the 1980s, was that it was reproduceable ad nauseum anywhere. The unfortunate legacy of the International Style is a staggering amount of non-descript glass and steel buildings all over the world that often distracts from the aesthetic achievements of the movement’s best work. In this session, we will recapture that history, look at what makes for great (and, by contrast, really poor) International Style design, and see the manner in which subtle manipulations of proportion and materials created these iconic structures. |  Le Corbuiser, Pierre Jeanneret, and Charlotte Perrirand, Armchair with tilting back, 1928. Museum of Modern Art. |

21.3.05 | Sat., Aug. 7, 2021 | Can We Make it Jazzier? Art Deco and the Return of Decoration If the International Style was clean and elegant, it was also cerebral and markedly un-fun. Enter: Art Deco, and with that the realization that decoration, historicism, and visual play were satisfying, uplifting, symbolic, and desirable. From Radio City Music Hall to the Chrysler Building to the SS Normandie, high-style Art Deco’s embrace of luxury materials, contrast, pattern, and decoration formed a welcome relief to the somber elegance of the International Style. This session looks at the return of decoration and the movement’s best designs and designers, including Emile-Jaques Ruhlman, Donald Deskey, Viktor Schreckengost, and Ruth Reeves. |  Donald Deskey, Cigarette Box, 1928. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 21.3.06 | Sat., Aug. 14, 2021 | Craft Workshops in an Era of Mass-Production From George Nakashima to Wharton Esherick, from Gertrude and Otto Natzler to Leza and William McVey, the practice of craft and the notion of the individual studio continued to hold sway even as the acceleration of mass production drove designers and producers farther apart. In this hour, we explore the persistence of the artist producer in the modern economy, highlighting works from the artists mentioned above, but looking too at artists like Harvey Littleton, a revolutionary who resisted modern production methods by taking an art that had been confined to larger practices–glass making–and creating a studio practice that rescued craft from industry. |  Wharton Esherick, Desk, 1970. Courtesy of Rago Arts and Auction Center. |

| 21.3.07 | Sat., Aug. 21, 2021 | Design at Mid-Century: Softer Modernisms Moderne, streamlined, biomorphic, mid-century, these terms denote a school of thinking that arose to fill the gap between the austerity of the International Style and the excessive decorative impulses of Art Deco. Exemplified by figures such as Russell Wright, Eva Zeisel, Charles and Ray Eames, and Isamu Noguchi, these designers sought a middle path and chose to preserve the clean lines of modernism while softening its hardest edges. Their efforts and their collaboration with industry put “good design” within the reach of the masses and helped shape the material culture of that period and even into today. |  Eva Zeisel, Town and Country Salt and Pepper Shakers, ca. 1945. Museum of Modern Art. |

| 21.3.08 | Sat., Aug. 28, 2021 | The Black Mountain Legacy: Bauhaus and Beyond With the final closing of the Bauhaus in Berlin in 1933 and the rise of Nazism in Germany, artists and designers–if they were able to–fled. Black Mountain College, in western North Carolina, was the unexpected beneficiary of Germany’s deteriorating political climate as nearly a dozen artists associated with the Bauhaus (including Walter Gropius, Anni and Joseph Albers, and Lyonel Feininger) came to work at the school. Although short-lived–lasting just 24 years from 1933-57, Black Mountain’s impact on American and Art and Design is difficult to overstate: Peter Voulkos, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Willem de Kooning, Jacob Lawrence, and Robert Motherwell all spent time there. So too did Buckminster Fuller, Albert Einstein, and Ruth Asawa. This session explores this amazing moment, the overlap of art / design / dance / craft / engineering and the impact it continues to have on our world. |  Peter Voulkos, untitled, 1957. Courtesy of Cowan’s Auctions. |

2021 – 4.

Circa 1917: Rediscovering Craftsman Farms

Circa 1917: Rediscovering Craftsman Farms is a 5-Part Online Course with Instructor, Dr. Jonathan Clancy, Director of Collections and Preservation.

Circa 1917: COURSE OVERVIEW

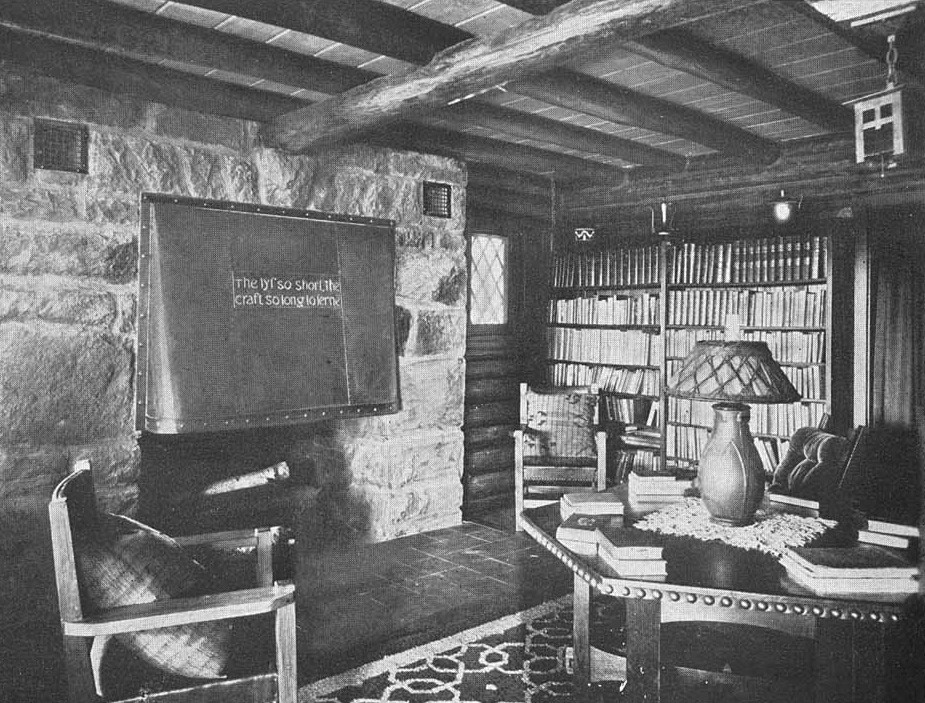

These five sessions compliment the exhibition of the same name and provide a chance to dig deeper into Craftsman Farms as it evolved during the Stickley family’s ownership from 1908-17. Envisioned, at various times, as a school, a working farm, and a country retreat, the property grew to nearly 650 acres during Stickley’s ownership and served as the family’s home. From the landscape, to the buildings, to the furnishings, this exhibition is a comprehensive view of the evolution of Craftsman Farms that brings together our latest research and documentation to provide the most complete picture the Museum has ever offered. Featuring original objects, previously-unknown original buildings, and glimpses into parts of the campus normally unseen by visitors, this series gives audiences a chance to explore Craftsman Farms as an insider, to see it as it stood when the Stickleys departed in 1917. Put simply: whether you are a long-time member who has visited dozens of times or are a new supporter longing to visit, these sessions provide unprecedented access that will allow you to rediscover Craftsman Farms for yourself.

| 21.4.01 | Sat., Oct. 9, 2021 | The Lay of the Land: Understanding the Craftsman Farms Campus The Craftsman Farms we know today bears little resemblance to the project Stickley began in 1908. Nestled amongst suburban development in a densely populated area of Northern New Jersey, the remaining 30 acres continue to serve as an oasis even though they are but a fraction of the 650 acres that Stickley assembled. This session focuses on the campus–how it worked, how it was laid out, and even its development–from 1908 to 1917, discussing the structures Stickley built, those that were extant on the properties when he purchased them, and those elements that have been lost to time and development. The goal is to reorient ourselves to the campus so that we can appreciate the scale and effect that Craftsman Farms had during the Stickley era. |  Stickley children, Gustav, Jr., and one of his sisters from Marion Stickley’s scrapbook. |

| 21.4.02 | Sat., Oct. 16, 2021 | What Remains: Stickley’s Vision at Craftsman Farms Today From furnishings, to structures, to farm equipment and other bits of material culture that have survived for more than a century since the Stickleys sold the property to the Farny family, a remarkable amount of original material remains (or has been returned) to Craftsman Farms, each capable of telling a story about the Stickley era. Whether in pristine condition or obscured through loss and alteration, these objects and buildings are essential to rounding out our picture of life on Craftsman Farms and understanding the scale of the project and the visual world that that the family inhabited. This session includes items new to the collection, previously undocumented furniture, and interiors normally unseen by visitors. |  Southwest corner of the Log House in 1911. |

| 21.4.03 | Sat., Oct. 23, 2021 | Complexity and Contradiction: Furnishing the Log House For over 30 years the focus in the Log House interior of Stickley’s family home has been–quite understandably–on the furniture that Stickley made for the space. Yet, the photographs and archival record point to a richness of color, textures, and makers that have not previously been acknowledged or explored. Indeed, while the image of Stickley we conjure is that of an Arts and Crafts purist dedicated solely to his mission, the visual environment of his home paints a more nuanced and complicated picture that challenges our beliefs and gives us a rare window into his personal tastes. Surprisingly, especially for a man who published a magazine for more than 15 years, Stickley’s inner life–his tastes, persona, and home life–remains opaque and difficult to discern; indeed despite all of the text he wrote, our vision of him is somewhat two-dimensional and flat. Viewing him through the lens collector / decorator / furnisher allows us, for the first time, to flesh out these aspects of his persona that remained carefully apart from his role as a leading voice for the Arts and Crafts movement. |  James Clews, plate, ca. 1818-34. Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh. |

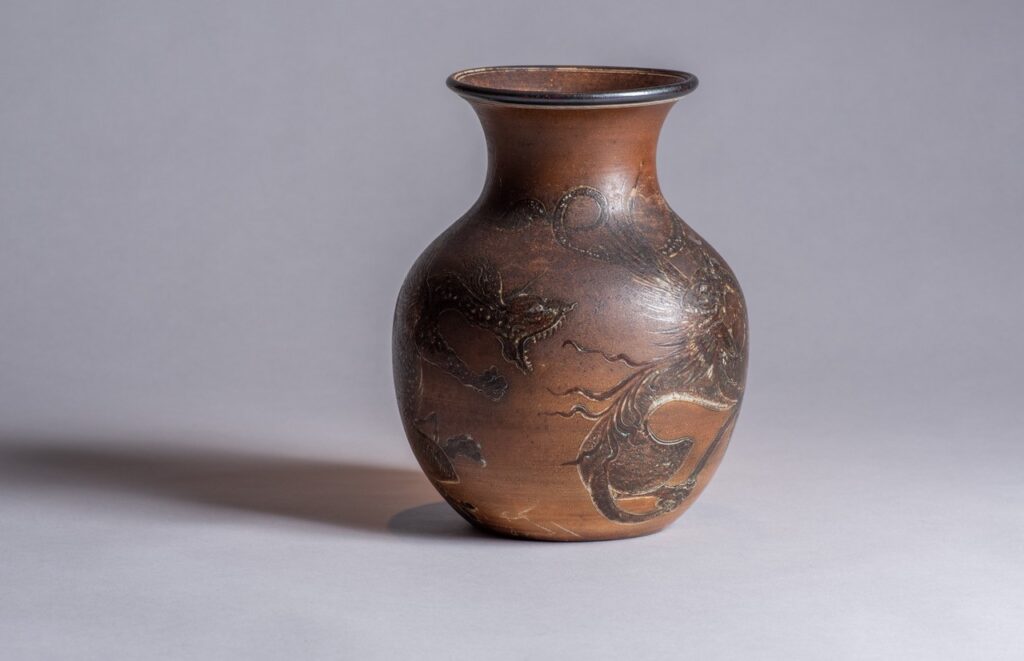

| 21.4.04 | Sat., Oct. 30, 2021 | You Can Take it With You: Selections from Stickley’s Descendants While the early photographs of the Log House are an essential component to understanding the material culture that informed Stickley’s worldview, they are necessarily problematic too. For starters, the photographs published in The Craftsman in 1911 were taken prior to the family’s occupation of the Log House and thus cannot fully capture the home as it was adapted to their lives. Second, these photographs provide us snapshots of a vision from 1911, and they are equally telling in what they do not show, like the kitchen, the porch, three bedrooms and the upstairs hall. Nor do they speak to life within the property’s three cottages or the furnishings contained therein. This session dives deeply into the archival record and selections from Stickley descendants to recapture a sense of the broader Craftsman Farms project that the Stickleys embarked upon. |  R. W. Martin and Brothers, vase, 1893. Collection of Drs. Cynthia and Timothy McGinn. |

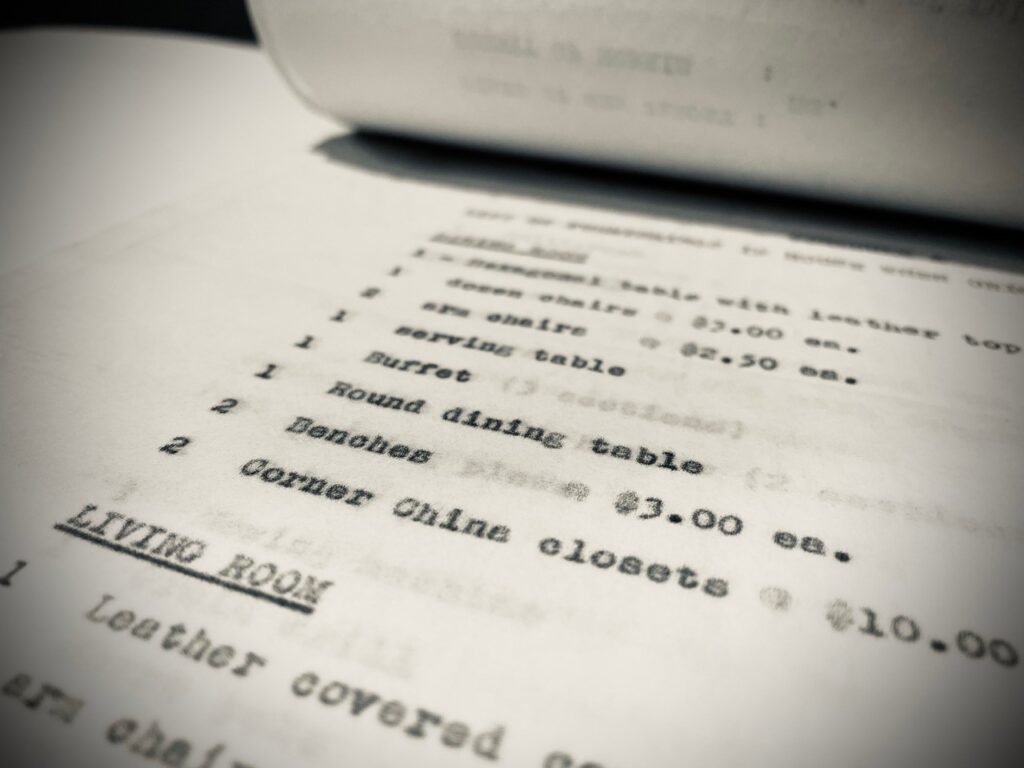

| 21.4.05 | Sat., Nov. 6, 2021 | Making an Exhibition: Conservation and Documentation Exhibitions emerge complete; they open (or are put online) as fully formed entities that have seemingly sprung forth as realized visions from the heads of curators. The reality of exhibition-making is quite different, and this session provides a behind-the-scenes look at the making of Circa 1917. From the conservation of collections objects, to the physical and archival record drawn upon to make this exhibit possible, this is a candid look at the process of research and discovery, focusing on questions such as: what can the objects tell us? How is conservation and restoration decided upon? What does conservation entail (and how can I get my pieces looking better)? And, most importantly: What does research actually entail and how does one go about it? |  Page from the estate tax return of George W. Farny, 1941. |

| 21.4.06 | Sat., Nov. 13, 2021 | Bonus Content *Bonus Content is free for all “Circa 1917” class attendees. (Minimum of one session). |

2020 Online Class Archive:

The 2020 Online Class Archive includes 8 series:

1. Living the Simple Life: The Arts and Crafts Movement at Home

2. ICONS OF 20TH CENTURY DESIGN

3. Craftsman Utopia: Gustav Stickley’s Craftsman Farms

4. “Making Her Mark”: Women in the American Arts and Crafts Movement

5. The Creative Spark: Rethinking Decoration in the Arts and Crafts Movement

6. THE CRAFTSMAN: The Life & Work of Gustav Stickley

7. The Restorative Power of Craft

8. A Very Craftsman Christmas

8. A Very Craftsman Christmas

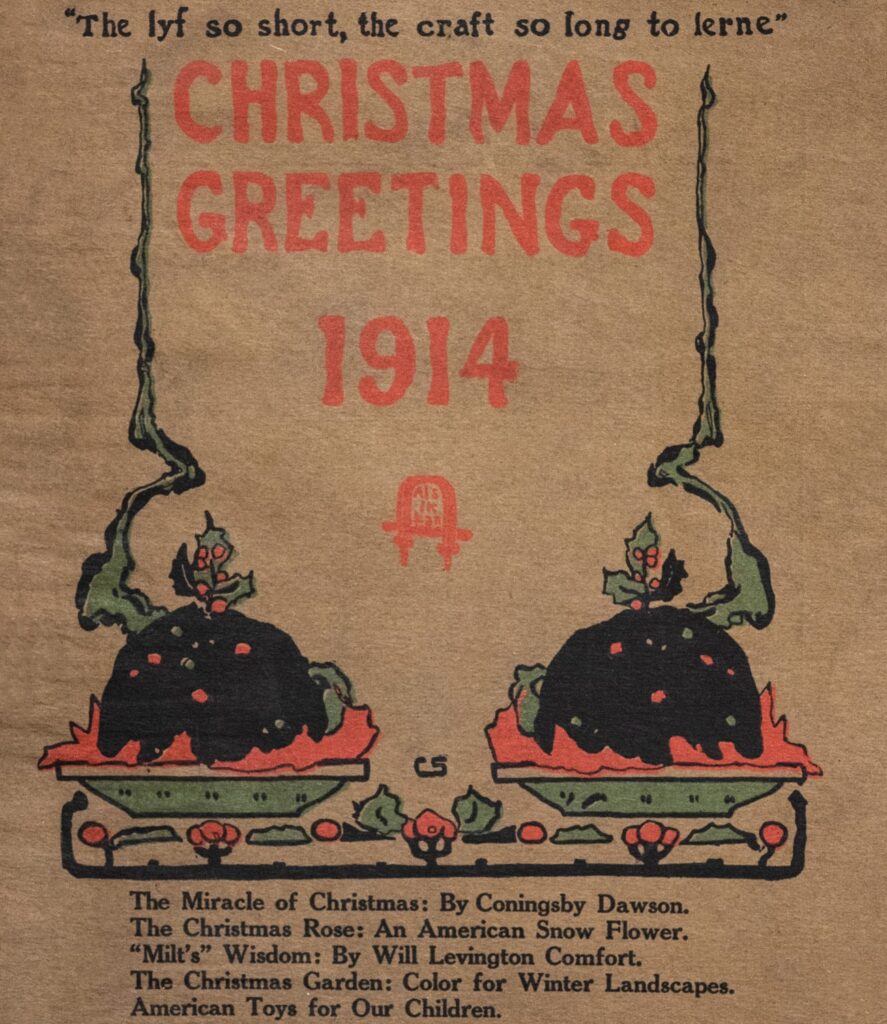

| 8 | Sat., Dec. 19, 2020 | A Very Craftsman Christmas In our final class of 2020, we examine the products and projects that Stickley promoted–from pottery to furniture to hand-made toys–demonstrating the breadth of The Craftsman’s reach and reminding each other that in spite of modernity’s madness we can still find moments of solace, of generosity, and of selfless concern for others. Writing in the The Craftsman in 1904, Stickley opined about the inherent tensions between modernity and the spirit of generosity he believed was inherent to Christmas. “There is little danger,” he wrote, “that the spirit and beauty of Christmas giving will ever be overdone or outgrown, in the truest sense, but there is a danger in an increasing modern tendency to change the ‘blessedness of giving’ into a burdensome obligation, due to social rivalry and other causes, which really have no part in the real spirit of Christmas-tide.” In many ways, Stickley’s struggle with Christmas is a microcosm of the movement’s broader issue, how to balance the spiritual impulse and redemptive nature of craft with the commercial necessities of a business. For the next twelve years, Stickley promoted both sides of this, using the magazine’s content to promote “our better angels” while the back pages–the advertising–suggested last minute-gifts for harried givers. |   |

November/December 2020 series:

7. The Restorative Power of Craft

| 7.1 | Sat., Nov. 14, 2020 | Session 1: Working Their Way Back to Health: Marblehead Pottery Anxiety is inextricably linked to modernity. Humanity fretted and suffered as we sought to figure out how to navigate a world in which labor, markers of wealth, and long-held beliefs about our place in the universe seemed to be challenged and upended almost daily. Founded about 1904 by Dr. Herbert Hall of Boston, the pottery was part of a broader experiment to use the handicrafts therapeutically as a “work cure” to alleviate the nervous ailments of modern life. Soon professionalized under the leadership of Arthur Baggs, Marblehead became one of the leading producers of Art Pottery in the United States that subtly shifted the equation of “production-as-therapeutic” to emphasize the value of a quiet, restorative aesthetic to consumers seeking to buttress their homes from the disquieting influences of modern life. |  Marblehead Pottery, vase, c. 1909. Glazed earthenware, 8 1/2 × 6 7/8 × 6 7/8 in. Image courtesy of the Art Institute of Chicago. |

| 7.2 | Sat., Nov. 21, 2020 | Session 2: Within the Shadow of a Great Scourge: Tuberculosis, Van Briggle, and Arequipa Pottery Prior to the development of an effective vaccine and antibiotics, Tuberculosis was a virtual death sentence. Like every segment of the American population, the Arts and Crafts movement was impacted by the disease, and while the results were predictably dire for those infected, the disease and the movement’s response to it left a complex legacy that included artistic and creative triumphs alongside these tragedies. Indeed, it is hard to imagine the existence of either the Van Briggle or Arequipa potteries separate from the “shadow of a great scourge” as it was described in the Brick and Clay Record in 1915. This session delves into the work of the Van Briggle and Arequipa potteries, both of which were formed as a response to the pandemic. |  Van Briggle Pottery, vase, 1903. Glazed stoneware and bronze, 11 inches. Image courtesy of Rago Arts and Auction Center. |

| 7.3 | Sat., Dec 5, 2020 | Session 3: Making Pots and Useful Citizens: The Saturday Evening Girls Founded in 1908 under the patronage of Helen Osborne Storrow and guided by the visions of Edith Guerrier and Edith Brown, the Paul Revere Pottery in Boston sought to provide immigrant girls a means of making a living and acculturating them to the attitudes and history of the United States. With over 13 million immigrants accounting for more than one-sixth of the American population by 1910, the pottery was a response to the question that vexed many Americans who saw the rise in immigration–roughly 30% between 1900 and 1910–as an issue that threatened American traditions and social stability. Using craft as a means to provide the immigrant population with wage-earning opportunities while instilling in them the Colonial history of America, the Paul Revere Pottery straddled progressive-era idealism and conservative fears that have defined the American experience in the modern era. |  Frances Rocchi (decorator) for Paul Revere Pottery, Bowl, 1909. Glazed earthernware, 3 1/2 x 12 1/4 inches (d). Image courtesy of Rago Arts and Auction Center. Frances Rocchi (decorator) for Paul Revere Pottery, Bowl, 1909. Glazed earthernware, 3 1/2 x 12 1/4 inches (d). Image courtesy of Rago Arts and Auction Center. |

| 7.4 | Sat., Dec. 12, 2020 | Session 4: Educating the Next Generation of Reformers: Charles Binns and the Alfred University Legacy If craft held the promise of reform and recovery for a weary populace, one aspect of its successful implementation that industry could not address was the training in and promotion of the skills necessary to ensure its own survival. Enter Charles F. Binns, “the father of American studio ceramics” the man whose skill and dedication as an educator and ceramist professionalized the craft and ensured it thrived. Binns’ work touched nearly every aspect of Arts and Crafts ceramics too, from Marblehead (with the education of Arthur Baggs) to Grueby (Frederick Walrath, a student, was sent to the pottery to address issues with the glazes), to Robineau, who was among his early students and devotees. This session explores the role of Binns as teacher, chemist, and influencer on the broader field and positions him as a central figure in American ceramic history. |  Walrath Pottery, vase, ca. 1910. Glazed stoneware, 13 1/2 inches. Image courtesy of Rago Arts and Auction Center. |

OCTOBER 2020 series:

6. THE CRAFTSMAN: The Life & Work of Gustav Stickley

| 6.1 | Sat., Oct. 3, 2020 | “There is Properly No History; Only Biography”: The Life and Work of Gustav Stickley In his essay “History,” from 1841, Ralph Waldo Emerson made the bold–and strikingly modern–claim that “All history is subjective. There is properly no history; only biography.” We begin the celebration of Stickley this month with a close look at his biography, examining Stickley’s life and tracing his output from the earliest forms we know of, to the latest pieces he made in his long and storied career. The session will shed new light on aspects of Stickley’s career and demonstrate that the origins of his Arts and Crafts sensibilities began well before he published “New Furniture from the Workshop of Gustave Stickley” in 1900 and discuss–for the first time–a previously unknown company that he founded. |  |

| 6.2 | Sat., Oct. 10, 2020 | “Devoted to the New Domestic Art”: Craftsman Homes and the Birth of Stickley’s Empire If The Craftsman served as the means by which Stickley introduced new audiences to the philosophy behind his furniture, it was his Craftsman houses that made these aspirations concrete: they became a means by which people could realize their aspirations and actively an engage the Arts and Crafts as a lifestyle. From the genesis of this idea in May 1903’s “The Craftsman House,” through the designs of Harvey Ellis later that year, to the formation of “The Craftsman Homebuilder’s Club” in April 1904, this session traces the evolution of Stickley’s Craftsman Houses. In addition to the history of this aspect of Stickley’s career, this session brings you inside the Parker House, an immaculately preserved and privately-owned Stickley home with original woodwork and fireplace system. |  |

| 6.3 | Sat., Oct. 17, 2020 | “The Cultivation of Human Sympathy”: Stickley’s Early Factory and the Ideal Workshop There exists a tension, inherent in any discussions of the Arts and Crafts movement, between the ideals assigned to the movement, and the economic realities that governed production, and hindsight is often too blunt an instrument to be useful. This session explores the early factory of Stickley–from 1898 to 1904–and his productions, not through the false binary of a gauzy idealism vs. insincere capitalist pandering, but looking more deeply at his factory as a mediation between these competing poles. Originally planned as a topic for the Stickley Weekend Symposium, it is a more nuanced look at the current exhibition that explores the degree to which Stickley achieved –as Oscar Lovell Triggs wrote in The Craftsman–“a form of labor which aims to be artistic one the one hand and educative of the other.” It frames Stickley’s factory in relation to Triggs’ ideal workshop, of which “the cultivation of human sympathy–that delicate something that is the source of all high endeavor” was a measure of success. |  |

| 6.4 | Sat., Oct. 31, 2020 | “By Hammer and Hand”: A New History of Stickley’s Metal Shop Perhaps no other aspect of Stickley’s career is in need of revision than his decision to expand the factory into the production of metal wares in late 1902. New evidence has challenged much of the conventional wisdom that surrounds the shop history and sheds new light on the timeline of the work, the workers who made the objects, and the sources that Stickley looked to for design ideas as he developed this aesthetic. What emerges from synthesizing these new sources is a more complete, and complicated, history of the shop that elevates previously unknown workers and companies to replace of the names to which we have grown accustomed. |  |

SEPTEMBER 2020 series:

5. The Creative Spark: Rethinking Decoration in the Arts and Crafts Movement

| 5.1 | Sat., Sept. 12, 2020 | George Ohr: Ceramic history, craft pottery, and the avant-garde in America George Edgar Ohr was a powerful potter; even more than a hundred years after his death he is still in control of the narrative of his life. He was–and remains–”the mad potter of Biloxi,” the “apostle of individuality,” “the greatest art potter on earth,” a sophisticate and rube, the man of a thousand nicknames. This sessions looks at Ohr as all of those things but acknowledges his deep engagement with contemporary and historical ceramics, reevaluates his relationship to craft potters of the period, and sheds new light on his rambling travelogue “Some Facts in the History of a Unique Personality,” which was published in 1901. |  Vase, Earthenware, George E. Ohr, 1900, Gift of Robert A. Ellison Jr., 2017, The Metropolitan Museum of Art |

| 5.2 | Sat., Sept. 19, 2020 | The Anvil Chorus: Facts and Fictions of the Roycroft Metal Shop As unlikely as it seems, the Roycroft Community was amongst the movement’s longest-surviving shops, producing metalwork for nearly four decades. To put this in perspective, that is longer than Robert Riddle Jarvie, Gustav Stickley, and Karl Kipp’s Tookay Shop combined. From the problematic nature of the “early, middle, late” system of marks, to what we know and don’t know about the maker’s marks, this class is a blend of connoisseurship, history, and critical thinking. We will cover the history of the shop from inception through the 1930s, the finishes developed by the shop, and the numbering systems assigned throughout the endeavor’s long duration. |  American Beauty Vase, ca. 1912; Manufactured by Roycroft Shops (United States); USA; copper; H: 56.51 cm (22 1/4 in); Museum purchase from General Acquisitions Endowment; 1984-104-1, Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum |

| 5.3 | Sat., Sept. 26, 2020 | “Tortured by Exaggerated Lines“: The Decorative Impulse and the Arts and Crafts In the opening issue of The Craftsman, Stickley informed readers: “We are no longer tortured by exaggerated lines the reasons for which are past divining. We have not to deal with falsifying veneers, or with disfiguring so-called ornament. We are, first of all, met by plain shapes which not only declare, but emphasize their purpose.” But perhaps he spoke too soon–or only for himself. Despite protestations to the contrary, many in the Arts and Crafts movement reveled in tortured and exaggerated lines, disfiguring ornament, and ornament in many mediums. From the heavily carved furniture of Karl von Rydingsvärd and Charles Rohlfs, to the iron work of Frank Koralewsky, to the painted work of Arthur and Lucia Matthews, the movement was not only the restrained and staid vision that Stickley often promoted in the Craftsman, but included diverse and enthusiastically contradictory set of practitioners who celebrated the decorative impulse. |  Lock, Iron with inlays of gold, silver, bronze, and copper on wood base, Inscriptions: “Fkoralewsky” on iron surface; “FK” inlaid in copper, Dimensions: 50.8 × 50.8 × 20.3 cm (20 × 20 × 8 in.), Frank L. Koralewsky, 1911, American, Art Institute of Chicago |

AUGUST 2020 series:

4. Making Her Mark: Women in the American Arts and Crafts Movement

All too often the history of the Arts and Crafts movement is told from a male perspective that undervalues the contributions and skills of the women who helped define the practice and aesthetics of this period. As individual craft workers, to key players in larger concerns, to the heads of major operations, women were essential to the movement. Making Her Mark: Women in the American Arts and Crafts Movement is a four-part series that explores the female artisans, entrepreneurs, and educators that shaped the movement many so cherish today.

| 4.1 | Sat., Aug. 8, 2020 | Newcomb College: An Art Industry for Southern Women Emerging out of the Reconstruction period’s mentality and fusing that with the emphases on self-improvement and manual training espoused by many in the Arts and Crafts movement, Newcomb College became a locus for artistic achievement that provided women the skills necessary for dignified employment at a time when options were severely limited. In an abrupt inversion of the societal norms, men’s roles at the enterprise were almost entirely as support staff, their contributions limited to the manner in which they could assist with the broader mandate of elevating the work and vision of the craftswomen. This session explores the contributions of Newcomb College, from pottery to metalwork to textiles, not only for the artistic qualities recognized both then and now, but as a model for the advancement of young women that shaped other ventures in the period. |  Newcomb Pottery Building. Washington Avenue Campus, ca. 1905. Newcomb Art School Scrapbook, University Archives, Tulane University. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. Newcomb Pottery Building. Washington Avenue Campus, ca. 1905. Newcomb Art School Scrapbook, University Archives, Tulane University. Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license. |

4.2 | Sat., Aug. 15, 2020 | Tough as Nails: Female Metalworkers of the Arts and Crafts Although the field of metalwork tended to be dominated by males in the period, women played a crucial role in the dissemination of the aesthetic and the rising popularity of hand-crafted metalwork throughout the first decades of the twentieth century. This session focuses primarily on the careers of Jessie Preston and Elizabeth Copeland, using their work and lives as a lens to think more broadly about the contributions of craftswomen in this field. While both were heralded in the time as exceptional designers and skilled craft workers, their paths diverged in the 1910s as Preston shifted her focus to the rehabilitative aspects of handicrafts, eventually traveling to France to work with soldiers wounded in World War I. By unpacking the careers of these two exceptional women, the full range of Arts and Crafts ideals is explored and made concrete. |  American silverware in the Art Institute of Chicago, Elizabeth E. Copeland. Sailko / CC BY https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 American silverware in the Art Institute of Chicago, Elizabeth E. Copeland. Sailko / CC BY https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0 |

| 4.3 | Sat., Aug. 22, 2020 | Industry Leaders: Maria Longworth Nichols, Louise McLaughlin, and Susan Frackleton The history of art pottery in the United States cannot be told without recognizing the tremendous impact that women had on the development of this industry. More than forty years before the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment finally guaranteed their right to vote, women were reshaping the ceramics industry in large operations and as individual ceramists. This session examines three of the most important contributors to the field to think about the women who shaped this field as industry leaders whose work continues to shape the manner in which we understand and appreciate American Art Pottery. |  Susan Stuart (Goodrich) Frackelton, American painter and ceramics artist, Public Domain. |