Making Furniture in a Factory Setting

Retailing for $23.00 in 1901, the Double Manor Hall Seat (no. 155) was the costliest of benches offered in the New Furniture catalog. Wrapped in Spanish leather and over two feet long, it required more wood, more leather, and more time to make than similar but less expensive designs like the single Hall Seat (no. 151) with a wooden top, which retailed for $13.00.

Although a bench–by its nature–is a humble piece of furniture, the factory system that Stickley used to create his furniture meant it went through the hands of numerous workers, many with specialized skills, in its journey from inception to inclusion in the catalog.

THE DESIGN PROCESS

The design process in a factory is by definition collaborative. Regardless of what a designer envisions, there are practical considerations such as cost of materials, the preferences (both aesthetic and economic) of the stakeholders, the manner in which design impacts workflow, and the expense of labor that all shape the final product.

One of Stickley's earliest designers, René James Wales, has been largely lost to history and unrecognized in previous scholarship. Documented in Stickley's shop as early as 1899, he appears to have moved to Syracuse sometime in the prior year and appeared in the City Directory for 1899 as a "designer." By 1901 the directory noted he was removed to Oneida, probably to rejoin his family as his father DeFlorence Wales lived there.

The 1905 New York State Census recorded Wales as married, living in Oneida, and employed as the foreman of a casket factory. Although he continued to maintain a residence in Oneida, by 1910 he also appeared in Springfield, Massachusetts as the foreman of a "cas. shop," presumably the American Casket Company.

LABOR AND THE LABORER

The laborer is the connective tissue that binds together the different processes of furniture making. From the initial gathering of the material from the yard to loading finished pieces for delivery, the laborer is the unseen link between each step. Although the lowest paid of all employees these men performed a crucial role in production.

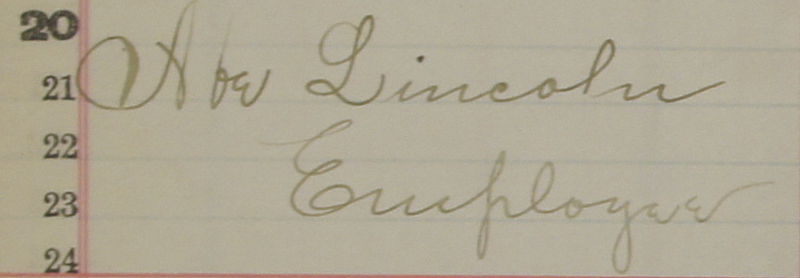

Abraham Lincoln (1834-1903)

Had Stickley simply given Abraham Lincoln whatever he purchased for $1.00 in December 1898, there would have been no need to record the transaction in the General Ledger and Lincoln's employment for Stickley would have gone unnoticed. Few traces of his presence remain, but the 1900 Federal Census paints a picture of a difficult life. His birth was recorded as January 1834, in Maryland; his wife Mary's was listed as 1829 in North Carolina. Mary had borne eleven children by this time, though only one survived to 1900. Lincoln is the first person of color documented working in Stickley's factory.

Significantly, no trace of Lincoln or his wife have been located prior to the 1870 Federal Census. His name, race, illiteracy, and birth within a slave state strongly suggests he was a former slave. The date of their marriage–just one year after the end of the Civil War–seems only to strengthen this possibility. Like many former slaves, Lincoln may not have known the precise year of his birth (nor would it have been documented in the public record) and this may explain some of the various dates and places associated with his birth. In 1870, census takers recorded him as 45 years old and born in Pennsylvania. In 1880, he was presumed to have been 60 years and born in New York, though in the 1892 New York State Census he was listed as 75 years old. He died on February 20, 1903 in Syracuse and is buried at Oakwood Cemetery.

SHAPING: MACHINISTS AND TURNERS

Stickley's factory was highly mechanized and most of the work was done with machines assisting workers in their tasks. Machinists were the first line of labor in the shaping process and their job was to take the lumber that laborers brought in and begin to work it into serviceable pieces that could be handed off to more skilled craftsmen.

When materials came in from the yard, they would go through a process of initial shaping by one of the numerous machinists, like Henry C. Voight, employed in Stickley's factory. Some pieces, in particular the legs, required more specialized workmen to finish them prior to assembly. These would be brought to employees like Albin H. Walters, a wood turner employed by Stickley at the time the New Furniture catalog was published.

Walters, like many of Stickley's employees, was an immigrant. Born in Germany in April 1850, he came to the United States in 1885 and by 1892 was living in Binghamton, NY and working as a wood turner. He continued to work in the furniture industry throughout the 1910s, though he adapated by working as a veneerer rather than a turner. He died on December 10, 1924.

SPECIALISTS: CHAIRMAKERS

In many ways, the transfer of the various components to the chairmakers represented the first step in the assembly of the final piece. Until now, all of the labor was directed towards the gathering of materials and making of the required elements. The chairmakers (and their counterparts the cabinet makers) were tasked with bringing the final form to fruition.

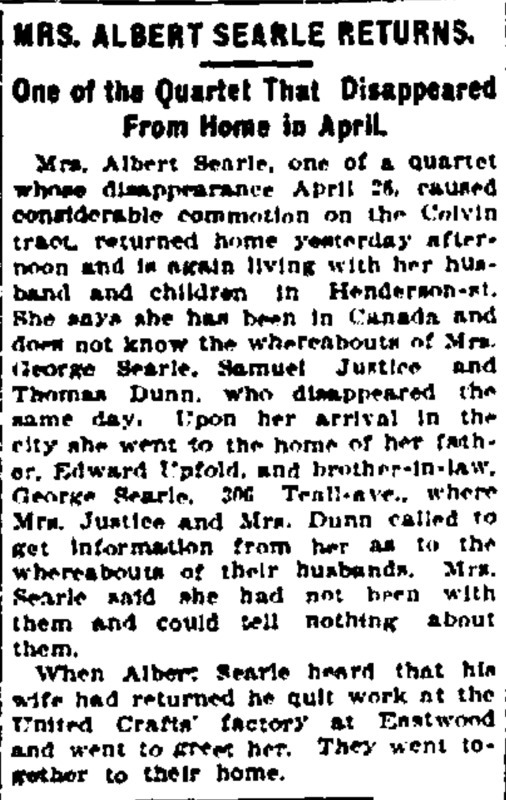

Chairmaker Albert E. Searle was working for Stickley as early as 1896. Born in England, in 1870, Searle emigrated to the United States in 1892 and lived in Syracuse by 1893. The Searle and Upfold families were apparently close-knit: both had members working in Stickley's factories and Albert and his brother George both married Upfold sisters.

Unfortunately, those ties were not enough to make for easy marriages as the Syracuse Newspapers reported extensively on the attempted elopement of both Mrs. Searles, the subsequent warrant issued against them by Albert for larceny, and the nightly demonstrations outside their home that ensued. Describing a crowd of nearly 500 that gathered the night before, The Syracuse Journal noted: "their anger is directed principally at Mrs. Searle the neighbors say they have no further use for the husband since he has taken the woman back. ...The crowd begged her to come out that they might give her a coat of tar and feathers."

FINISHING AND TRIMMING

After the seat was completed, the piece would have been stained and finished. As W. Michael McCracken has noted, the process of fuming oak began in earnest in late 1901, as the factory's January 1902 inventory lists only eighteen pieces that have been treated this way, all of which are samples.

Edward Upfold was among the ten or so furniture finishers documented in Stickley's factory at the time of the New Furniture production. Born in England, in March 1871, he is recorded with Stickley as early as date and at least through 1911. Upfold must have been particularly good at his job: he was the only employee that Stickley brought from Syracuse to work on Craftsman Farms. Upfold spent three weeks in New Jersey and is likely responsible for the staining and finishing of the woodwork throughout the Log House.

Families were an important part of Stickley's workforce in 1900, with multiple generations from the same family and multiple members of the same generation often working together in the factory. Wood turner Albin Walters' son, also named Albin, was employed as a wood carver. Brothers Henry and Jesse Joseph Eisinger both worked as finishers. Daniel Humberstone, a finisher who rose to foreman, brought his younger brother George on to the workforce; Edward Upfold's sisters were married to George and Albert Searle.

SEATING OPTIONS: UPHOLSTERY

Although assembly is basically complete, Hall Seat (no. 155) is essentially indistinguishable from its less-expensive counterpart, the wooden topped Hall Seat (no. 154). Some seating had a wooden seat, though most of the forms Stickley produced required either rush seating, fabric, or leather upholstery.

Thomas Herbert Spratt (1879-1965) worked for most of his life as an upholsterer and is documented with Stickley by 1899, at precisely the time when the ‘new furniture’ was being developed. Unlike Stickley’s later catalogs, New Furniture from the Workshop of Gustave Stickley tended to downplay the upholstering options, mentioning only when a form featured Spanish leather. The 1901 factory inventory and later retail plates are much more specific and demonstrate the wide range of choices available to consumers at this time: leather, tapestry, denim, and a number of different fabrics were available as options.

ASSEMBLING THE CATALOG

Once the final piece was assembled and approved, it needed to be photographed for inclusion in the catalog. The 1901 factory inventory suggests that this part of the operation was done in house, as both a "dark room" and "photo stand" are recorded as part of the rubbing room fixtures. The placement of the equipment here meant that it could be photographed in as close to a pristine state as possible–since it did not have to be moved anywhere–and avoided the extra costs of the labor associated with moving it from floor to floor.

Lester Standen worked as a photographer for Stickley in at least 1899 and would have been responsible for photographing the furniture and developing the prints that would be used in the catalogs. The very act of publishing a catalog was a departure for Stickley, as no catalogs have been located from his previous endeavors. Rather than contracting this process, Stickley used an in-house team that included the artist Frank J. Russell and probably Frederick Meeker, an English-born printer.