An online course presented by The Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms.

With Instructor, Dr. Jonathan Clancy, Director of Collections and Preservation.

23 Sessions in 3 Parts | $25/session | Location: Zoom Online Classroom

Part 1: 6 Sessions; Recorded Jan 23 – Feb. 27, 2021

Part 2: 9 Sessions; Recorded March 27 – May 22, 2021

Part 3: 8 Sessions; Recorded July 10 – August 28, 2021

Design & History: The Past is Always Present

COURSE OVERVIEW

Writing in 1841, Ralph Waldo Emerson recorded one of the immutable laws of the creative process: “the new in art is always formed out of the old.” So while the Arts and Crafts movement appeared to be a new direction in design, it was indebted to the precedents of our collective past, the shared history of design that was understood amongst its manufacturers, designers, and fiercest advocates. This series seeks to recapture those precedents, not to dilute the importance of the movement, but to better understand it, to wrap it properly in the context of the histories from which it emerged so that its contributions – and the meanings which these objects held to contemporaries – become clearer. Explored in this manner, design is not only practical, but metaphorical, lyrical, and poetic. It speaks to us in the hushed and reverent tones of our shared experiences if we can learn to listen to and discern those muted murmurs.

2021 – 1.

Design & History: The Past is Always Present — PART 1

| 21.1.01 | Sat., Jan. 23, 2021 | Reimagining the Gothic: Roots of a Revolution There is no period more appropriate to begin the historical precedents of the Arts and Crafts movement than the Gothic, a new expression of religious sentiment that flourished in Europe during the 12th to 15th centuries. It provided – for the Pre-Raphaelites, English reformers, and American exponents – a perfect metaphor for their renewed commitment to craft and came to stand as the last moment of pure sincerity in a world that became increasingly illusionistic and insincere since the Renaissance. From the rise of the movement’s broader acceptance in the 12th century to its height in the 14th century, we explore the meaning of the Gothic, review the forms and terms you’re likely to encounter, and discuss its impact in the late 19th century. |  Rose Valley, Library Table, 1904. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Rose Valley, Library Table, 1904. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 21.1.02 | Sat., Jan. 30, 2021 | East Meets West: The Birth of Global Design Western fascination with the Asian aesthetic exploded in the 17th century, as the formation of the Dutch East India Company in 1602 expanded commercial activity and brought sustained contact with Asian objects to increasing numbers of consumers. Throughout the 17th century, this radically changed the course of design history as the Chinese taste forced European manufacturers to adapt their own wares to these latest styles. The chinoiserie, japonisme, and orientalism that flourished from the 17th to 19th centuries (and which many in the Arts and Crafts movement were indebted to) began here. The dialog between the East and West was amongst the earliest manifestations of globalism that continues to shape our aesthetic in the modern era. |  Chelsea Keramic Art Works, Vase, ca 1885-89. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Chelsea Keramic Art Works, Vase, ca 1885-89. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

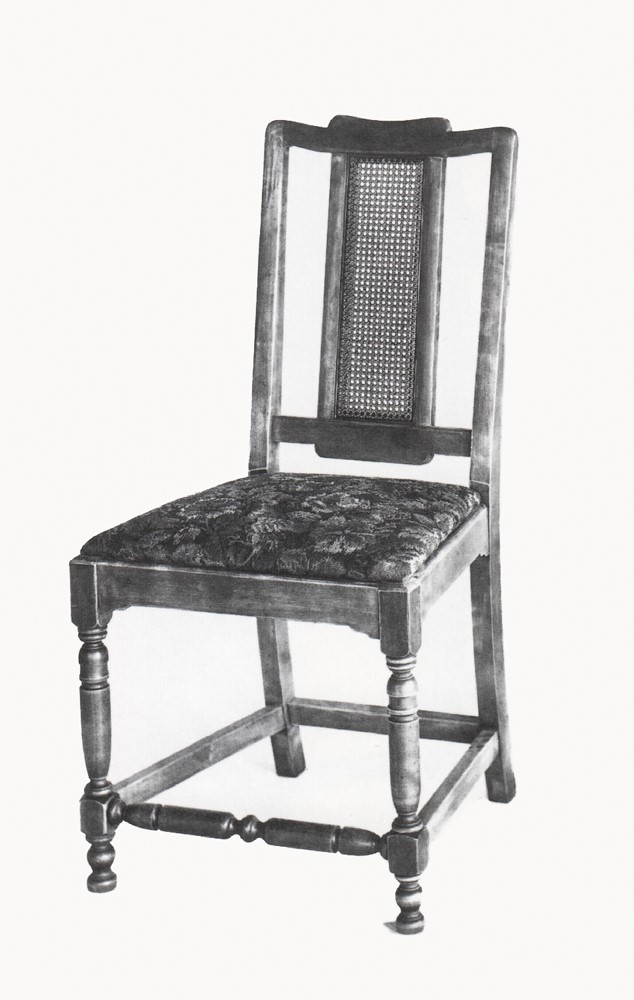

| 21.1.03 | Sat., Feb. 6, 2021 | Drama, Design, and Deposed Rulers: William and Mary as Tastemakers From the late 17th century to the 18th century, Europe was spellbound by the rise of William and Mary, the son-in-law and daughter of James III who deposed the English King and ruled as joint sovereigns until her death from smallpox at age 32. Cosmopolitan and wealthy, the couple’s reign marked a period of aesthetic innovation that saw the rise of Japanning (a technique by European furniture makers to imitate Asian lacquerware) and increased dispersion of skills between continental craftsmen and their English counterparts. Following William’s death in 1702, his sister-in-law, Queen Anne ascended to power and continued the transformation of the Western aesthetic, overseeing a period that became more graceful and less rectilinear. These styles were ones that Stickley returned to early (and later) in his career, hoping to capitalize on the rising tide of the Colonial Revival aesthetic and the associations of honesty, craftsmanship, and good design with which Americans imbued these movements. |  Gustav Stickley, The Craftsman, Side Chair, ca. 1915-17. Gustav Stickley, The Craftsman, Side Chair, ca. 1915-17. |

| 21.1.04 | Sat., Feb. 13, 2021 | Somewhat Naughty, Frequently Haughty, and Occasionally Bawdy: The Rise of the Rococo If you listen closely, you might here the indignant question: “What does the Rococo have to do with Stickley, in particular, or the Arts and Crafts, in general?” The answer is really twofold. First, Stickley’s revival furniture of the 1890s and later 1910s relied heavily upon the “Chippendale,” the English manifestation of the movement named for the celebrated cabinet-maker. Second, as Emerson reminded us in “Art,” “the very avoidance betrays the usage he avoids.” For Stickley–like many in the Arts and Crafts–the Rococo served as inspiration and foil, it was powerful, almost talismanic; it simply could not be avoided. Beginning with career of Watteau (ca. 1710), the Rococo was everything the Baroque could never be: light, playful, sin-filled, and curvaceous. It was an era of increased trade with colonies in the Americas, which gave rise to the increasing use of mahogany and other exotic materials. It was so popular in fact, that after going out of style by 1800, it was revived by the 1840s, and formed the foundation for much of the Colonial Revival aesthetic. |  Gustave Stckley Co., Arm Chair (no. 263-A), ca. 1898-1903 Gustave Stckley Co., Arm Chair (no. 263-A), ca. 1898-1903 |

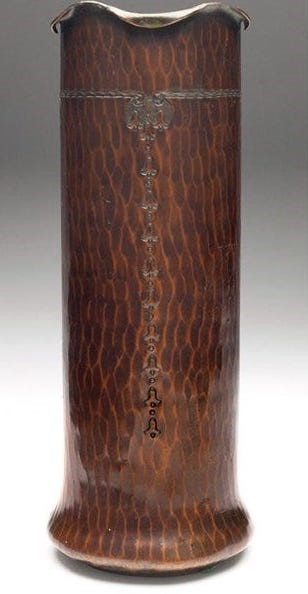

| 21.1.05 | Sat., Feb. 20, 2021 | The Apotheosis of Neoclassicism (or How the West got Serious Again) Since the rediscovery of Pompei and Herculaneum in the early 18th century, Europe was enthralled with classicism, a sensation that finally became full-blown in the late 18th century. From the paintings of Jacques-Louis David to the ceramics of Wedgwood to the furniture of Sheraton, there was a flourishing neoclassicism that swept across Europe and became the dominant style at the beginning of the 18th century. Eschewing the frivolity and playful fun of Rococo excess, this was a serious style whose gravitas was conveyed by restrained lines, gentle curves, and the return of symmetry. Gone were the nude maidens of Boucher frolicking in the waves, replaced instead by the imagined past of classical times–urns, garlands, myths, and bellflowers, rigid and unwavering in their precision, became the preferred decorative scheme. |  Roycroft Shops, Vase (no. 213), ca. 1918. Treadway Toomey Auctions. Roycroft Shops, Vase (no. 213), ca. 1918. Treadway Toomey Auctions. |

| 21.1.06 | Sat., Feb. 27, 2021 | You Are What You Eat: Food, Globalism, and the Transformation of Design It is difficult to fully appreciate that the simple pleasures we take for granted today–coffee, tea, and chocolate–were extravagant novelties that transformed the world of material culture (and culture in general) by their introduction. Simply put: new foods called for new forms. The consumption of these goods engendered new rituals that changed how we interacted, what we needed to interact, and the very spaces in which we interacted. Globalism, and in particular the new commodities it brought into the western palate, meant the introduction of forms–from spice mills to sugar boxes to tea pots and tea tables–that were previously unimaginable as a part of daily life. This session explores the transformation of design–not as an aesthetic phenomenon–as a need-based reaction to a world struggling with how to make sense of globalism and to domesticate its benefits into the rituals of consumption. |  Charles Rohlfs, The Rohlfing Dish, 1904. Toomey & Co. Auctioneers. Charles Rohlfs, The Rohlfing Dish, 1904. Toomey & Co. Auctioneers. |

2021 – 2.

Design & History: The Past is Always Present — Part 2

Writing in 1841, Ralph Waldo Emerson recorded one of the immutable laws of the creative process: “the new in art is always formed out of the old.” So while the Arts and Crafts movement appeared to be a new direction in design, it was indebted to the precedents of our collective past, the shared history of design that was understood amongst its manufacturers, designers, and fiercest advocates. This series seeks to recapture those precedents, not to dilute the importance of the movement, but to better understand it, to wrap it properly in the context of the histories from which it emerged so that its contributions – and the meanings which these objects held to contemporaries – become clearer. Explored in this manner, design is not only practical, but metaphorical, lyrical, and poetic. It speaks to us in the hushed and reverent tones of our shared experiences if we can learn to listen to and discern those muted murmurs.

| 21.2.01 | Sat., March 27, 2021 | A More Muscular Classicism: The Western World in the Early 19th Century At the end of the 18th century, when Europe was consumed by a delicate neoclassicism that presented an austere sense of order in contrast to the sinewy, riotous curves of the Rococo, new ideas were afoot. Gradually, the delicacy of the late-eighteenth century gave way to a classicism that was bold, muscular, and imposing. Known by different names throughout Europe and the United States, the Empire or Biedermeier style took the vocabulary–the building blocks–of classicism and reconfigured them into a distinctly different approach to design that shaped design over the following decades. |  Fall Front Desk (Vienna), ca. 1810. Various woods and gilt bronze. Art Institute of Chicago. |

| 21.2.02 | Sat., April 3, 2021 | Egypt and Egyptomania Following Napoleon’s conquest of Egypt at the turn of the nineteenth century, Western decorative arts experienced their first profound wave of Egypto-mania, relishing in the exoticism of a distant past and mystical land. Pyramids, sphinxes, and papyrus leaves began to appear on designs on furniture, ceramics, and architecture across Europe and the United States, fueled by scientific exploration and the publication of findings. By the 1820s, scholars had begun to decipher the Rosetta Stone, which made a past that had been previously lost to time suddenly decipherable. This session explores the aesthetics of Egyptian art and architecture that Europeans encountered, and examines how these impacted design and decoration in the 19th century, from Wedgwood to the Herter Brothers. |  Pottier and Stymus (attr.), table, 1870-75. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Pottier and Stymus (attr.), table, 1870-75. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 21.2.03 | Sat., April 10, 2021 | Greek Arts and The Greek Revival While the discoveries of Pompeii and Herculaneum captured the imagination of 18th century designers, a quiet revolution was brewing, one that would look back further in antiquity to prize the quiet grandeur of all things Greek to the excessive exuberance of Roman design. In this session, we move again in two directions: back to the Greeks to understand the essential aesthetics that shaped their particular contributions to Western art history, and into the 19th century where a revival of these ideas spurred advancements in architecture and design in Europe and the Americas. By looking closely at Greek art and architecture, we’ll see another side of the many classicisms that were available to 19th century designers and witness how these masterpieces of antiquity were updated for modern life. |  Duncan Phyfe, Couch, ca. 1837. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Duncan Phyfe, Couch, ca. 1837. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

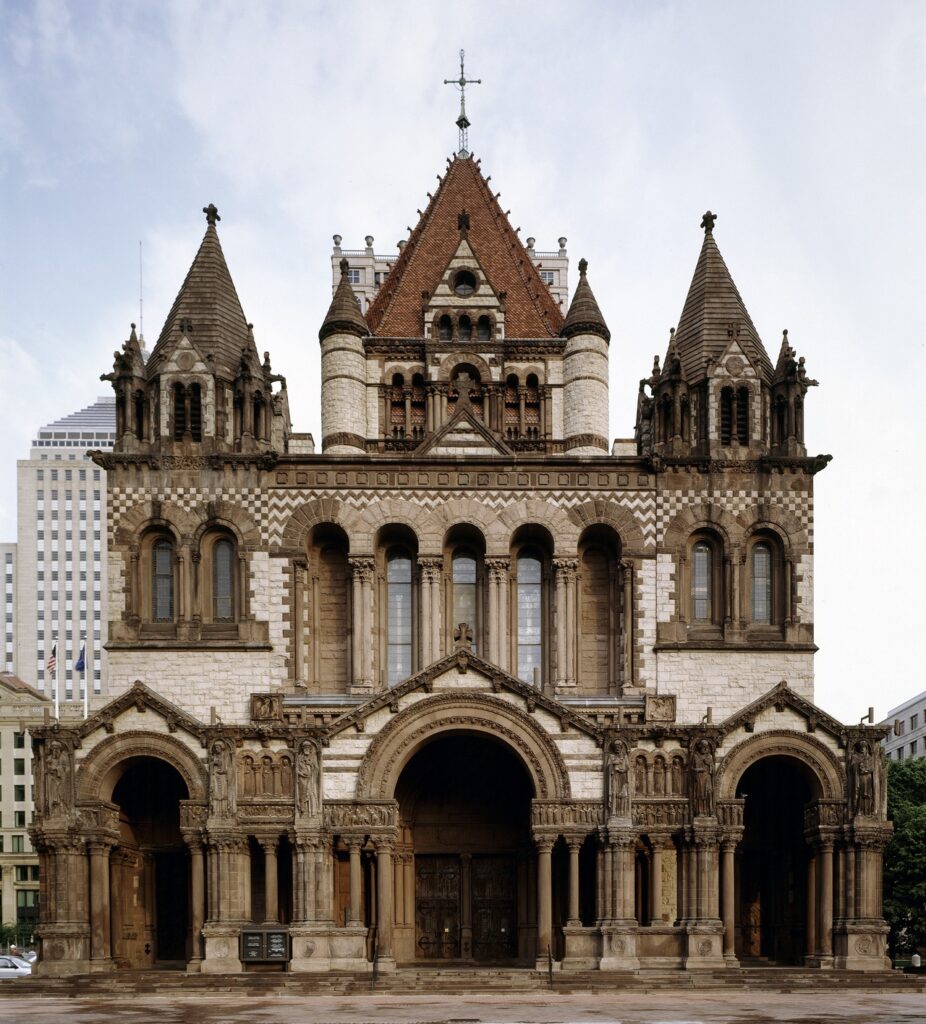

| 21.2.04 | Sat., April 17, 2021 | Romanesque, the Romanesque Revival and Henry Hobson Richardson Eschewing the fancy marbles and high-style of the Greek Revival and other classicisms, Henry Hobson Richardson created an alternate type of historicism in the late 19th century that preserved the grand scale of those other styles but spoke to the rustic handwork that was increasingly prevalent. Known today as Richardson Romanesque–and perfectly illustrated by his masterwork Trinity Church in Boston–Richardson drew upon European architecture of the pre-Gothic period to create his bold vision. This session will explore not only the major works of this style in depth, but look too at the origins of this movement–the Romanesque period–to better understand the aesthetic Richardson helped shape by looking at what he preserved and ignored from our collective past. |  Henry Hobson Richardson, Trinity Church, 1872-77. Boston. Henry Hobson Richardson, Trinity Church, 1872-77. Boston. |

| 21.2.05 | Sat., April 24, 2021 | Pugin and the 1851 Crystal Palace Exposition While the 19th century was marked by an exuberance for technological advancements, there was still more than enough anxiety about the changing world to go around. As the first World’s Fair celebrated humanity’s progress, it was marked too by the desire to return to the simplicity of the middle ages most forcibly stated by Augustus Welby Northmore Pugin’s Medieval court exhibited in the Crystal Palace. This session explores the critique of modernity that flourished in the wake of this exhibition covering such well-known names as John Ruskin and William Morris, but giving proper credit to Pugin whose 1836 publication of Contrasts in 1836 would set the stage for the medievalizing fantasies of subsequent design reformers and critics of modernity. |  View of the Crystal Palace, ca. 1854. View of the Crystal Palace, ca. 1854. |

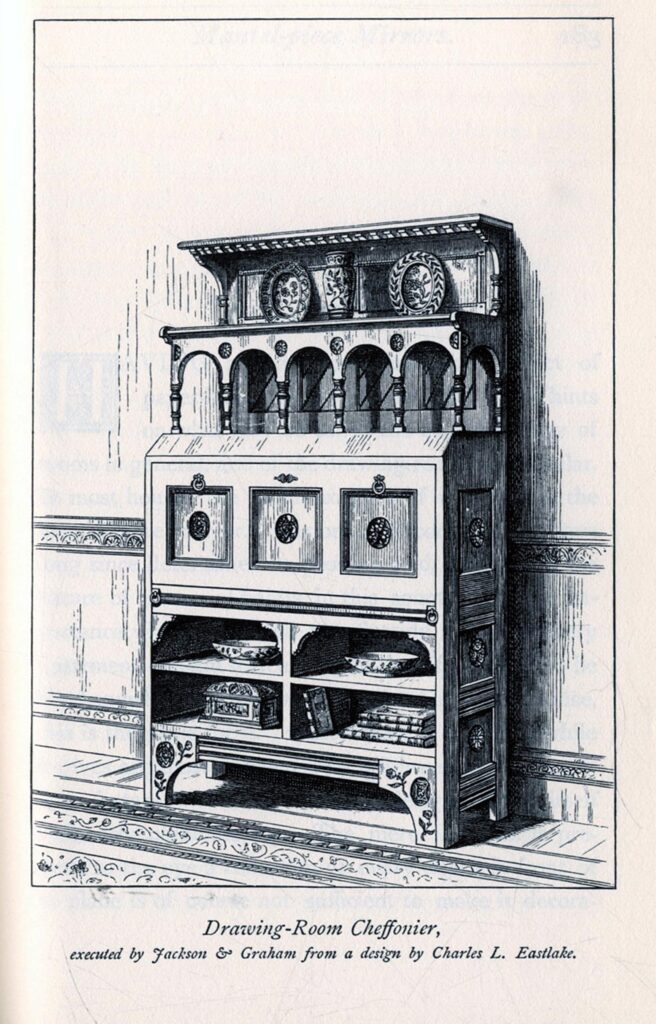

| 21.2.06 | Sat., May 1, 2021 | Charles Eastlake and Design Reform in the Late 19th Century It is difficult to underestimate the impact of Charles Eastlake’s Hints on Household Taste in Furniture, Upholstery and Other Details published in England in 1868, then in the United Sates in 1872. With a focus on the middle class as opposed to the monied elite, Eastlake’s influence was immediately felt through attractive furniture that he claimed could be mass-produced “as cheap as that [furniture] which is ugly.” In the United States, where his book underwent six printings, his ideas impacted furniture design, architecture, and came to epitomize what we think of as “Victorian” today. And yet, a close reading of Eastlake reveals not the polar opposite of the Arts and Crafts movements as we sometimes think, but surprising through lines and connections. |  Drawing Room Chiffonier, designed by C. L. Eastlake. Drawing Room Chiffonier, designed by C. L. Eastlake. |

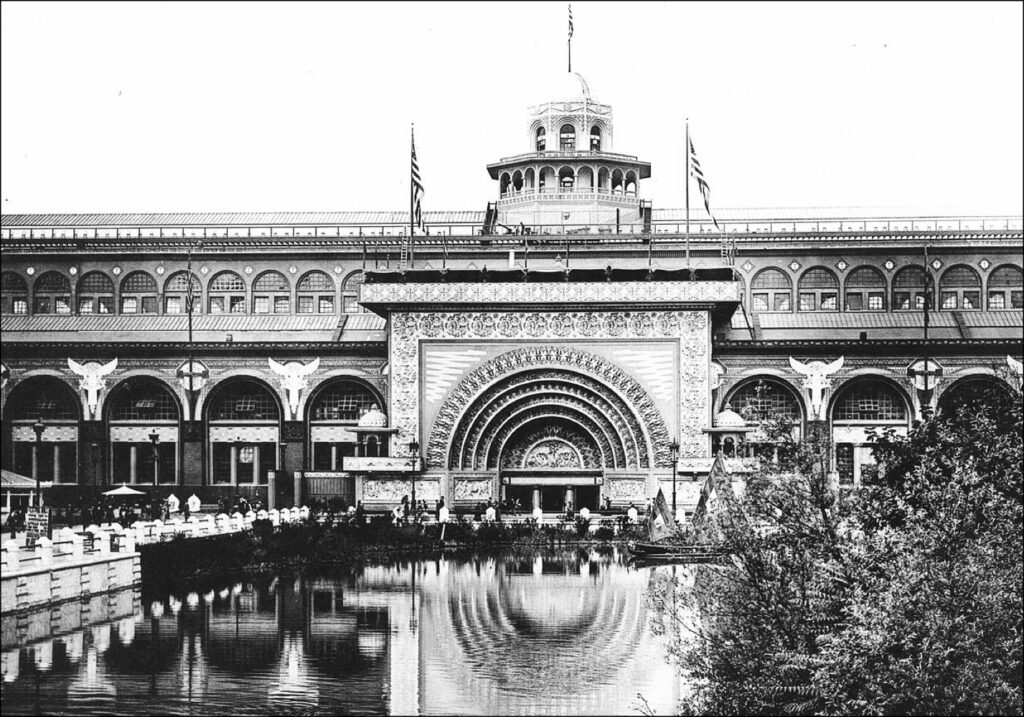

| 21.2.07 | Sat., May 8, 2021 | Classical Splendor in the Modern World: The White City and the Columbian Exposition In the same decade we witnessed the rise of the Arts and Crafts, the Prairie School, Colonial Revival, and Art Nouveau movements, Chicago’s Columbian Exposition of 1893 saw “the White City” emerge from the shores of Lake Michigan to transform American civic design and help spur the City Beautiful movement. If the late 19th century saw an increase in the speed with which change occurred and styles changed, Classicism provided a sense of stability and permanence. Bringing together luminaries like Frederick Law Olmsted, Lorado Taft, and Daniel Burnham the Exposition’s aesthetic–with the notable exception of Louis Sullivan’s Transportation building–relied upon the precedents taught at the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris in the late 19th century. |  Louis Sullivan, The Transportation Building for the Columbian Exposition, 1893. Louis Sullivan, The Transportation Building for the Columbian Exposition, 1893. |

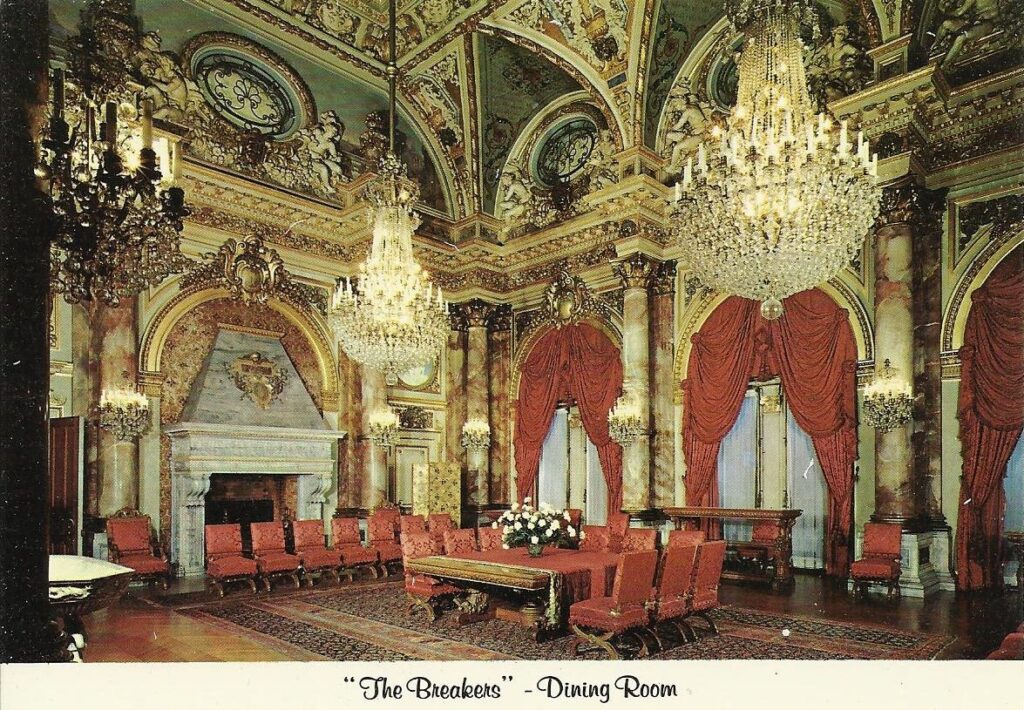

| 21.2.08 | Sat., May 15, 2021 | American Excess: Wealth and Taste in the Late 19th Century At the end of the 19th century, a few citizens of the United States saw a rise in wealth that had previously been the exclusive purview of the nobility. If it was the peculiar circumstances of the American experiment that gave rise to their wealth, it is clear–in hindsight–that their notions of taste were rooted in old world ideas of class, culture, and wealth. This session examines the homes and collections of Isabella Stewart Gardner, Andrew Carnegie, the Vanderbilts, and others to explore how their aesthetics developed and how they continue to impact our understanding of art and architecture today. |  Richard Morris Hunt, Dining Room of the Breakers, 1893. Richard Morris Hunt, Dining Room of the Breakers, 1893. |

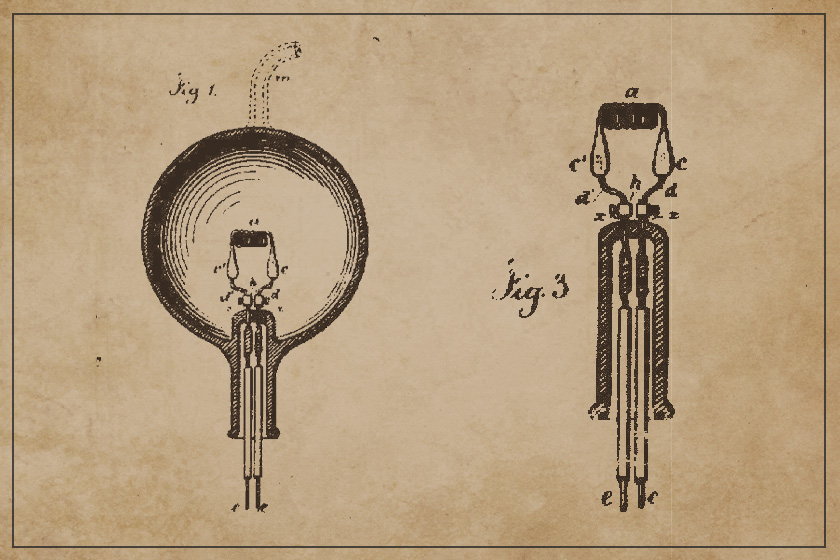

| 21.2.09 | Sat., May 22, 2021 | Technology and the Transformation of the Home In the same way we witnessed how new foods transformed culture in the last series, technology transformed the social structure of the home throughout the 19th century. Advances in lighting, heating, mechanical inventions, and refrigeration throughout this period changed the way we ate, socialized, and used the home. Rather than something fixed, culture–it turns out–is a curious arrangement of pre-existing conditions that is continuously reshaped by the manner in which we assimilate new ideas, new people, and new inventions. It is a reminder too that there is no “American” culture, but rather a series of cultures that simultaneously exist broadly, locally, and always in a constant state of flux. |  Thomas Edison, drawings for an electric lamp, 1880. Thomas Edison, drawings for an electric lamp, 1880. |

2021 – 3.

Design & History: The Past is Always Present — Part 3

As author L. P. Hartley cogently noted in his novel The Go-Between: “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there.” In this final part of the Design & History series we visit those foreign countries, diving deeply into the modern era, examining the pasts that continue to shape our world, and exploring the legacy of, and reaction to, the Arts and Crafts Movement. Starting with Peter Behrens and the birth of industrial modernism, we move through the major movements and figures of the first half of the twentieth century–The Bauhaus, Le Corbusier, Art Deco, and Mid-Century Modernism–before ending at Black Mountain College and the avant-garde.

| 21.3.01 | Sat., July 10, 2021 | Peter Behrens and the Birth of Modern Design As we move into the 20th century, my argument for the first session is quite simple: Peter Behrens was a brilliant designer who should be more of a household name. Competent in a number of different styles from Art Nouveau to Industrial design to Classicism and Expressionism, his work as a designer, architect, and teacher / mentor heralds the birth of modernism as a style. Without the pioneering work of Behrens, there is no International Style, no Dieter Rams of Braun, no Mies or Corbusier or Gropius as we know them, since they all worked as assistants in his office. From his AEG Turbine Hall (1909, Berlin) to industrial clock designs, to his Expressionist masterpiece the Technical Administration building for Hoescht, Behrens proved himself able to change with the demands of the times and the mandate he was given, and ranks amongst the most important designers of the twentieth century. |  Peter Behrens, AEG Turbine Factory, 1909. Berlin. |

| 21.3.02 | Sat., July 17, 2021 | Cubism: The Rise of Geometric Modernism In the first decades of the twentieth century, certain unrelated strains of modernism sprang forth that embraced a fractured, geometric approach to composition best exemplified by the analytical Cubism of Braque or Picasso. And yet, as the Wiener Werkstätte reminds us, these movements predated the very invention of Cubism and certainly its wider distribution. This session explores these trends, looking at varied movements from the Wiener Werkstätte to De Stijl, to Soviet Constructivism and Suprematism, and considers the impulses that were common to that approach, inklings of which were evident in Cezanne’s work by the 1890s. |  Gerrit Rietveld, Red Blue Chair, ca. 1918-23. Museum of Modern Art. Gerrit Rietveld, Red Blue Chair, ca. 1918-23. Museum of Modern Art. |

| 21.3.03 | Sat., July 24, 2021 | Mysticism, Modernism, and Often Misunderstood: The Bauhaus Often thought of as a pinnacle of European modern design, this session explores the Bauhaus from its roots in Henry Van de Velde’s Weimar School for the Applied Arts to its growth under Walter Gropius to what essentially became an architectural laboratory under Ludwig Mies van der Rohe before it was closed in 1933 by mounting pressure from the Nazis. Often overlooked in the Bauhaus history is the persistent influence of Expressionism, mysticism, and the role that handicraft played in the development of the school’s aesthetics. Johannes Itten, a neo-Zoroatrianism, vegetarian, painter, and mystic developed the Basic course of study at the Bauhaus and forms an important counterpoint to the international style that continues to dominate our impression of the movement. Hand weaving, timber structures, pottery making, and embrace of exoticism were essential factors in the development of the Bauhaus. |  Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer, Sommerfeld House, 1920-22. Berlin Walter Gropius and Adolf Meyer, Sommerfeld House, 1920-22. Berlin |

| 21.3.04 | Sat., July 31, 2021 | The International Style Amongst the most recognizable styles of modern architecture and design, the International Style also established the canon of luminaries we continue to revere: Le Corbusier, Mies Van Der Rohe, Marcel Breuer, and Alvar Aalto. Practitioners favored modern materials, balance (as opposed to symmetry), and emphasized the volume of space rather than the mass of the façade. Generally devoid of ornament, part of the appeal of the movement, and indeed its supremacy from about 1930 to the 1980s, was that it was reproduceable ad nauseum anywhere. The unfortunate legacy of the International Style is a staggering amount of non-descript glass and steel buildings all over the world that often distracts from the aesthetic achievements of the movement’s best work. In this session, we will recapture that history, look at what makes for great (and, by contrast, really poor) International Style design, and see the manner in which subtle manipulations of proportion and materials created these iconic structures. |  Le Corbuiser, Pierre Jeanneret, and Charlotte Perrirand, Armchair with tilting back, 1928. Museum of Modern Art. Le Corbuiser, Pierre Jeanneret, and Charlotte Perrirand, Armchair with tilting back, 1928. Museum of Modern Art. |

| 21.3.05 | Sat., Aug. 7, 2021 | Can We Make it Jazzier? Art Deco and the Return of Decoration If the International Style was clean and elegant, it was also cerebral and markedly un-fun. Enter: Art Deco, and with that the realization that decoration, historicism, and visual play were satisfying, uplifting, symbolic, and desirable. From Radio City Music Hall to the Chrysler Building to the SS Normandie, high-style Art Deco’s embrace of luxury materials, contrast, pattern, and decoration formed a welcome relief to the somber elegance of the International Style. This session looks at the return of decoration and the movement’s best designs and designers, including Emile-Jaques Ruhlman, Donald Deskey, Viktor Schreckengost, and Ruth Reeves. |  Donald Deskey, Cigarette Box, 1928. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 21.3.06 | Sat., Aug. 14, 2021 | Craft Workshops in an Era of Mass-Production From George Nakashima to Wharton Esherick, from Gertrude and Otto Natzler to Leza and William McVey, the practice of craft and the notion of the individual studio continued to hold sway even as the acceleration of mass production drove designers and producers farther apart. In this hour, we explore the persistence of the artist producer in the modern economy, highlighting works from the artists mentioned above, but looking too at artists like Harvey Littleton, a revolutionary who resisted modern production methods by taking an art that had been confined to larger practices–glass making–and creating a studio practice that rescued craft from industry. |  Wharton Esherick, Desk, 1970. Courtesy of Rago Arts and Auction Center. |

| 21.3.07 | Sat., Aug. 21, 2021 | Design at Mid-Century: Softer Modernisms Moderne, streamlined, biomorphic, mid-century, these terms denote a school of thinking that arose to fill the gap between the austerity of the International Style and the excessive decorative impulses of Art Deco. Exemplified by figures such as Russell Wright, Eva Zeisel, Charles and Ray Eames, and Isamu Noguchi, these designers sought a middle path and chose to preserve the clean lines of modernism while softening its hardest edges. Their efforts and their collaboration with industry put “good design” within the reach of the masses and helped shape the material culture of that period and even into today. |  Eva Zeisel, Town and Country Salt and Pepper Shakers, ca. 1945. Museum of Modern Art. Eva Zeisel, Town and Country Salt and Pepper Shakers, ca. 1945. Museum of Modern Art. |

| 21.3.08 | Sat., Aug. 28, 2021 | The Black Mountain Legacy: Bauhaus and Beyond With the final closing of the Bauhaus in Berlin in 1933 and the rise of Nazism in Germany, artists and designers–if they were able to–fled. Black Mountain College, in western North Carolina, was the unexpected beneficiary of Germany’s deteriorating political climate as nearly a dozen artists associated with the Bauhaus (including Walter Gropius, Anni and Joseph Albers, and Lyonel Feininger) came to work at the school. Although short-lived–lasting just 24 years from 1933-57, Black Mountain’s impact on American and Art and Design is difficult to overstate: Peter Voulkos, John Cage, Merce Cunningham, Willem de Kooning, Jacob Lawrence, and Robert Motherwell all spent time there. So too did Buckminster Fuller, Albert Einstein, and Ruth Asawa. This session explores this amazing moment, the overlap of art / design / dance / craft / engineering and the impact it continues to have on our world. |  Peter Voulkos, untitled, 1957. Courtesy of Cowan’s Auctions. |

Dr. Jonathan Clancy is the Director of Collections and Preservation at the Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms. An author, educator, and curator Clancy received his doctorate in art history in 2008 from the Graduate Center. Formerly Director of the MA in American Fine and Decorative Arts program at Sotheby’s, he left in 2017 to form an advisory group. As an independent consultant, he has worked with private clients and institutions on collection management, exhibition planning, label writing and research, and valuation.

Craftsman Farms, the former home of noted designer Gustav Stickley, is owned by the Township of Parsippany-Troy Hills and is operated by The Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms, Inc., (“SMCF”) (formerly known as The Craftsman Farms Foundation, Inc.). SMCF is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization incorporated in the State of New Jersey. Restoration of the National Historic Landmark, Craftsman Farms, is made possible, in part, by a Save America’s Treasures Grant administered by the National Parks Service, Department of the Interior, and by support from the Morris County Historic Preservation Trust, The New Jersey Historic Trust, and individual donors. SMCF received an operating support grant from the New Jersey Historical Commission, a division of the Department of State and a grant from the New Jersey Arts & Culture Recovery Fund of the Princeton Area Community Foundation. Educational programs are funded, in part, by grants from the Arts & Crafts Research Fund.