COURSE DESCRIPTION:

The years between 1890 and 1905 saw a revolution in European decorative arts, an almost unanimous agreement that the shackles of historicism would no longer blindly bind artists and craftspersons to antiquated notions of style. Punctuated by the great International Exhibitions in Chicago (1893), Paris (1900), Turin (1902), and St. Louis (1904) and spurred by a rising number of salons and exhibitions across Europe, this series examines the historical and aesthetic developments that transpired in this brief period and highlights an era in which the decorative arts were of international importance and national pride. While many saw this–and indeed continue to see this–as a complete break from the past, the truth is more nuanced and complicated as designers melded their knowledge of history with contemporary forms and ideas in ways that they hoped would speak to the needs of their audiences.

In hindsight, the period resembled a swirling cauldron of often competing ideas that stretched the breadth of the world and culminated in western audiences viewing elements of Japonism, historicism, primitivism, modernism, and a rapid dissemination of local and regional elements, sometimes within the same object. Because of the frequency with which these events were held, and the depth with which they were covered on both sides of the Atlantic, this was a remarkably fruitful period for the decorative arts that deserves a closer look. Across all media–from ceramics to furniture to jewelry to glass to bookbinding and graphic design–virtually no one was immune to these developments or could escape their near ubiquitous influence. It was a period of explosive creativity, remarkable technical achievement, and unimagined aesthetic beauty that helped shape the world we live in and influenced the very way we think about design and its influence.

ABOUT THE INSTRUCTOR

Jonathan Clancy is the Director of Collections and Preservation at the Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms. An author, educator, and curator Clancy received his doctorate in art history in 2008 from the Graduate Center. Formerly Director of the MA in American Fine and Decorative Arts program at Sotheby’s, he left in 2017 to form an advisory group. As an independent consultant, he has worked with private clients and institutions on collection management, exhibition planning, label writing and research, and valuation.

Registration is required. Once registered and paid, you will receive an email prior to each session with a link to join.

Do you have a scheduling conflict for the live session? You can still enjoy the program. Register and we’ll send you the recording! All paid attendees will be emailed a private link to the session recording when it is available, typically 4-5 days after the live program.

Missed us? You can also register retroactively. If you register for a session that has passed, you’ll receive access to the recording when it is ready.

Haven’t tried a session yet? Each session is planned as a “stand-alone” lecture, so you can take them all or attend the topics that interest you most.

5 Sessions for $25/ Session

Best Price! All 5 Sessions for $100 (One class free!)

SCHEDULE

| 1 | Sat., May 11, 2024 | Session 1: Chicago 1893, or the Long and Winding Road to a Design Revolution In many ways, the 1893 Columbian Exposition was perfectly positioned to illustrate imminent confrontation between an older sense of historicism and new design trends that were springing up across Europe in the decorative arts. In various fits and starts, these ideas had been simmering across Europe, especially in ceramics, as exposure to the Japanese exhibits at 1867 Exposition took hold and could be processed, developed, and eventually transformed. For French and Danish potters particularly, the Chicago World’s Fair was a kind of validation, a chance for them to demonstrate these new ideas to a broader audience. |  Jean Joseph Marie Carriés, Gourd Vase, ca. 1890. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Jean Joseph Marie Carriés, Gourd Vase, ca. 1890. Metropolitan Museum of Art. |

| 2 | Sat., May 18, 2024 | Session 2: Dissemination and Discovery: How Salons and Journals Changed the World Nothing happens in a vacuum and without a constant means to promote (and reason to produce) these new styles–from Art Nouveau, to Secessionism, to Arts and Crafts and various intermingling–it is unlikely that they would have gained traction and impacted the public perception to the large degree they did. In addition to the large-scale expositions, salons and exhibitions across Europe played a major role in the dissemination of ideas, not only because they brought artists and audiences into direct contact with new ideas, but because publications like The Studio, Dekorativ Kunst, and Art et Décoration regularly covered these affairs. Moreover, advancements in printing technology–especially those that reduced the difficulty and expense of publishing photographs–meant that the speed with which designs could transmit and migrate promoted rapid changes almost instantly. |  Gertraud von Schnellenbühel, candelabrum, 1913. Münchner Stadtmuseum, Germany. Gertraud von Schnellenbühel, candelabrum, 1913. Münchner Stadtmuseum, Germany. |

| 3 | Sat., June 1, 2024 | Session 3: Paris 1900: “A Truly Positive Result of Modern Artistry” Surveying the ceramics at the 1900 Paris Exposition, Dr. Ernst Zimmerman wrote in Kunst und Handwerk that the skill of French ceramists represented “a truly positive result of modern artistry,” a claim which might be well-suited to the fair as a whole. In contrast to the friction between historicism and revolution that marked the Chicago World’s Fair just seven years earlier, the decorative arts at l’Exposition Universelle 1900 were biased markedly towards the progressive. Dominated in large part by the national taste, this was an apotheosis for the Art Nouveau movement that helped cement Siegfried Bing’s reputation as a tastemaker and savvy promoter in France and abroad. The timid steps towards modern aesthetics taken at Chicago were nowhere on display as glass, metalwork, jewelry, furniture, bookbinding, and ceramics representing the most current design trends across Europe were abundantly displayed. |  René Lalique, ‘Peacock’ corsage ornament, ca. 1898-1900. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon, Portugal. René Lalique, ‘Peacock’ corsage ornament, ca. 1898-1900. Calouste Gulbenkian Museum, Lisbon, Portugal. |

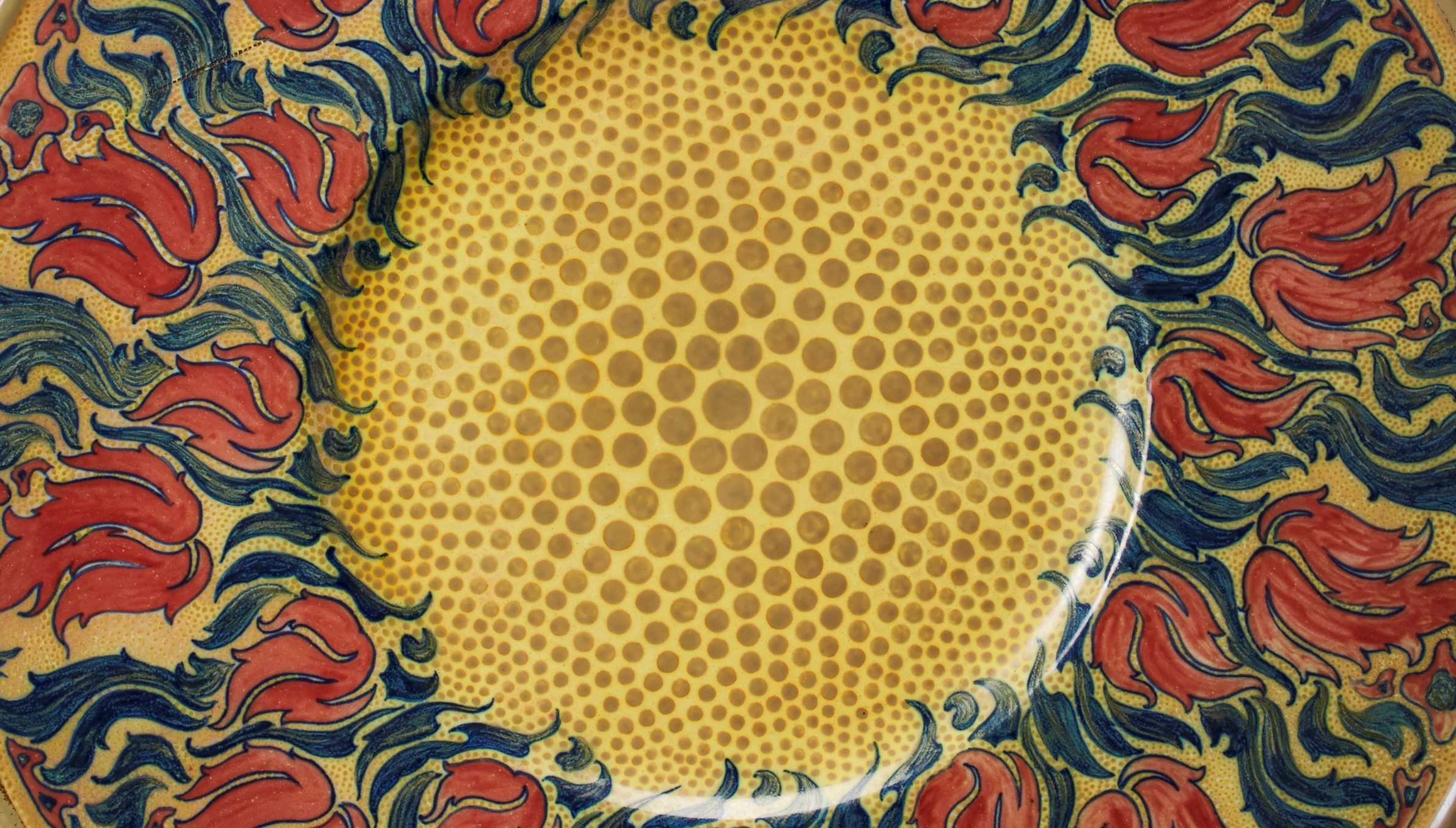

| 4 | Sat., June 8, 2024 | Session 4: Turin 1902: “Traitors to the Grand Traditions” Writing for The Studio about the Turin Exposition in 1902, Dr. Enrico Thovez described “a little band of organizers,” who though accused of “being traitors to the grand traditions which had been bequeathed to them by the decorative art in every country, but above all in Italy” were convinced they could bring a modern sensibility to their countrymen. Though often lost in the gap between Paris in 1900 and the St. Louis World’s Fair in 1904, Turin’s Prima Esposizione Internazionale d’Arte Decorativa Moderna was a celebration of modern design across Europe that this “little band” hoped would spur Italians to look beyond what one critic called “[a] marked tendency towards towards the old Classicism… which is absolutely out of harmony with the aim of modern life” and embrace the present. Led by the work of Carlo Bugatti, L’Arte Della Ceramica, Eugenio Quarti, and Vittorio Ducrot, the Turin Exposition provided a critical mass that helped propel the “Liberty Style” or “Stile Floreale” into the popular consciousness. Particularly strong exhibits by the Dutch, Austrian, and German sections showed a wealth of aesthetics that transcended the label “Art Nouveau” and signaled the breadth of this design revolution throughout Europe. |  Galileo Chini, charger or platter, ca. 1900. Il Ponte, Casa d’Aste,Milan. Galileo Chini, charger or platter, ca. 1900. Il Ponte, Casa d’Aste,Milan. |

| 5 | Sat., June 15, 2024 | Session 5: St. Louis 1904: “…the Paris Exposition of 1900 showed us the Exact Same Thing” Samuel Geijsbeek had a grim assessment of the St. Louis Exposition’s ceramics, which he laid out before the American Ceramic Society and subsequently published. While his claims that there was nothing new (save a transparent matte glaze by Rookwood) and that “The Paris Exposition of 1900 showed us exactly the same thing” could be dismissed as the hyperbole of a crank, hindsight shows us he was on to something. In many ways, the Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis represented the end of an era, a kind of coda to the aesthetic developments that had come forcibly to the front in the 1890s and transformed not only the aesthetics of the moment, but also the regard with which design was held. While strong exhibitions by the German, Danish, and French governments highlighted the current state of design, there was a lingering sense that perhaps this was stagnating. And indeed a shift was coming, by the time of the Brussels Exposition at the end of the decade, major figures like Henry van de Velde and Renee Lalique had begun a shift towards a refined classicism and the journals which had once been so instrumental in reframing the position of the decorative arts took less notice. |  Bernhard Pankok, Germany’s Music Room at The International Exposition in St. Louis 1904. Courtesy of the St. Louis Public Library. Bernhard Pankok, Germany’s Music Room at The International Exposition in St. Louis 1904. Courtesy of the St. Louis Public Library. |

5 Sessions for $25/ Session

Best Price! All 5 Sessions for $100 (One class free!)

MORE INFORMATION

Craftsman Farms, the former home of noted designer Gustav Stickley, is owned by the Township of Parsippany-Troy Hills and is operated by The Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms, Inc., (“SMCF”) (formerly known as The Craftsman Farms Foundation, Inc.). SMCF is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization incorporated in the State of New Jersey. Restoration of the National Historic Landmark, Craftsman Farms, is made possible, in part, by a Save America’s Treasures Grant administered by the National Parks Service, Department of the Interior, and by support from the Morris County Historic Preservation Trust, The New Jersey Historic Trust, and individual donors. SMCF received an operating support grant from the New Jersey Historical Commission, a division of the Department of State and a grant from the New Jersey Arts & Culture Recovery Fund of the Princeton Area Community Foundation. Educational programs are funded, in part, by grants from the Arts & Crafts Research Fund.