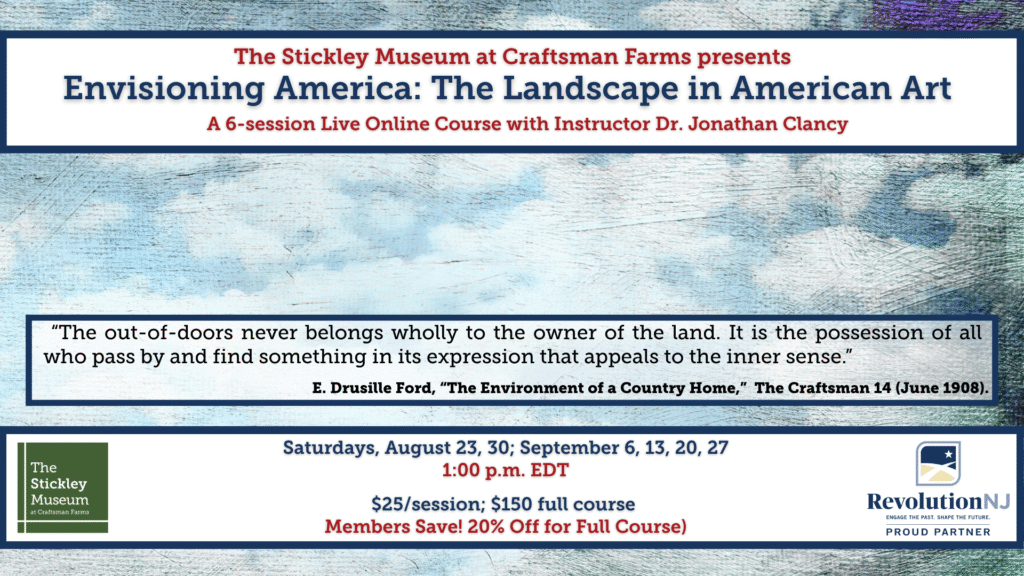

COURSE DESCRIPTION:

“The out-of-doors never belongs wholly to the owner of the land. It is the possession of all who pass by and find something in its expression that appeals to the inner sense.”

E. Drusille Ford, “The Environment of a Country Home,” The Craftsman 14 (June 1908): 287.

The appreciation of–and harmonization with–nature was a fundamental part of the Craftsman movement that is often taken for granted today. Hardly novel, this conception of nature was rooted in approaches to the landscape established by artists since Europeans first arrived on this continent. In this series, we’ll explore the radical reinterpretation of the American Landscape from a menace–something that must be plotted and subdued–into a sanctuary worthy of reverence and protection. By tracking this transformation from the birth of the Early Republic through the eve of World War One we can better appreciate the reverence for nature expressed in the Craftsman Movement.

The brief history of landscape painting we offer in this session is also microcosm of American attitudes, of thought, and of the role of the arts in American society. It is not only about learning to paint differently over time, but at its core is tracking the manner in which Americans learned to see differently over time. We’ll touch upon artists well-known to most–like Sargent, Cassatt, and Whistler–and less familiar names like Willard Metcalf, Robert Duncanson, and Ralph Blakelock. We’ll witness how, throughout history, Americans have returned to the landscape as a source of inspiration, contemplation, and revelation in times of peace and in those of strife.

ABOUT THE INSTRUCTOR

Dr. Jonathan Clancy has been the Director of Collections and Preservation at the Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms since 2020. Those interested in the Arts and Crafts field will know his publications including: The First Metal—Arts & Crafts Copper, These Humbler Metals: Arts and Crafts Metalwork from the Two Red Roses Foundation Collection, Beauty in Common Things: American Arts and Crafts Pottery from the Two Red Roses Foundation as well as articles for The Journal of Modern Craft, Style 1900 and Journal of Design History. Other contributions include chapters and articles on topics ranging from Studio pottery after World War II, American trompe l’oeil paintings of money, and John Singleton Copley’s Watson and the Shark. He is currently co-authoring a catalog on European ceramics for the St. Louis Art Museum and contributing to a planned exhibition on French ceramist Taxile Doat. His article on the ceramic collection of Gustav Stickley for the journal Ceramics in America will appear later this year.

Registration is required. Once registered and paid, you will receive an email prior to each session with a link to join.

Do you have a scheduling conflict for the live session? You can still enjoy the program. Register and we’ll send you the recording! All paid attendees will be emailed a private link to the session recording when it is available, typically 4-5 days after the live program.

Missed us? You can also register retroactively. If you register for a session that has passed, you’ll receive access to the recording when it is ready.

Haven’t tried a session yet? Each session is planned as a “stand-alone” lecture, so you can take them all or attend the topics that interest you most.

6 Sessions for $25/ Session

Member Price! All 6 Sessions for $120 (20% off!)

| 1 | Sat., August 23, 2025 at 1:00 P.M. EDT | Session 1: The Birth of Landscape Art The notion of pure landscape painting–of depicting a scene for its natural beauty and devoid of all historical and religious significance–was somewhat incomprehensible to the cultured classes of the 17th and much of the 18th centuries. And in Colonial America particularly, where a dearth of talented artists and the expense of materials made any painted representation quite dear, the genre is all absent altogether. This session explores the birth of landscape painting in America tracing its rise from a dubious use of canvas to a pursuit worthy of exhibition. Through works of painters like Alvan Fisher, Thomas Doughty, and William Groombridge we’ll explore the visual ways of depicting the land and the cultural forces that helped shape these. By uncovering the ways Americans depicted their environments we’ll trace the development of how the nation learned to see the landscape in new ways. |  William Groombridge, View of a Manor House of the Harlem River, New York, 1793. Terra Foundation for American Art. |

| 2 | Sat., August 30, 2025 at 1:00 P.M. EDT | Session 2: The Hudson River School (and its variants) Building on the successes of painters like Doughty and Fisher, the so-called “Hudson River School” emerged in the 1820s and quickly spread throughout the young nation as the dominant model of Landscape painting. Led by luminary artists like Thomas Cole, Sanford Gifford, and Asher Durand they depicted the “wilds” of the American Northeast through various Romantic lenses ranging from the sublime to the pastoral and sentimental. Gifford, along with Martin Johnson Head and Fitz Henry Lane, pursued a more puzzling and personal vision of the landscape that has been termed “luminist” and is noted for its stillness, subtlety, and quietude. In this session we’ll see how these artists (and their patrons) recognized the importance of what was transpiring and envisioned the development of a uniquely American art. |  Sanford Robinson Gifford, The View from Eagle Rock, New Jersey, 1862. The Amon Carter Museum of American Art. |

| 3 | Sat., September 6, 2025 at 1:00 P.M. EDT | Session 3: Grand Visions Echoing the restlessness and expansionist tendencies of the broader population, American Landscape painters plied their trade further afield–from the West, to the Arctic, to the Tropics of Central and South America–providing a visual counterpart to dry doctrines and concepts like the Monroe Doctrine (1823) and manifest destiny. These images, and the manner in which they were viewed at various times reflected, encouraged, and transformed the broader cultural shifts that were underway. Throughout the rise of artists like Albert Bierstadt to Frederic Church to Thomas Moran we’ll explore the manner in which the Landscape became a vehicle for artistic bravura, cultural ambitions, and personal fame. We’ll look too at how the photographers of the period and the rise of tourism shaped the visual language of the landscape. |  Thomas Moran, Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, 1872. U. S. Department of the Interior. |

| 4 | Sat., September 13, 2025 at 1:00 P.M. EDT | Session 4: American Impressionism Like a pendulum, the history of American Art swings back and forth between the lure of the exotic or foreign and the steady thump of nationalism. It was perhaps inevitable then that following the nationalist rhetoric of the Hudson River School that American artists would once again look abroad for a style that captured the essence of the moment. Here, as they had before, they turned to Paris and the Impressionists. Some, like Mary Cassatt, left and never returned, though her impact on collection building would prove incalculable. Others, like Julian Alden Weir, John Twachtman, and Willard Metcalf remained in the United States and would go on to form The Ten (1898) which became the primary artists’ group for Impressionism to exhibit and expand its reach. |  J. Alden Weir, The High Pasture, 1899-1902. The Phillips Collection. |

| 5 | Sat., September 20, 2025 at 1:00 P.M. EDT | Session 5: Tonalism Developing alongside Impressionists (and in many cases preceding it), were the works of American painters looking to Barbizon, Munich, Italy and England as their source of inspiration. Eschewing the individual strokes and lighter palette that often defined Impressionist works, these artists created works that were brushy, vigorous, and vaporous with a saturation of color frequently missing in their Paris-oriented contemporaries. Through works by artists like George Inness, Charles Warren Eaton, and Albert Pinkham Ryder we’ll explore the rise of the American tonalists and see how this helped lay the foundation for the early modernists’ conception of composition and place. |  George Inness, Early Autumn, Montclair, 1891. Delaware Art Museum. |

| 6 | Sat., September 27, 2025 at 1:00 P.M. EDT | Session 6: Towards a Modern Landscape While Impressionism proved to be a kind of dead end from which further development was stifled, modernists built upon previous developments of Tonalism and Expressionism to advance their engagement with the American Landscape. In these pursuits, some–like Rockwell Kent and Georgia O’Keeffe–were directly aided by Arthur Wesley Dow, while others–like Marsden Hartley and Arthur Dove–fell under the spell and tutelage of gallerist and photographer Alfred Stieglitz. Freed from the constrictions of realism and the painterly abstractions that emerged from the vigorous brushwork of the late 19th century, these early modernists inherited a reverence for the landscape that had emerged in the preceding century but developed new and novel ways to express these ideas. |  Rockwell Kent, Snow Fields (Winter in the Berkshires), 1909. Smithsonian American Art Museum. |

6 Sessions for $25/ Session

Member Price! All 6 Sessions for $120 (20% off!)

MORE INFORMATION

Craftsman Farms, the former home of noted designer Gustav Stickley, is owned by the Township of Parsippany-Troy Hills and is operated by The Stickley Museum at Craftsman Farms, Inc., (“SMCF”) (formerly known as The Craftsman Farms Foundation, Inc.). SMCF is a 501(c)(3) not-for-profit organization incorporated in the State of New Jersey. Restoration of the National Historic Landmark, Craftsman Farms, is made possible, in part, by a Save America’s Treasures Grant administered by the National Parks Service, Department of the Interior, and by support from the Morris County Historic Preservation Trust, The New Jersey Historic Trust, and individual donors. SMCF received an operating support grant from the New Jersey Historical Commission, a division of the Department of State and a grant from the New Jersey Arts & Culture Recovery Fund of the Princeton Area Community Foundation. Educational programs are funded, in part, by grants from the Arts & Crafts Research Fund.